A Window into the Humanitarian and Compassionate Grounds Judicial Review Outcomes 2018 – 2022

As we posted about in this blog below, we have received a recent data set from IRCC that appears to be first of its kind in tracking litigation at the Federal Court.

An Early “Lens” Into Predicting JR Outcomes by Country of Citizenship

Today I am going to look at Humantiarian and Compassionate Grounds applications specifically and how the outcomes for judicial review have shifted over time since 2018.

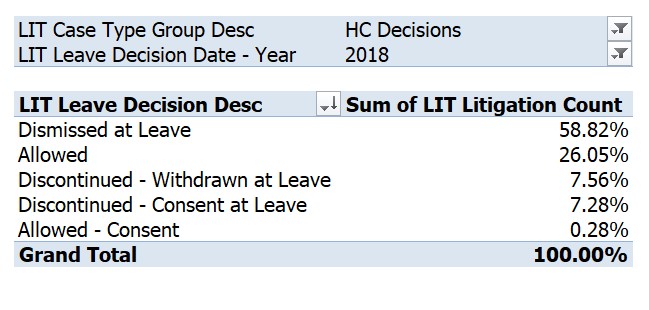

In 2018, there were pretty much two major outcomes – Dismissed at Leave and allowed with both of these outcomes making up nearly 75% of all cases. 14.8% of all decisions ended up in a discontinuance or either consent at leave. The leave dismissal rate was the highest of the five year period at 58.82%.

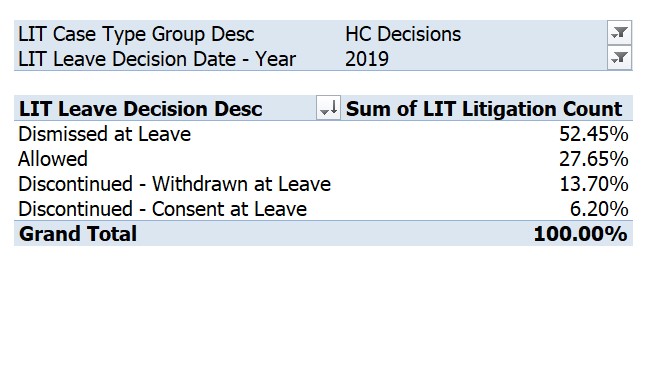

In 2019, we saw similar outcomes with 80% decisions ending up with this outcome and the other 20% ending up in discontinuances. Leave dismissals were still high at 52.45%.

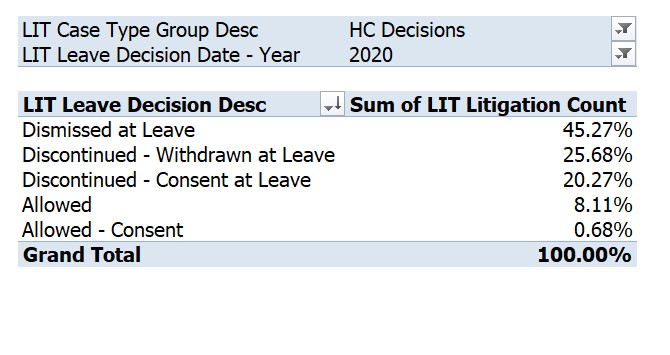

2020’s COVID-19 year saw a major statisical shift. While the rate of leave dismissals went down, so drastically too did the allowed rate. Was this a result of compassion fatigue from COVID itself? or did the discontinuances (including consents) lead to weaker cases being heard by the Court. The motivation to consent or seek discontinuance during COVID-19 could also have been spurred by trying to limit the number of cases requiring hearing. It is a very interesting year to try and study and breakdown especially in light of how a future Global pandemic could impact Court processes.

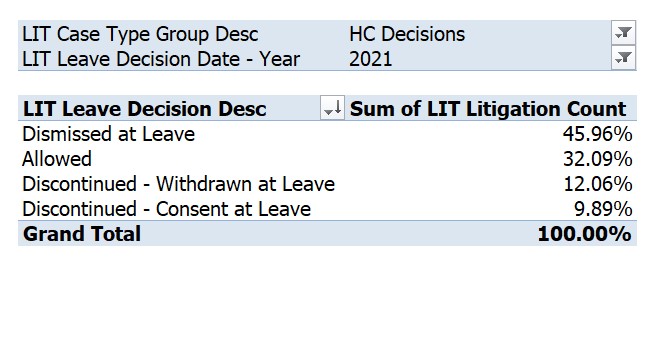

In 2021, the leave dismissal rate stayed consistent around 45.96% but the Allowed rate went back up to higher than pre-pandemic numbers. Discontinued – withdraw and consent rates also went back to pre-pandemic numbers.

