Let’s Get in Touch

Recent Blog Posts

The DADM’s Noticeable Silence: Clarifying the Human Role in the Canadian Government’s Hybrid Decision-Making Systems [Law 432.D – Op-Ed 2]

This is part 2 of a two-part series sharing Op-Eds I wrote for my Law 432.D course titled “Accountable Computer Systems.” This blog will likely go up on the course website in the near future but as I am hoping to speak to and reference things I have written for a presentations coming up, I am sharing here, first. This blog discusses the hot topic of ‘humans in the loop’ for automated decision-making systems [ADM]. As you will see from this Op-Ed, I am quite critical of our current Canadian Government self-regulatory regime’s treatment of this concept.

As a side note, there’s a fantastic new resource called TAG (Tracking Automated Government) that I would suggest those researching this space add to their bookmarks. I found it on X/Twitter through Professor Jennifer Raso’s post. For those that are also more new to the space or coming from it through immigraiton, Jennifer Raso’s research on automated decision-making, particularly in the context of administrative law and frontline decision-makers is exceptional. We are leaning on her research as we develop our own work in the immigration space.

Without further ado, here is the Op-Ed.

The DADM’s Noticeable Silence: Clarifying the Human Role in the Canadian Government’s Hybrid Decision-Making Systems[i]

Who are the humans involved in hybrid automated decision-making (“ADM”)? Are they placed into the system (or loop) to provide justification for the machine’s decisions? Are they there to assume legal liability? Or are they merely there to ensure humans still have a job to do?

Effectively regulating hybrid ADM systems requires an understanding of the various roles played by the humans in the loop and clarity as to the policymaker’s intentions when placing them there. This is the argument made by Rebecca Crootof et al. in their article, “Humans in the Loop” recently published in the Vanderbilt Law Review.[ii]

In this Op-Ed, I discuss the nine roles that humans play in hybrid decision-making loops as identified by Crootof et al. I then turn to my central focus, reviewing Canada’s Directive on Automated Decision-Making (“DADM”)[iii] for its discussion of human intervention and humans in the loop to suggest that Canada’s main Government self-regulatory AI governance tool not only falls short, but supports an approach of silence towards the role of humans in Government ADMs.

What is a Hybrid Decision-Making System? What is a Human in the Loop?

A hybrid decision-making system is one where machine and human actors interact to render a decision.[iv]

The oft-used regulatory definition of humans in the loop is “an individual who is involved in a single, particular decision made in conjunction with an algorithm.[v] Hybrid systems are purportedly differentiable from “human off the loop” systems, where the processes are entirely automated and humans have no ability to intervene in the decision.[vi]

Crootof et al. challenges the regulatory definition and understanding, labelling it as misleading as its “focus on individual decision-making obscures the role of humans everywhere in ADMs.”[vii] They suggest instead that machines themselves cannot exist or operate independent from humans and therefore that regulators must take a broader definition and framework for what constitutes a system’s tasks.[viii] Their definition concludes that each human in the loop, embedded in an organization, constitutes a “human in the loop of complex socio-technical systems for regulators to target.”[ix]

In discussing the law of the loop, Crootof et al. expresses the numerous ways in which the law requires, encourages, discourages, and even prohibits humans in the loop. [x]

Crootof et al. then labels the MABA-MABA (Men Are Better At, Machines Are Better At) trap,[xi] a common policymaker position that erroneously assumes the best of both worlds in the division of roles between humans and machines, without consideration how they can also amplify each other’s weaknesses.[xii] Crootof et al. finds that the myopic MABA-MABA “obscures the larger, more important regulatory question animating calls to retain human involvement in decision-making.”

As Crootof et al. summarizes:

“Namely, what do we want humans in the loop to do? If we don’t know what the human is intended to do, it’s impossible to assess whether a human is improving a system’s performance or whether regulation has accomplished its goals by adding a human”[xiii]

Crootof et al.’s Nine Roles for Humans in the Loop and Recommendations for Policymakers

Crootof sets out nine, non-exhaustive but illustrative roles for humans in the loop. These roles are: (1) corrective; (2) resilience; (3) justificatory; (4) dignitary; (5) accountability; (6) Stand-In; (7) Friction; (8) Warm-Body; and (9) Interface.[xiv] For ease of summary, they have been briefly described in a table attached as an appendix to this Op-Ed.

Crootof et al. discusses how these nine roles are not mutually exclusive and indeed humans can play many of them at the same time.[xv]

One of Crootof et al.’s three main recommendations is that policymakers should be intentional and clear about what roles the humans in the loop serve.[xvi] In another recommendation they suggest that the context matters with respect to the role’s complexity, the aims of regulators, and the ability to regulate ADMs only when those complex roles are known.[xvii]

Applying this to the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (as it then was[xviii]) [“EU AI Act”], Crootof et al. is critical of how the Act separates the human roles of providers and users, leaving nobody responsible for the human-machine system as a whole.[xix] Crootof et al. ultimately highlights a core challenge of the EU AI Act and other laws – how to “verify and validate that the human is accomplishing the desired goals” especially in light of the EU AI Act’s vague goals.

Having briefly summarized Crootof et al.’s position, the remainder of this Op-Ed ties together a key Canadian regulatory framework, the DADM’s, silence around this question of the human role that Crootof et al. raises.

The Missing Humans in the Loop in the Directive on Automated Decision-Making and Algorithmic Impact Assessment Process

Directive on Automated Decision-Making

Canada’s DADM and its companion tool, the Algorithmic Impact Assessment (“AIA”), are soft-law[xx] policies aimed at ensuring that “automated decision-making systems are deployed in a manner that reduces risks to clients, federal institutions and Canadian Society and leads to more efficient, accurate, and interpretable decision made pursuant to Canadian law.”[xxi]

One of the areas addressed in both the DADM and AIA is that of human intervention in Canadian Government ADMs. The DADM states:[xxii]

Ensuring human intervention

6.3.11

Ensuring that the automated decision system allows for human intervention, when appropriate, as prescribed in Appendix C.

6.3.12

Obtaining the appropriate level of approvals prior to the production of an automated decision system, as prescribed in Appendix C.

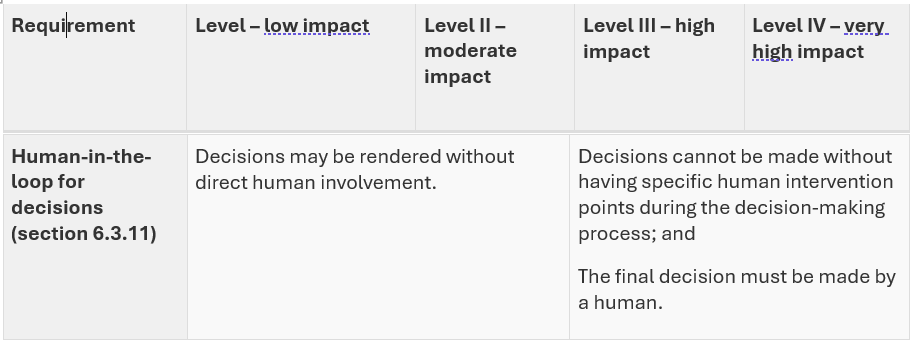

Per Appendix C of the DADM, the requirement for a human in the loop depends on the self-assessed impact level scoring system to the AIA by the agency itself. For level 1 and 2 (low and moderate impact)[xxiii] projects, there is no requirement for a human in the loop, let alone any explanation of the human intervention points (see table below extracted from the DADM).

I would argue that to avoid explaining further about human intervention, which would then engage explaining the role of the humans in making the decision, it is easier for the agency to self-assess (score) a project as one of low to moderate impact. The AIA creates limited barriers nor a non-arms length review mechanism to prevent an agency strategically self-scoring a project below the high impact threshold.[xxiv]

Looking at the published AIAs themselves, this concern of the agency being able to avoid discussing the human in the loop appears to play out in practice.[xxv] Of the fifteen published AIAs, fourteen of them are self-declared as moderate impact with only one declared as little-to-no impact. Yet, these AIAs are situated in high-impact areas such as mental health benefits, access to information, and immigration.[xxvi] Each of the AIAs contain the same standard language terminology that a human in the loop is not required.[xxvii]

In the AIA for the Advanced Analytics Triage of Overseas Temporary Resident Visa Applications, for example, IRCC further rationalizes that “All applications are subject to review by an IRCC officer for admissibility and final decision on the application.”[xxviii] This seems to engage that a human officer plays a corrective role, but this not explicitly spelled out. Indeed, it is open to contestation from critics who see the Officer role as more as a rubber-stamp (dignitary) role subject to the influence of automation bias.[xxix]

Recommendation: Requiring Policymakers to Disclose and Discuss the Role of the Humans in the Loop

While I have fundamental concerns with the DADM itself lacking any regulatory teeth, lacking the input of public stakeholders through a comment and due process challenge period,[xxx] and driven by efficiency interests,[xxxi] I will set aside those concerns for a tangible recommendation for the current DADM and AIA process.[xxxii]

I would suggest that beyond the question around impact, in all cases of hybrid systems where a human will be involved in ADMs, there needs to be a detailed explanation provided by the policymaker of what roles these humans will play. While I am not naïve to the fact that policymakers will not proactively admit to engaging a “warm body” or “stand-in” human in the loop, it at least starts a shared dialogue and puts some onus on the policymaker to both consider proving, but also disproving a particular role that it may be assigning.