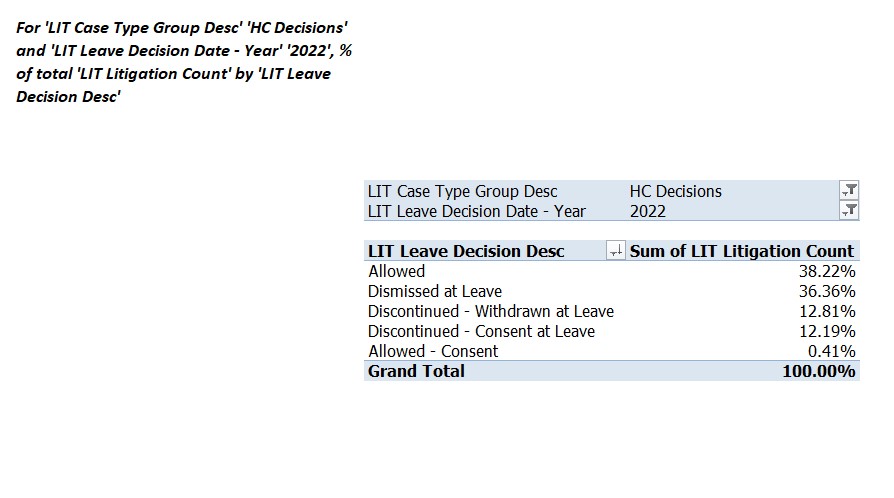

The year 2022 is when it starts getting really interesting. In this year, and for the first year ever, to have a higher percentage of Allowed cases than any other year. If we are looking at pandemic impact, perhaps this year is when many of the Applicants who had stayed in Canada during the 2020-2021 year and made applications finally had their decisions made and challenged at Court.

Dismissal at leave was at a five-year low and the discontinuance rose slightly.

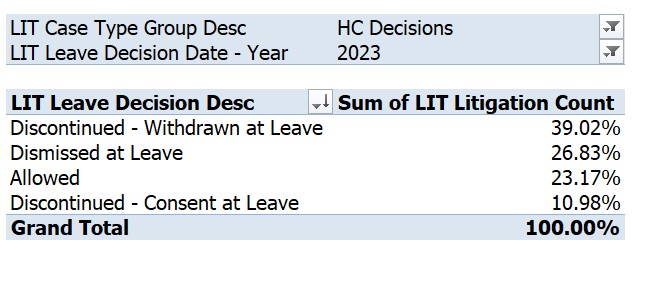

So what happened in 2023. Interestingly enough, another type of outcome – withdrawn at leave – has been number one (up until June 2023 of this year). Are these because folks are no longer interested in pursuing JRs? Are they leaving Canada or are they being removed? These numbers are even higher than in 2020 during the pandemic when travel restrictions were in place. How many of these are from successful reconsideration requests?

This year’s data (to-date) raises several correspondingly interesting issues.

To me, these stats highlight the inconsistencies and ebbs and flows. It further suggests that in terms of automated data-based decision-making, humanitarian and compassionate grounds decisions and judicial reviews probably should not be implemented until greater understanding of why numbers have been discrepant year to year.

What are your thoughts? What stands out with respect to the data for you?

Why the 30-Year Old Florea Presumption Should Be Retired in Face of Automated Decision Making in Canadian Immigration

In the recent Federal Court decision of Hassani v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 734, Justice Gascon writes a paragraph that I thought would be an excellent starting point for a blog. Not only does it capture the state of administrative decision-making in immigration and highlight some of the foundational pieces, but also I want to focus on one part of it that I may respectfully suggest, needs a re-think.

Hassani involved an Iranian international student who was refused a study permit to attend a Professional Photography program at Langara College. She was refused on two factors – [1] that she did not have significant family ties outside Canada and that [2] her purpose of visit was not consistent with a temporary stay given the details she had provided in her application. On the facts, it is definitely questionable that this case even went to hearing given the Applicant had no family ties in Canada and all her family ties were indeed outside Canada and in Iran. Nevertheless, Justice Gascon did a very good job analyzing the flaws within the Officer’s two findings.

There is one paragraph, 26, that is worth breaking down further – and there’s one foundational principle cited that I think needs a major rethink.

Justice Gascon writes:

[26] I do not dispute that a decision maker is generally not required to make an explicit finding on each constituent element of an issue when reaching its final decision. I also accept that a decision maker is presumed to have weighed and considered all the evidence presented to him or her unless the contrary is shown (Florea v Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration), [1993] FCJ No 598 (FCA) (QL) at para 1). I further agree that failure to mention a particular piece of evidence in a decision does not mean that it was ignored and does not constitute an error (Cepeda-Gutierrez v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 1998 CanLII 8667 (FC), [1998] FCJ No 1425 (QL) [Cepeda-Gutierrez] at paras 16–17). Nevertheless, it is also well established that a decision maker should not overlook contradictory evidence. This is particularly true with respect to key elements relied upon by the decision maker to reach its conclusion. When an administrative tribunal is silent on evidence clearly pointing to an opposite conclusion and squarely contradicting its findings of fact, the Court may intervene and infer that the tribunal ignored the contradictory evidence when making its decision (Ozdemir v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2001 FCA 331 at paras 9–10; Cepeda-Gutierrez at para 17). The failure to consider specific evidence must be viewed in context, and it will lead to a decision being overturned when the non-mentioned evidence is critical, contradicts the tribunal’s conclusion and the reviewing court determines that its omission means that the tribunal disregarded the material before it (Penez at paras 24–25). This is precisely the case here with respect to Ms. Hassani’s family ties in Iran. (emphasis added)

What is the Florea Presumption?

As stated by Justice Gascon, the principle in Florea v Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration),[1993] FCJ No 598 (FCA) pertains to a Tribunal’s weighing of evidence and the presumption that they have considered all the evidence before them. It puts the onus on the Applicant stating otherwise, to establish the contrary.

As the Immigration and Refugee Board Legal Services chapter on Weighing Evidence states:

Rather, the panel is presumed on judicial review to have weighed and considered all of the evidence before it, unless the contrary is established. (see: https://irb.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/legal-concepts/Documents/Evid%20Full_e-2020-FINAL.pdf)

This case and principle is often cited in refugee, humanitarian and compassionate grounds matters, inadmissibility cases, and IRB matters.

Reviewing case law for the last two years (since 2021), I did find a handful of the thirty-cases I reviewed that did engage this case and principle in a temporary resident context.

See e.g. study permit JR – Marcelin v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 2021 FC 761 – Madam Justice Roussel at para 16 [JR dismissed]; PNP Work Permit – Shang v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2021 FC 633 at para 65 citing Basanti v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2019 FC 1068 at para 24 – Madam Justice Kane [JR allowed]; Minor Child TRV Refusal – Dardari v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 2021 FC 493 at para 39 – adding the portion – and is not obliged to refer to each piece of evidence submitted by the applicant – Madam Justice St-Louis [JR dismissed];

Related to this is the long-standing and oft-cited decision of Cepeda-Gutierrez v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 1998 FC No 1425 in which Justice Evans re-iterated that an Agency stating they considered all evidence before it (even as a boilerplate statement) would usually be enough to suffice and assure parties and the Court of this. He writes:

[16] On the other hand, the reasons given by administrative agencies are not to be read hypercritically by a court (Medina v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) (1990), 12 Imm. L.R. (2d) 33 (F.C.A.)), nor are agencies required to refer to every piece of evidence that they received that is contrary to their finding, and to explain how they dealt with it (see, for example, Hassan v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) (1992), 147 N.R. 317 (F.C.A.). That would be far too onerous a burden to impose upon administrative decision-makers who may be struggling with a heavy case-load and inadequate resources. A statement by the agency in its reasons for decision that, in making its findings, it considered all the evidence before it, will often suffice to assure the parties, and a reviewing court, that the agency directed itself to the totality of the evidence when making its findings of fact.

(emphasis added)

Why the Florea Presumption Should Be Reversed For Temporary Resident Applications and Any Decision Utilizing Advanced Analytics/AI/Chinook/Cumulus/Harvester

My argument is that this presumption that all evidence has been considered, as well as the boilerplate template language stating that it was considered, should not apply universally in 2023.