The specific recommendation I have is to require as part of an AIA, a detailed human capital/resources plan that requires the Government agency to identify and explain the roles of the humans in the entire ADM lifecycle, from initiation to completion.

This idea also seems consistent with best practices in our key neighbouring jurisdiction, the United States. On 28 March 2024, a U.S. Presidential Memorandum aimed at Federal Agencies titled […]

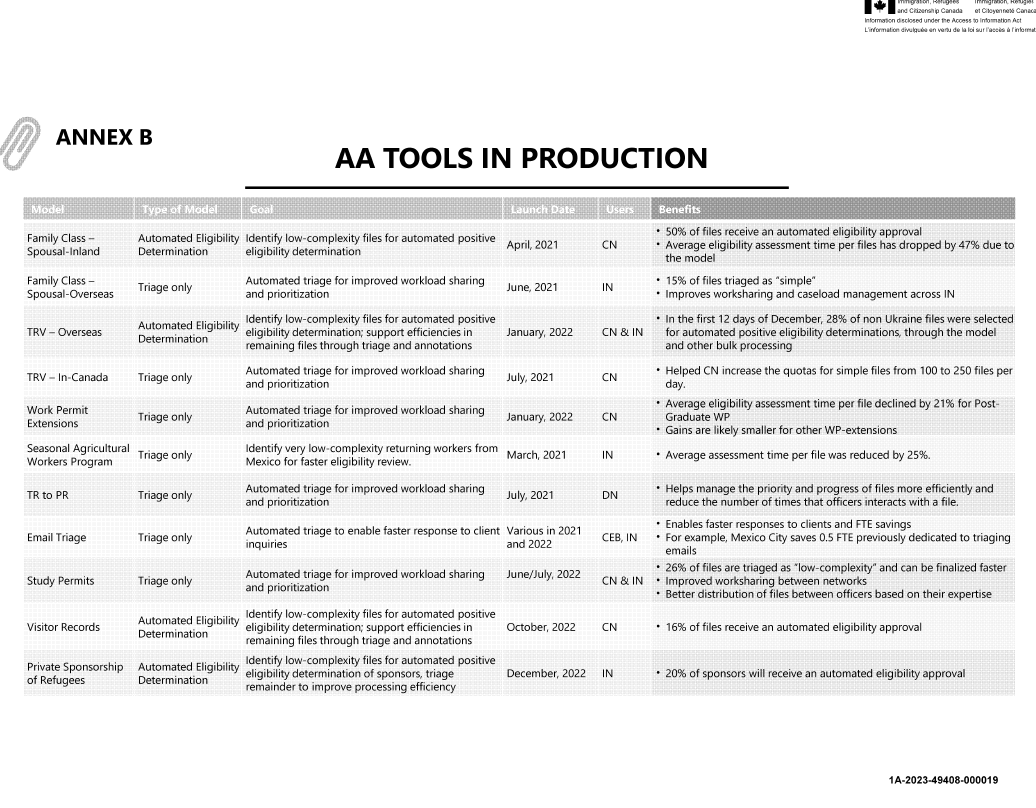

Filling in Three Missing Peer Reviews for IRCC’s Algorithmic Impact Assessments

As a public service, and transparently because I need to also refer to these in my own work in the area, I am sharing three peer reviews that have not yet been published by Immigration, Refugess and Citizenship Canada (“IRCC”) nor made available on the published Algorithmic Impact Assessment (“AIA”) pages from the Treasury Board Secretariat (“TBS”).

First, a recap. Following the 3rd review of the Directive of Automated Decision-Making (“DADM”), and feedback from stakeholders, it was proposed to amend the peer review section to require the completion of a peer review and publication prior to the system’s production.

The previous iteration of the DADM did not require publication nor specify the timeframe for the pper review. The motivation for this was to increase public trust around Automated Decision-Making Systems (“ADM”). As stated in the proposed amendment summary at page 15:

The absence of a mechanism mandating the release of peer reviews (or related information) creates a missed opportunity for bolstering public trust in the use of automated decision systems through an externally sourced expert assessment. Releasing at least a summary of completed peer reviews (given the challenges of exposing sensitive program data, trade secrets, or information about proprietary systems) can strengthen transparency and accountability by enabling stakeholders to validate the information in AIAs. The current requirement is also silent on the timing of peer reviews, creating uncertainty for both departments and reviewers as to whether to complete a review prior to or during system deployment. Unlike audits, reviews are most effective when made available alongside an AIA, prior to the production of a system, so that they can serve their function as an additional layer of assurance. The proposed amendments address these issues by expanding the requirement to mandate publication and specify a timing for reviews. Published peer reviews (or summaries of reviews) would complement documentation on the results of audits or other reviews that the directive requires project leads to disclose as part of the notice requirement (see Appendix C of the directive) (emphasis added)

Based on Section 1 of the DADM, with the 25 April 2024 date coming, we should see more posted peer reviews for past Algorithmic Impact Assessment (“AIA”).