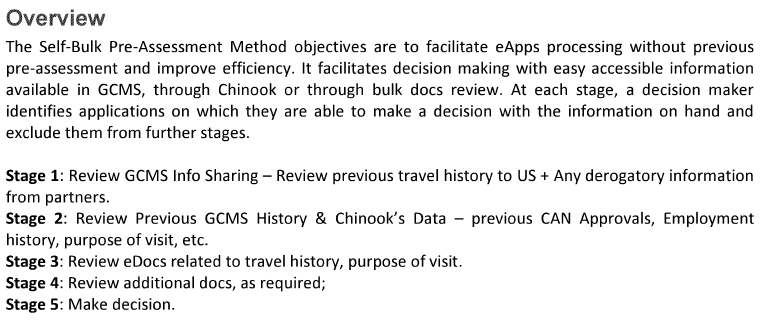

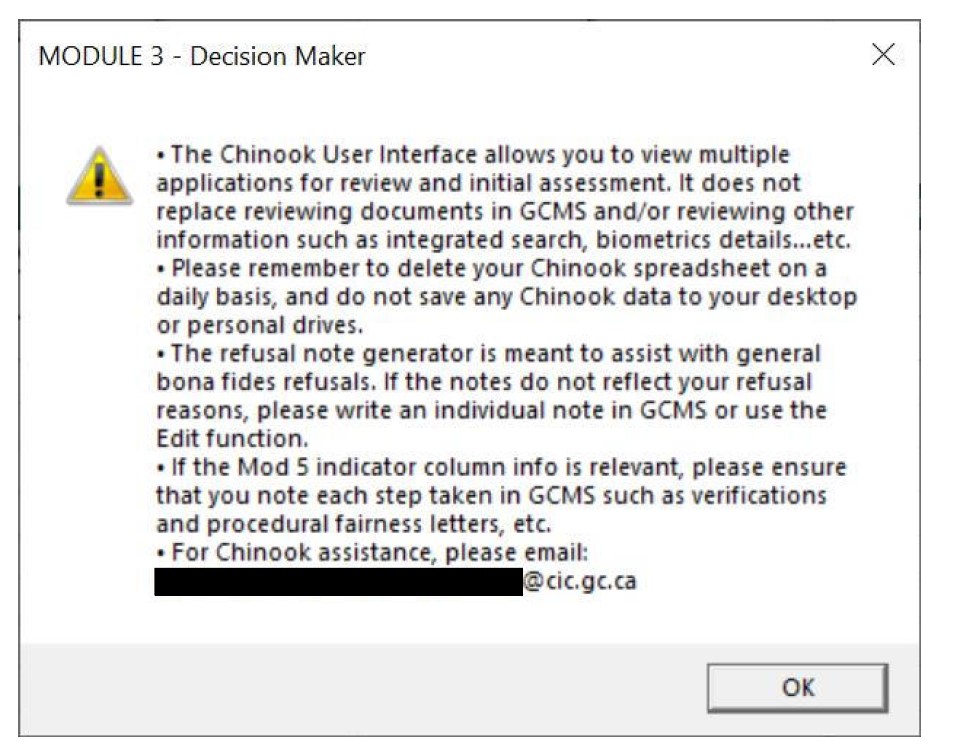

We know enough (again not enough about the system writ large) but enough to know that systems such as Chinook were created to facilitate the processing of temporary resident applications in hundreds of seconds, to extract data into excel tables for bulk processing, and to automate eligibility approvals. These were done specifically allow Officers to spend less time and consider enough, not all, of the evidence before them to render a decision.

I think the fact that applications are being auto-approved for eligibility, simply on a set of rules that are inputted primarily based on biometric information of an applicant should be enough to raise concerns that the systems even require consideration of most of the evidence submitted by an applicant.

All the materials on bulk processing that IRCC has released in the past few years, has been focused on the fact that not all documents need to be reviewed (not wording that states: review Additional Documents, as required).

If you look at the Daponte Affidavit and the original Module 3 Prompt that was created, it does not add confidence to the requirement that all documents needed to necessarily be reviewed:

We learned that in response to concerns, they added to Chinook a prompt reminder for Officers to review all materials, but it is clear Chinook has gone far beyond ‘review and initial assessment’ to bulk processing.

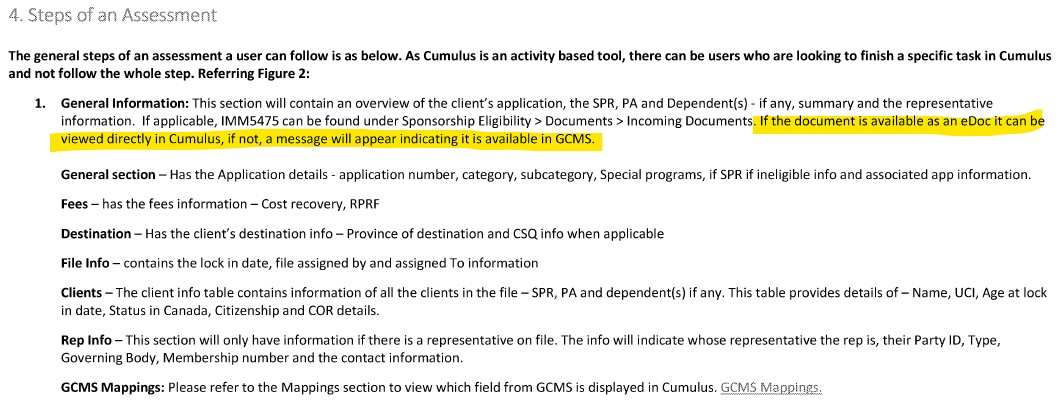

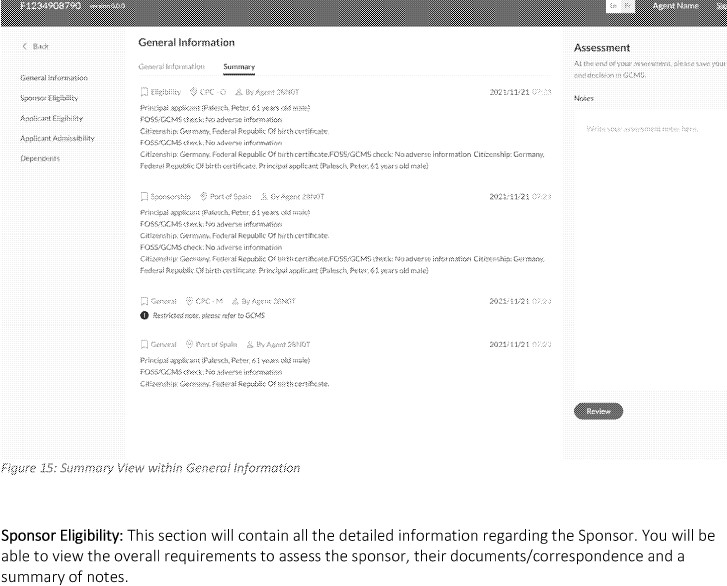

Even with Cumulus, it is clear that if some docs that are not coverted to e-Docs they have to be pulled up separately in GCMS, the very tedious process that tools such as Cumulus seek to avoid.