This directive applies to all automated decision systems developed or procured after . However,

- 1.2.1 existing systems developed or procured prior to will have until to fully transition to the requirements in subsections 6.2.3, 6.3.1, 6.3.4, 6.3.5 and 6.3.6 in this directive;

- 1.2.2 new systems developed or procured after will have until to meet the requirements in this directive. (emphasis added)

The impetus behind the grace period, was set out in their proposed amendment summary at page 8:

TBS recognizes the challenge of adapting to new policy requirements while planning or executing projects that would be subject to them. In response, a 6-month ‘grace period’ is proposed to provide departments with time to plan for compliance with the amended directive. For systems that are already in place on the release date, TBS proposes granting departments a full year to comply with new requirements in the directive. Introducing this period would enable departments to plan for the integration of new measures into existing automation systems. This could involve publishing previously completed peer reviews or implementing new data governance measures for input and output data.

During this period, these systems would continue to be subject to the current requirements of the directive. (emphasis added)

The new DADM section states:

Peer review

- 6.3.5 Consulting the appropriate qualified experts to review the automated decision system and publishing the complete review or a plain language summary of the findings prior to the system’s production, as prescribed in Appendix C. (emphasis added)

Appendix C for Level 2 – Moderate Impact Projects (for which all of IRCC’s Eight AIA projects are self-classified) the requirement is as follows:

Consult at least one of the following experts and publish the complete review or a plain language summary of the findings on a Government of Canada website:

Qualified expert from a federal, provincial, territorial or municipal government institution

Qualified members of faculty of a post-secondary institution

Qualified researchers from a relevant non-governmental organization

Contracted third-party vendor with a relevant specialization

A data and automation advisory board specified by Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

OR:

Publish specifications of the automated decision system in a peer-reviewed journal. Where access to the published review is restricted, ensure that a plain language summary of the findings is openly available.

We should be expecting then movement in the next two weeks.

As I wrote about here, IRCC has posted one of their Peer Reviews, this one for the International Experience Canada Work Permit Eligibility Model. I will analyze this (alongside other peer reviews) in a future blog and why I think it is important in the questions it raises about automation bias.

In light of the above, I am sharing three Peer Reviews for IRCC AIAs. These may or may not be the final ones that IRCC eventually posts, presumably before 25 April 2024.

I have posted the document below the corresponding name of the AIA. Please note that the PDF viewer does not work on mobile devices. As such I have also added a link to a shared Google doc for your viewing/downloading ease.

(1) Spouse Or Common-Law in Canada Advanced Analytics [Link]

A-2022-00374_ – Stats Can peer review on Spousal AI Model

Note: We know that IRCC has also been utilizing AA for Family Class Spousal-Overseas but as this is a ‘triage only’ model, it appears IRCC has not published a separate AIA for this.

(2) Advanced Analytics Triage for Overseas Temporary Resident Visa Applications [Link]

NRC Data Centre – 2018 Peer Review from A-2022-70246

Note: there is a good chance this was a preliminary peer review before the current model. The core of the analysis is also in French (which I will break down again, in a further blog)

(3) Integrity Trends Analysis Tool (previously known as Watchtower) [Link]

Pages from A-2022-70246 – Peer Review – AA – Watchtower Peer Review

Note: the ITAT was formerly know as Watchtower, and also Lighthouse. This project has undergone some massive changes in response to peer review and other feedback, so I am not sure if there was a more recent peer review before the ITAT was officially published.

I will share my opinions on these peer reviews in future writing, but I wanted to first put it out there as the contents of these peer reviews will be relevant to work and presentations I am doing over the coming months. Hopefully, IRCC themselves publishes the document so scholars can dialogue on this.

My one takeaway/recommendatoin in this context, is that we should follow what Dillon Reisman, Jason Schultz, Kate Crawford, Meredith Whittaker write in their 2018 report titled: “ALGORITHMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENTS: A PRACTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR PUBLIC AGENCY ACCOUNTABILITY” suggest and allow for meaningful access and a comment period.

If the idea is truly for public trust, my ideal process flow sees an entity (say IRCC) publish a draft AIA with peer review and GBA+ report and allow for the Public (external stakeholders/experts/the Bar etc.) to provide comments BEFORE the system production starts. I have reviewed several emails between TBS and IRCC, for example, and I am not convinced of the vetting process for these projects. Much of the questions that need to be ask require an interdisciplinary subject expertise (particularly in immigration law and policy) that I do not see in the AIA approval process nor peer reviews.