I would presume that it would be much easier for an Officer to make decision based on these summary extractions then to go into the documents.

The documents are viewed below, much more akin to a ‘preview’ mode.

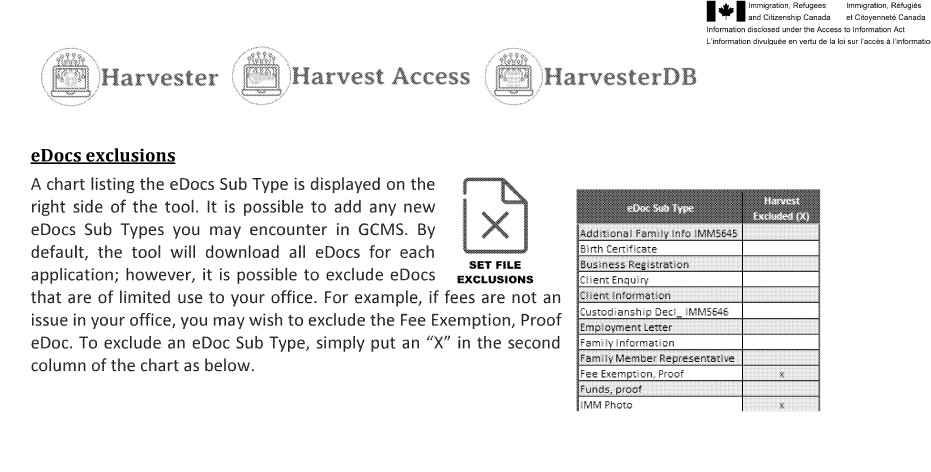

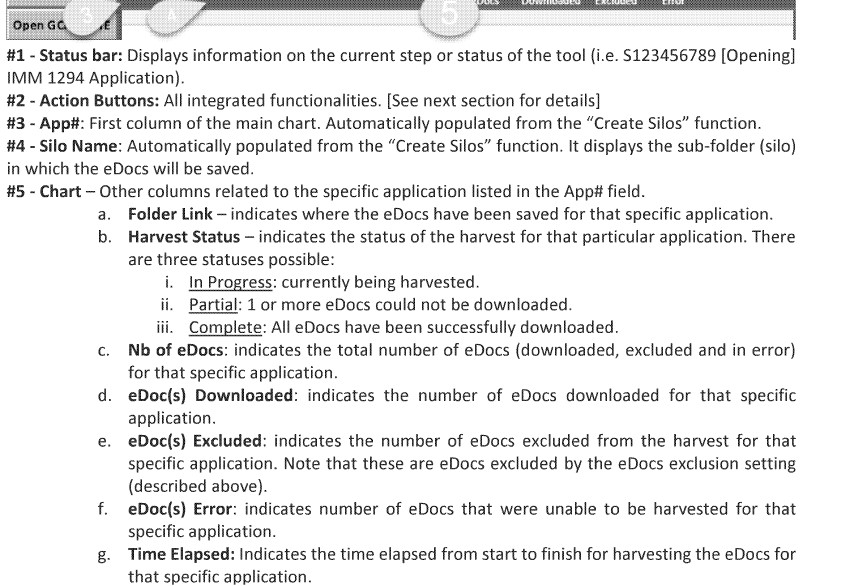

Harvester, a tool that facilitates the conversion of documents into a reviewable format is similarly based on what documents can be extracted.

Based on the way it is described and how some offices can exclude certain documents, it already suggests not all documents make it to the purview of the Officer.

Most importantly, as a constraint is time. As Andrew Koltun has uncovered, IRCC spends 101 seconds on average, with Chinook processing. https://theijf.org/nearly-40-per-cent-of-student-visa-applications-from-india-rejected-for-vague-reasons#

Respectfully, 101 seconds cannot be enough to consider but one or two documents – max – before rendering a decision. The future use […]

Could the Federal Court Have Avoided the Chinook Abuse of Court Process Tetralogy?

What Happened?

In the recent decision of [1] Ardestani v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 2023 FC 874, part of a tetrology of cases where Federal Court justices were critical over attacks on IRCC’s Chinook system, Justice Aylen did not mince words.

She writes:

II. Preliminary Issue

[8] At the commencement of the hearing, counsel for the Applicant advised that he was relying on his written representations but requested that counsel for the Respondent answer five questions related to this matter. As I advised counsel for the Applicant, a hearing of an application for judicial review is not an examination for discovery. Counsel for the Respondent was under no obligation to answer his questions. Moreover, it was not open to the Applicant to raise new issues at the hearing of the application.