What are your thoughts? I will breakdown the peer reviews in a blog post to come.

Colliding Concepts and an Immigration Case Study: Lessons on Accountability for Canadian Administrative Law from Computer Systems [Op-Ed 1 for Law 432.D Course]

I wrote this Op-Ed for my Law 432.D course titled ‘Accountable Computer Systems.’ This blog will likely be posted on the course website but as I am presenting on a few topics related, I wanted it to be available to the general public in advance. I do note that after writing this blog, my more in-depth literature review uncovered many more administrative lawyers talking about accountability. However, I still believe we need to properly define accountability and can take lessons from Joshua Kroll’s work to do so.

Introduction

Canadian administrative law, through judicial review, examines whether decisions made by Government decision-makers (e.g. government officials, tribunals, and regulators) are reasonable, fair, and lawful.[i]

Administrative law governs the Federal Court’s review of whether an Officer has acted in a reasonable[ii] or procedurally fair[iii] way, for example in the context of Canadian immigration and citizenship law, where an Officer has decided to deny a Jamaican mother’s permanent residence application on humanitarian and compassionate grounds[iv] or strip Canadian citizenship away from a Canadian-born to Russian foreign intelligence operatives charged with espionage in the United States.[v]

Through judicial review and subsequent appellate Court processes, the term accountability has yet to be meaningfully engaged with in Canadian administrative case law.[vi] On the contrary, in computer science accountability is quick becoming a central organizing principle and governance mechanism.[vii] Technical and computer science specialists are designing technological tools based on accountability principles that justify its use and perceived sociolegal impacts.

Accountability will need to be better interrogated within the Canadian administrative law context, especially as Government bodies increasingly render decisions utilizing computer systems (such as AI-driven decision-making systems) [viii] that are becoming subject to judicial review.[ix]

An example of this is the growing litigation around Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s (“IRCC”) use of decision-making systems utilizing machine-learning and advanced analytics.[x]

Legal scholarship is just starting to scratch the surface of exploring administrative and judicial accountability and has done so largely as a reaction to AI systems challenging traditional human decision-making processes. In the Canadian administrative law literature I reviewed, the discussion of accountability has not involved defining the term beyond stating it is a desirable system aim.[xi]

So, how will Canadian courts perform judicial review and engage with a principle (accountability) that it hardly knows?

There are a few takeaways from Joshua Kroll’s 2020 article, “Accountability in Computer Systems” that might be good starting points for this collaboration and conversation.

Defining Accountability – and the Need to Broaden Judicial Review’s Considerations

Kroll defines “accountability” as a “a relationship that involves reporting information to that entity and in exchange receiving praise, disapproval, or consequences when appropriate.”[xii]

Kroll’s definition is important as it goes beyond thinking of accountability only as a check-and-balance oversight and review system,[xiii] but also one that requires mutual reporting in a variety of positive and negative situations. His definition embraces, rather than sidesteps, the role of normative standards and moral responsibility.[xiv]

This contrasts with administrative judicial review, a process that is usually only engaged when an individual or party is subject to a negative Government decision (often a refusal or denial of a benefit or service, or the finding of wrongdoing against an individual).[xv]

As a general principle that is subject to a few exceptions, judicial review limits the Court’s examination to the ‘application’ record that was before the final human officer when rendering their negative decision.[xvi] Therefore, it is a barrier to utilize judicial review to seek clarity from the Government about the underlying data, triaging systems, and biases that may form the context for the record itself.

I argue that Kroll’s definition of accountability provides room for this missing context and extends accountability to the reporting the experiences of groups or individuals who receive the positive benefits of Government decisions when others do not. The Government currently holds this information as private institutional knowledge, with fear that broader disclosure could lead to scrutiny that might expose fault-lines such as discrimination and Charter[xvii] breaches/non-compliance.[xviii]

Consequentially, I do not see accountability’s language fitting perfectly into our currently existing administrative law context, judicial review processes, and legal tests. Indeed, even the process of engaging with accountability’s definition in law and tools for implementation will challenge the starting point of judicial review’s deference and culture of reasons-based justification[xix] as being sufficient to hold Government to account.

Rethinking Transparency in Canadian Administrative Law

Transparency is a cornerstone concept in Canadian administrative law. Like accountability, this term is also not well-defined in operation, beyond the often-repeated phrase of a reasonable decision needing to be “justified, intelligent, and transparent.”[xx] Kroll challenges the equivalency of transparency with accountability. He defines transparency as “the concept that systems and processes should be accessible to those affected either through an understanding of their function, through input into their structure, or both.”[xxi] Kroll argues that transparency is a possible vehicle or instrument for achieving accountability but also one that can be both insufficient and undesirable,[xxii] especially where it can still lead to illegitimate participants or lead actors to alter their behaviour to violate an operative norm.[xxiii]

The shortcomings of transparency as a reviewing criterion in Canadian administrative law are becoming apparent in IRCC’s use of automated decision-making (“ADM”) systems. Judicial reviews to the Federal Court are asking judges to consider the reasonableness, and by extension transparency of decisions made by systems that are non-transparent – such as security screening automation[xxiv] and advanced analytics-based immigration application triaging tools.[xxv]

Consequently, IRCC and the Federal Court have instead defended and deconstructed pro forma template decisions generated by computer systems[xxvi] while ignoring the role of concepts such as bias, itself a concept under-explored and under-theorized in administrative law.[xxvii] Meanwhile, IRCC has denied applicants and Courts access to mechanisms of accountability such as audit trails and the results of the technical and equity experts who are required to review these systems for gender and equity-based bias considerations.[xxviii]

One therefore must ask – even if full technical system transparency were available, would it be desirable for Government decision-makers to be transparent about their ADM systems,[xxix] particularly with outstanding fears of individuals gaming the system,[xxx] or worse yet – perceived external threats to infrastructure or national security in certain applications.[xxxi] Where Baker viscerally exposed an Officer’s discrimination and racism in transparent written text, ADM systems threaten to erase the words from the page and provide only a non-transparent result.

Accountability as Destabilizing Canadian Administrative Law

Adding the language of accountability will be destabilizing for administrative judicial review.

Courts often recant in Federal Court cases that it is “not the role of the Court to make its own determinations of fact, to substitute its view of the evidence or the appropriate outcome, or to reweigh the evidence.”[xxxii] The seeking of accountability may ask Courts to go behind and beyond an administrative decision, to function in ways and to ask questions they may not feel comfortable asking, possibly out of fear of overstepping the legislation’s intent.

A liberal conception of the law seeks and gravitates towards taxonomies, neat boxes, clean definitions, and coherent rules for consistency.[xxxiii] On the contrary, accountability acknowledges the existence of essentially contested concepts[xxxiv] and the layers of interpretation needed to parse out various accountability types,[xxxv] and consensus-building. Adding accountability to administrative law will inevitably make law-making become more complex. It may also suggest that judicial review may not be as effective as an ex-ante tool,[xxxvi] and that a more robust, frontline, regulatory regime may be needed for ADMs.

Conclusion: The Need for Administrative Law to Develop Accountability Airbags

The use of computer systems to render administrative decisions, more specifically the use of AI which Kroll highlights as engaging many types of accountability,[xxxvii] puts accountability and Canadian administrative law on an inevitable collision course. Much like the design of airbags for a vehicle, there needs to be both technical/legal expertise and public education/awareness needed of both what accountability is, and how it works in practice.

It is also becoming clearer that those impacted and engaging legal systems want the same answerability that Kroll speaks to for computer systems, such as ADMs used in Canadian immigration.[xxxviii] As such, multi-disciplinary experts will need to examine computer science concepts and accountable AI terminology such as explainability[xxxix] or interpretability[xl] alongside their administrative law conceptual counterparts, such as intelligibility[xli] and justification.[xlii]

As this op-ed suggests, there are already points of contention, (but also likely underexplored synergies), around the definition of accountability, the role of transparency, and whether the normative or multi-faceted considerations of computer systems are even desirable in Canadian administrative law.

References

[i] Government of Canada, “Definitions” in Canada’s System of Justice. Last Modified: 01 September 2021. Accessible online <https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/ccs-ajc/06.html> See also: Legal Aid Ontario, “Judicial Review” (undated). Accessible online: <https://www.legalaid.on.ca/faq/judicial-review/>

[ii] The Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65 (CanLII), [2019] 4 SCR 653, <https://canlii.ca/t/j46kb> [“Vavilov”] set out the following about reasonableness review:

[15] In conducting a reasonableness review, a court must consider the outcome of the administrative decision in light of its underlying rationale in order to ensure that the decision as a whole is transparent, intelligible and justified. What distinguishes reasonableness review from correctness review is that the court conducting a reasonableness review must focus on the decision the administrative decision maker actually made, including the justification offered for it, and not on the conclusion the court itself would have reached in the administrative decision maker’s place.