[9] I also raised with counsel for the Applicant the fact that two decision of this Court have recently been issued – Raja v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 719 and Haghshenas v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 464 – in which counsel for the Applicant made a number of the same arguments as raised in this application and which were all dismissed by this Court, twice. I asked counsel for the Applicant if he was continuing to pursue these issues notwithstanding the earlier findings of this Court and he indicated that he was.

[10] I find that counsel for the Applicant’s attempt to re-litigate such issues and to transform the hearing of this application into an examination for discovery constitutes an abuse of this Court’s processes. (emphasis added)

In the decision, Justie Aylen comments about the arguments made by applicant against Chinook:

[26] The Applicant asserts that his work permit application was processed using Chinook, which in and of itself is a breach of procedural fairness. Moreover, he asserts that the use of Chinook was improper given the importance of the decision at issue and the degree of complexity of the decision at issue (which involved business immigration). There is also no merit to these assertions. I am not satisfied that the use of Chinook, on its own, constitutes a breach of procedural fairness or that the nature of the application itself has any bearing on the use of Chinook. The evidence before the Court is that the decision was made by an Officer, with the assistance of Chinook. Whether or not there has been a breach of procedural fairness will turn on the particular facts of the case, with reference to the procedure that was followed and the reasons for decision [see Haghshenas, supra].

….

[34] The Applicant further asserts that the use of Chinook is

“concerning”, suggesting essentially that any decision rendered in which Chinook was used cannot be reasonable. I see no merit to this suggestion. The burden rests on the Applicant to demonstrate that the decision itself lacks transparency, intelligibility and/or justification, and baseless musings about how Chinook was developed and operates does not, on its own, meet that threshold. (emphasis added)

While Justice Aylen discusses two other cases Raja and Hagshenas, there was also a third that was released just before Ardestani, in Zargar. All of these cases involve essentially an identical fact pattern of Iranian C11 applicants being refused work permits.

For the interests of summarizing the discuss of Chinook on each, and notwithstanding that I have only seen the full file record in Hagshenas (and have also written a past post, see: here), I will extract block quotes of what judges have said in each of the remaining three decisions about Chinook.

[2] Zargar v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 905 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/jxxpc> – Justice McDonald, Dismissed

[12] Firstly, the allegations regarding: (a) the use of Chinook, (b) reasons only being provided after the judicial review Application was filed, and (c) the length of the processing time were fully canvassed in both Haghshenas v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 464 [Haghshenas] and Raja v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 719 [Raja]. In the absence of any specific evidence to support these allegations in this case, I adopt the analysis from those cases (Haghshenas paras 22-25, 28; Raja at paras 28-38) and can likewise conclude that the Applicant has not established any breach of procedural fairness on these grounds. (emphasis added)

Note that there was an apparent lack of evidence filed in Zargar.

[3] Raja v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 719 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/jxfdq> – Justice Ahmed, Dismissed

[24] The Applicant submits that the Officer assessed his work permit application on the basis of irrelevant and extraneous criteria, but does not specify which criteria. The Applicant also submits that the IRCC’s reliance on Chinook, an efficiency-enhancing tool used to organize information related to applicants for temporary residence, undermines the reasonableness of the Officer’s decision.

….

B. Procedural Fairness

(1) Use of Chinook Processing Tool

[28] The Applicant submits that the Officer’s use of the Chinook processing tool to assist in the assessment of the application is procedurally unfair. The Applicant contends that the tool, which he claims is able to extract information from the GCMS for many applications at a time and generate notes about these applications in

“a fraction of the time”it would take to review an application otherwise, results in a lack of adequate assessment of the Applicant’s work permit application.[29] The Respondent submits that IRCC’s use of the Chinook tool to improve efficiency in addressing a voluminous number of temporary residence applications does not amount to a specific failure of procedural fairness in the Applicant’s case. The Respondent notes that the Applicant has failed to point to any evidence to support that the Officer’s use of the Chinook tool resulted in the omission of a key consideration in the assessment of his application or deprived him of the right to have his case heard. The Respondent contends that the Applicant’s submissions appear to be little more than an objection to IRCC’s use of this tool.

[30] I agree with the Respondent. While it was open to the Applicant to raise the ways that the Chinook processing tool specifically resulted in a breach of procedural fairness in the Officer’s assessment of his case, he has not provided any evidence of such a connection. I would also note that the Chinook tool is not intended to process, assess evidence, or make decisions on applications, and the Applicant has failed to raise any evidence countering this or demonstrating that the tool impacts the fairness of the decision-making process. (emphasis added)

Note – again there appears to be a lack of evidence filed. However I do take issues with the “Chinook tool is not intended to process, assess evidence’ portion. I think there is not enough on the record or in what IRCC has publicly shared to make that statement. It is a processing tool at the end of the day, so a processing tool does process and based on what we know about the modules work (especially Module 5’s risk indicators and local word flags) that it definitely assesses and ‘flags’ the evidence at the very least.