[iii]The question for the Court to determine is whether “the procedure was fair having regard to all of the circumstances” and “whether the applicant knew the case to meet and had a full and fair chance to respond”. See: Ahmed v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 72 at […]

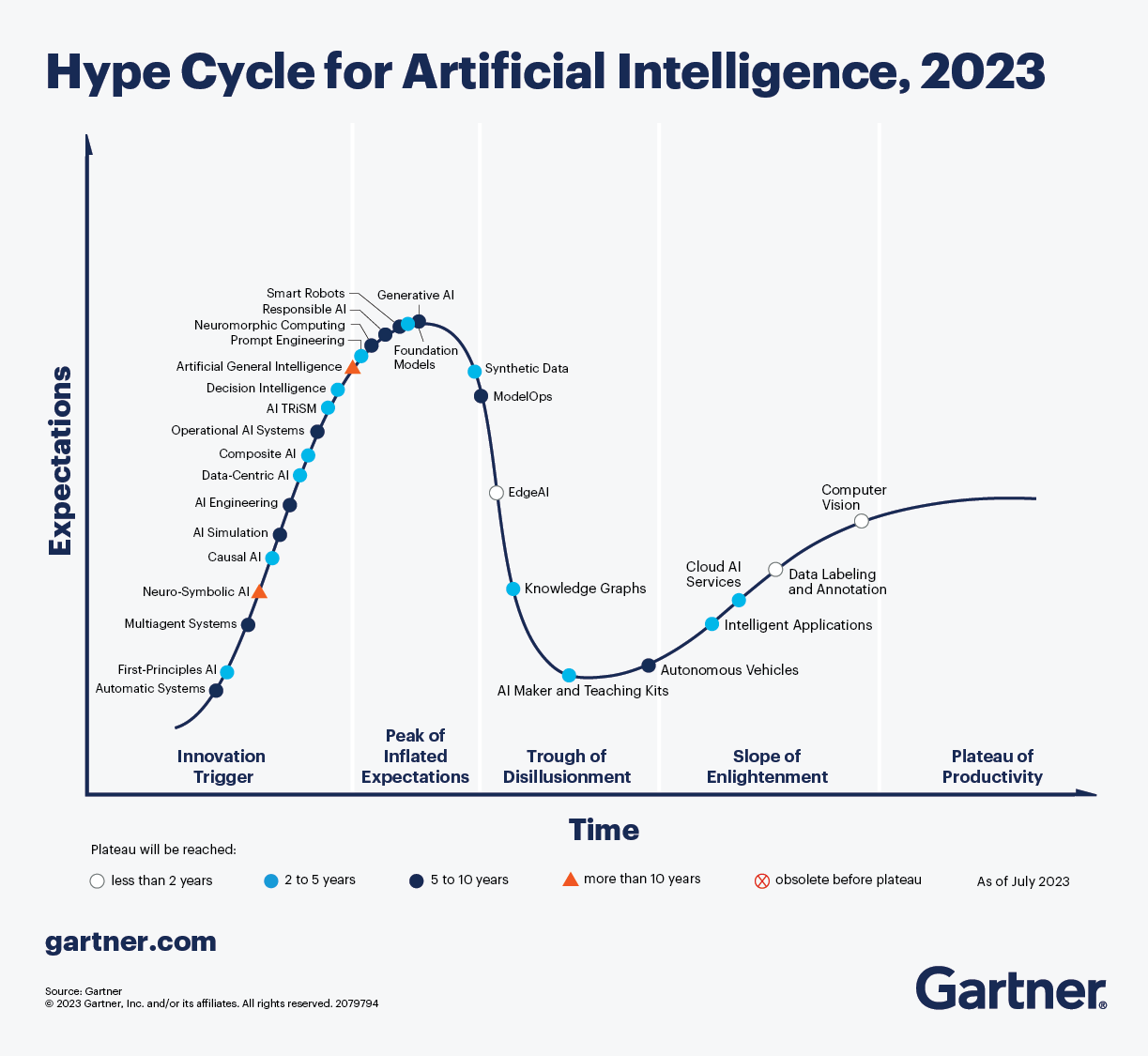

What is an AI Hype Cycle and How Is it Relevant to Canadian Immigration Law?

Recently I have been reading and learning more about AI Hype Cycles.

I first learned this term from Professor Kristen Thomasen when she did a guest lecture for our Legal Methodologies graduate class and discussed it with respect to her own research on drone technology and writing/researching during hype cycles. Since then, in almost AI-related seminar I have attended the term has come up with respect to the current buzz and attention being paid to AI. For example, Timnit Gebru in her talk for the GC Data Conference which I recently attended noted that a lot of what is being repackaged as new AI today was the same work in ‘big data’ that she studied many years back. For my own research, it is important to understand hype cycles to ground my research into more principled and foundational approaches so that I can write and explore the changes in technology while doing slow scholarship notwithstanding changing public discourse and the respective legislative/regulatory changes that might follow.

A good starting point for understanding hype cycles, especially in the AI market, is the Gartner Hype Cycle. Who those who have not heard the term yet, I would recommend checking out the following video:

Gartner reviews technological hype cycles through five phases: (1) innovation trigger; (2) peak of inflated expectations; (3) trough of disillusionment; (4) slope of enlightenment, and plateau of productivity.