[4]Haghshenas v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 464 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/jwhkd> – Justice Brown, Dismissed

[24] As to artificial intelligence, the Applicant submits the Decision is based on artificial intelligence generated by Microsoft in the form of

“Chinook”software. However, the evidence is that the Decision was made by a Visa Officer and not by software. I agree the Decision had input assembled by artificial intelligence, but it seems to me the Court on judicial review is to look at the record and the Decision and determine its reasonableness in accordance with Vavilov. Whether a decision is reasonable or unreasonable will determine if it is upheld or set aside, whether or not artificial intelligence was used. To hold otherwise would elevate process over substance. (emphasis added)….

[28] Regarding the use of the

“Chinook”software, the Applicant suggests that there are questions about its reliability and efficacy. In this way, the Applicant suggests that a decision rendered using Chinook cannot be termed reasonable until it is elaborated to all stakeholders how machine learning has replaced human input and how it affects application outcomes. I have already dealt with this argument under procedural fairness, and found the use of artificial intelligence is irrelevant given that (a) an Officer made the Decision in question, and that (b) judicial review deals with the procedural fairness and or reasonableness of the Decision as required by Vavilov. (emphasis added)

What arises from the above is precious court resources were spent on four identical cases from the same counsel, making identical arguments, rendering nearly identical judgments all on summating ‘we do not have enough in front of us.’

One wonders if the Department of Justice should have just heeded Justice Little’s comments in Ocran v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2022 FC 175 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/jmk0l> to ask for a reference but as these tools are constantly evolving, I do understand the trepidation and costs:

V. Matters Raised by the Respondent

[57] The respondent raised additional matters for resolution by this Court about the preparation of GCMS notes generally by visa officers using spreadsheets made with a software-based tool known as the

“Chinook Tool”. The respondent sought to resolve an issue about whether contents of Certified Tribunal Record (“CTRs”) were deficient because the spreadsheets are not retained and therefore do not appear in the CTRs prepared for matters such as this application. The respondent also purported to file an affidavit in an effort to provide a factual foundation; the applicant objected to its admissibility and relevance to the proceeding.[58] In my view, the Court should not resolve the additional matters raised by the respondent on this application. There is no dispute or controversy between these […]

The Problem with Khaleel: Extrinsic Evidence Versus Applying Local Knowledge

In this post, I am going to do a gentle critique of a Federal Court decision from last year Khaleel v. Canada (MCI) 2022 FC 1385 and highlight the case as an example of the Court showing too much deference to an Officer’s application of local knowledge, without scrutinizing the reasonableness of the evidentary foundation.

Khaleel

In Khaleel, a Pakistan citizen and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) temporary resident was refused a temporary resident visa (TRV). Khaleel had a long (and largely negative) immigration history in Canada prior to this TRV refusal, but had applied for a business visa to visit Quesnel, B.C. as part of a required exploratory visit.

The key in this decision is Madam Justice Elliot’s upholding of the refusal, on the Officer’s analysis of Saudization. Madam Justice Elliot upheld the reasonableness of IRCC’s analysis that the Applicant’s future employment prospects were negatively impacted by Saudization. The Applicant served as a sales manager for a bakery in KSA and disclosed this as part of his TRV application.

The Officer writes in the GCMS notes for the refusal (reproduced at para 22 of the decision):

Considering the current economic reforms in KSA (Saudization), PA’s occupation (sales manager) is subject to plans for Saudization reforms. I am not satisfied that PA has strong future employment prospects in KSA. The saudization reforms are ongoing and due to the COVID-19 pandemic, reduction in the foreign workforce and layoffs are fast-tracking.

Khaleel argued that the Officer ignored his evidence, including a letter from their employer in Saudi Arabia speaking to the fact that the position was not impacted by COVID and indeed the business remained opened and demand increased.

Madam Justice Elliot writes:

[27] While the employer spoke to the increase in business they have experienced, the Officer is concerned with the national push to reduce foreign workers in KSA.

[29] Regardless of the bakery’s success and reliance on the Applicant’s employment, the business like all others in KSA, is equally subject to the government’s policies to prioritize the employment of Saudi nationals. While the Applicant is correct in stating that the employer’s letter was not explicitly cited in the GCMS notes, I find that was reasonable as the letter does not address the Officer’s concerns about the nation-wide Saudization policies targeting foreign workers with temporary status in KSA

….

[32] As before, the Officer’s concern was the Saudization policies targeting foreign workers with temporary status in KSA. The Applicant’s responsibility for operations, in addition to sales, did not need to be discussed specifically in the reasons as it did not alter the fact that he was at risk as a foreign worker in KSA.

(emphasis added)

The Applicant also challenged, as a matter of procedural fairness reviewable on the correctness standard, the use of extrinsic evidence. Madam Justice Elliot reviewed case law for TRVs emphasizing the Officer’s use of general experience and knowledge of local conditions to draw inferences and reach conclusions without necessarily putting any concerns that may arise to the applicant (at para 57, citing Mohammed v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2017 FC 992,). Again, and like many decisions involving visitors, students, and workers (temporary residents), Madam Justice Elliot emphasized the lack of a qualified right to enter Canada and therefore the low procedural fairness owed.

Madam Justice Elliot writes:

[59] The Officer considered the Applicant only had temporary status in KSA. It is entirely reasonable to expect an applicant for a TRV to anticipate concerns of this sort in relation to their likelihood of return at the end of an authorized visit to Canada.

[60] The Officer was not required to notify the Applicant that he would be relying on public sources regarding general country conditions in KSA and conducting his own research: Chandidas v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2013 FC 257 at paras 25, 29-30.

[61] I do not find that the Officer’s reliance on their general experience and knowledge of local conditions in KSA gave rise to a duty of procedural fairness.

Finding Separation Between Reasonable Analysis Based on Local Knowledge and Speculations and Erred-Analysis Based on Undisclosed Extrinsic Evidence

Accepting again the premise that an applicant should be aware that country conditions may be applied (a premise I find problematic – as open-source searches and unpublished/vetted reports and pull up a whole slew of different findings and can often be subject to either partisan politics or propaganda), I think an Applicant should be able to challenge in judicial review the reasonableness of the local knowledge without necessarily having to predict its application. For example, a temporary resident like Khaleel who has been working and travelling between his country of citizenship and residence for many years, working many jobs may not view it as a future concern (on the ground), but global news articles/studies may highlight it a major problem/characteristic/push factor (on a macro-level).

In this case, there are two findings by Madam Justice Elliot that are worth re-examining.

First, Saudization does not apply equally to all individuals (para 29). Open source information makes it clear that it very industry dependent, position dependent, and timing dependent. See e.g. Saudi Arabia: Saudization Requirements Announced for Several Activities and Professions | Fragomen, Del Rey, Bernsen & Loewy LLP

For example, if the Applicant was seeking a short trip to Canada for several weeks but changes would not kick in for another year or two, this could be relevant factor that appears to be missed in the Officer’s analysis.

Second, whether someone is in sales or operations ( para 32) could be relevant as there are different levels for different industries as discussed and there is no discussion in the decision about his Iqama (permit holding) industry. It is also common practice in KSA for permits to be issued for one profession, but applicants to take on jobs in others with the future possibility of switching.

There is a third issue, that I could think of – involving whether or not percentages even mean too much (for example if an industry is going from 10 percent to 25 percent), if ultimately the expansion of hiring writ large of workers would lead to increases in hireability for both foreign and domestic workers. Khaleel was time during the pandemic, but I could see in another context the Applicant providing evidence that the percentage of Saudization itself is not determinative of the number of opportunities.

Of course, Madam Justice Elliot is not tasked in judicial review with stepping in as Officer to re-evaluate the facts or evidence to decide for herself (Valilov at para 83) but I am concerned that blanketly accepting Officer’s ability to do their own research without even citing the source of this research can very easily lead to misinformation – particularly as we head into the age of digital misinformation. Furthermore, as data is increasingly relied upon as the source of data – it could also lead to the shielding of the actual impetus on reasoning (internal statistics) with these boilerplate recitations of an Officer claiming to rely on country conditions. I also feel, at minimum, an Officer should mention – rather than have it implied – where local knowledge and experience has led to a specific finding.

This concern of boilerplate recitations was also expressed by Justice Sadrehashemi in Mundangepfupfu v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2022 FC 1220 who writes:

[18] The personal circumstances of Ms. Mundangepfupfu were not considered. It is not clear how the country conditions set out by the Officer would affect Ms. Mundangepfupfu, given her living conditions and family support that were described in her applications. The Officer failed to meaningfully account for and respond to key issues and evidence raised by the Applicants, as required (Vavilov at paras 127-128). I agree with the Applicants that this kind of boilerplate recitation of country conditions without an application to the personal circumstances of an applicant could provide the basis for refusing every application for temporary resident status made by a citizen of Zimbabwe. This approach is unreasonable. (emphasis)

Mundangepfupfu at para 18.

Is stating that Saudization applies to all applicants who have temporary resident status in KSA akin to boilerplate recitation? Or is it a reasonable application of an Officer’s local knowledge?

Now let’s assume the Officer actually received facts from the applicant proactively – disputing the application of Saudization, but the Officer still suggest that Saudization will limit the future opportunities of an applicant irregardless of the facts – just as a broad application of Saudization.

Justice Roy states in Demyati v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) 2018 FC 701:

[16] A visa officer is certainly entitled to rely on common sense and rationality. As I have said before, we do not check common sense at the door when entering a courtroom. What is not allowed is to make a decision based on intuition or a hunch; if a decision is not sufficiently articulated, it will lack transparency and intelligibility required to meet the test of reasonableness. That, I am afraid, is what we are confronted with here.

…..

[20] What appears to have been the most important factor in the refusal was the fact that the applicant is a Syrian national who has been living outside of Syria for most of his life. The decision-maker seems to have concluded that given the situation in his country of origin, he would not be inclined to go back to his country of nationality if his residence status in the United Arab Emirates were to […]