It is interesting to see how Gartner has labelled the current cycles:

One of the most surprising things to me on first view is how automatic systems and deicsion intelligence is still on the innovation trigger – early phase on the hype cycle. The other is how many different types of AI technology are on the hype cycle and how many the general public actually know/engage with. I would suggest at most 50% of this list is in the vocabulary and use of even the most educated folks. I also find that from a laypersons perspective (which I consider myself on AI), challenges in classifying whether certain AI concepts fit one category or another or are a hybrid. This means AI societal knowledge is low and even for some of the items that are purportedly on the Slope of Enlightment or Plateau of Productivity.

It is important to note before I move on that that the AI Hype Cycle also has been used in terms outside of the Gartner definition, more in a more criticial sense of technologies that are in a ‘hype’ phase that will eventually ebb and flow. A great article on this and how it affects AI definitions is the piece by Eric Siegel in the Harvard Business Review how the hype around Supervised Machine Learning has been rebranded into a hype around AI and has been spun into this push for Artificial General Intelligence that may or may not be achievable.

Relevance to the Immigration Law Space

The hype cycle is relevant to Canadian immigration law in a variety of ways.

First, on the face, Gartner is a contracting partner of IRCC which means they are probably bringing in the hype cycle into their work and their advice to them.

Second, it brings into question again how much AI-based automated decision-making systems (ADM) is still in the beginning of the hype cycle. It make sense utilizing this framework to understand why these systems are being so heralded by Government in their policy guides and presentation, but also that there could be a peak of inflated expectations on the horizon that may lead to more hybrid decision-making or perhaps a step back from use.

The other question is about whether we are (and I am a primary perpetrator of this) overly-focused on automated-decision making systems without considering the larger AI supply chain that will likely interact. Jennifer Cobbe et al talk about this in their paper “Understanding accountability in algorithmic supply chains” which was assigned for reading in my Accountable Computer Systems course. Not only are there different AI components, providers, downstream/upstream uses, and actors that may be involved in the AI development and application process.

Using immigration as an example, there may be one third-party SAAS that checks photos, another software using black-box AI may engage in facial recognition, and ultimately, internal software that does machine-learning triaging or automation of refusal notes generation. The question of how we hold these systems and their outputs accountable will be important, especially if various components of the system are on different stages of the hype cycle or not disclosed in the final decision to the end user (or immigration applicant).

Third, I think that the idea of hype cycles is very relevant to my many brave colleagues who are investing their time and energy into building their own AI tools or implementing sofware solutions for private sector applicants. The hype cycle may give some guidance as to the innovation they are trying to bring and the timeframe they have to make a splash into the market. Furthermore, immigration (as a dynamic and rapidly changing area of law) and immigrants (as perhaps needing different considerations with respect to technological use, access, or norms) may have their own considerations that may alter Gartner’s timelines.

It will be very interesting to continue to monitor how AI hype cycles drive both private and public innovation in this emerging space of technologies that will significantly impact migrant lives.

Tags

My Value Proposition

My Canadian immigration/refugee legal practice is based on trust, honesty, hard-work, and communication. I don’t work for you. I work with you.

You know your story best, I help frame it and deal with the deeper workings of the system that you may not understand. I hope to educate you as we work together and empower you.

I aim for that moment in every matter, big or small, when a client tells me that I have become like family to them. This is why I do what I do.

I am a social justice advocate and a BIPOC. I stand with brothers and sisters in the LGBTQ2+ and Indigenous communities. I don’t discriminate based on the income-level of my clients – and open my doors to all. I understand the positions of relative privilege I come from and wish to never impose them on you. At the same time, I also come from vulnerability and can relate to your vulnerable experiences.

I am a fierce proponent of diversity and equality. I want to challenge the racist/prejudiced institutions that still underlie our Canadian democracy and still simmer in deep-ceded mistrusts between cultural communities. I want to shatter those barriers for the next generation – our kids.

I come from humble roots, the product of immigrant parents with an immigrant spouse. I know that my birth in this country does not entitle me to anything here. I am a settler on First Nations land. Reconciliation is not something we can stick on our chests but something we need to open our hearts to. It involves acknowledging wrongdoing for the past but an optimistic hope for the future.

I love my job! I get to help people for a living through some of their most difficult and life-altering times. I am grateful for my work and for my every client.

Awards & Recognition

Canadian Bar Association Founders' Award 2020

Best Canadian Law Blog and Commentary 2019

Best New Canadian Law Blog 2015

Best Lawyers Listed 2019-2021

2023 Clawbies Canadian Law Blog Awards Hall of Fame Inductee

Best Canadian Law Blog and Commentary 2021

Canadian Bar Association Founders' Award 2020

Best Canadian Law Blog and Commentary 2019