Three Useful Canadian Immigration Lessons from the New BC PNP Skills Immigration Guide

Introduction

Now a couple weeks old, the BC PNP’s 2016 offerings for its Skills Immigration Programs have drastically changed the way the bulk of nominations for permanent residence occur in the Province of British Columbia.

Taking lessons from Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada (“IRCC”)’s Express Entry program and following the trend of many provinces towards an electronic application management system, BC PNP has also rolled out it’s own electronic points-based system.

This system requires that the Applicant first create a profile demonstrating they meet requirements. They will be awarded an initial score and then based on their score may automatically be eligible for selection depending on their category of application. Those who do not meet the score requirements for guaranteed invitation can stay in the pool for up to a year and may be issued a nomination if the points total goes down to the score they hold.

I won’t go into the finite details of the program. My colleague, Steven Meurrens has written an excellent post introducing the new program offerings and operation. Please see his post here.

What I want to do in this post is read between the lines a bit to see what current legal issues and policy issues we can extract from the BC PNP’s Skills Immigration and Express Entry BC Program Guide. I believe the guide really, and almost accidentally, susses out some major issues currently affecting those pursuing Canadian immigration options through employment.

For those following at home/work here is a copy of the Program Guide for your viewing pleasure here.

A brief note that I will not be making any normative judgments or criticisms about the BC PNP program in this piece. First, I believe it is much too early to critique something that has not yet been fully tested in operation. Second, I am generally a big fan of the overall concept of using technology to speed up, enhance, and organize the immigration process for applicants. I am a big fan of the BC PNP’s dedication and initiative to eliminating processing times and reducing inventory in several of their previously oversubscribed programs.

So without further ado, here we go:

Lesson 1: BC PNP Provides a Great Guide to Job/Career Planning for Potential Permanent Residents

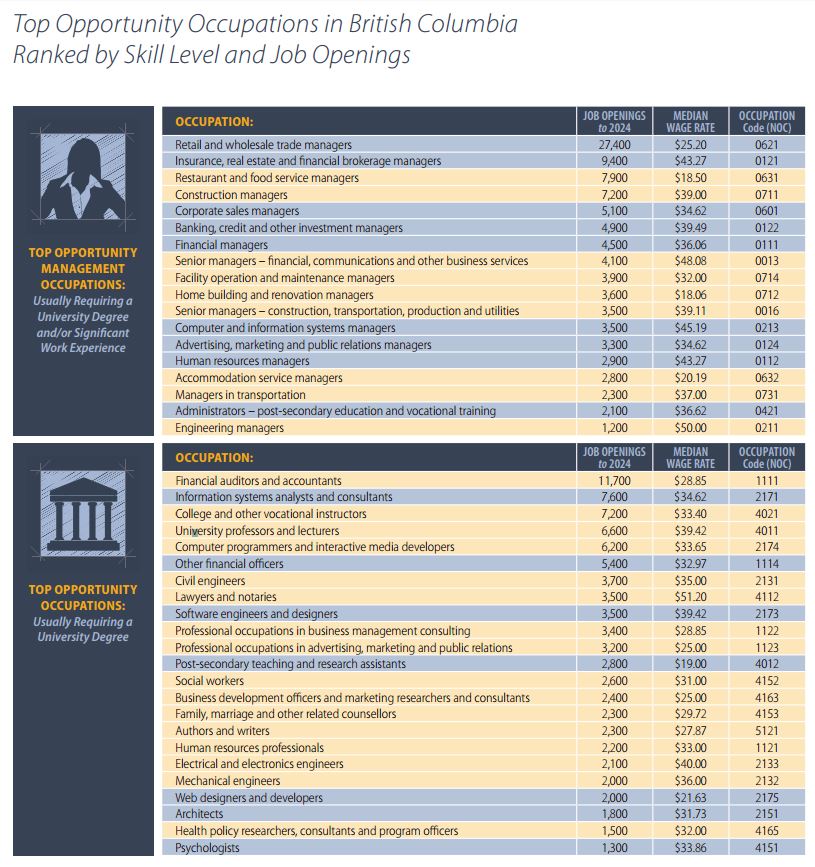

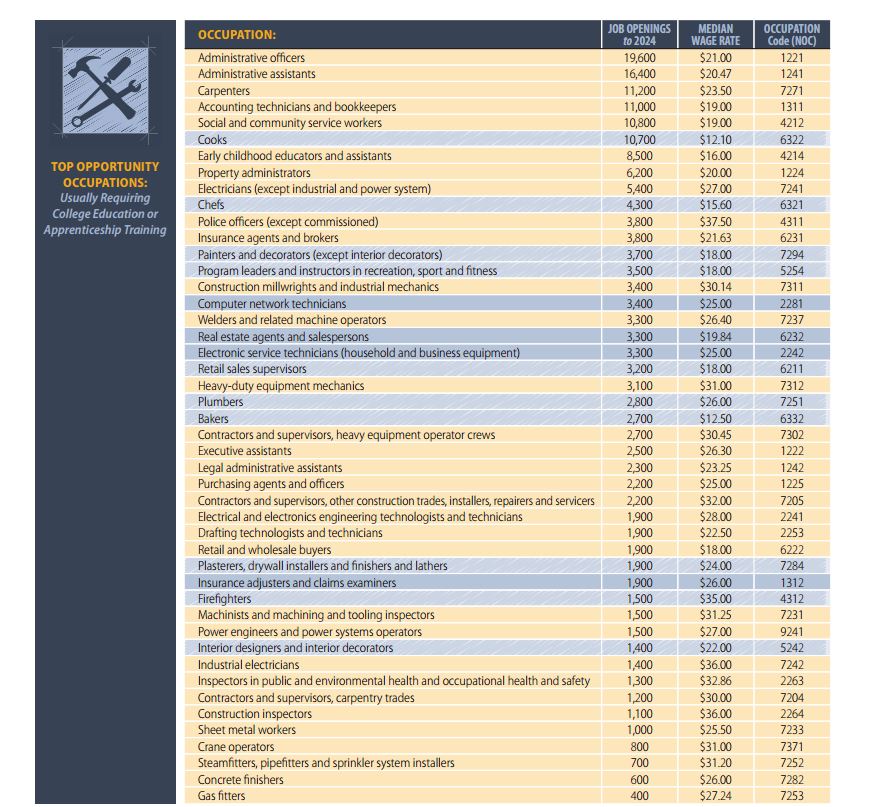

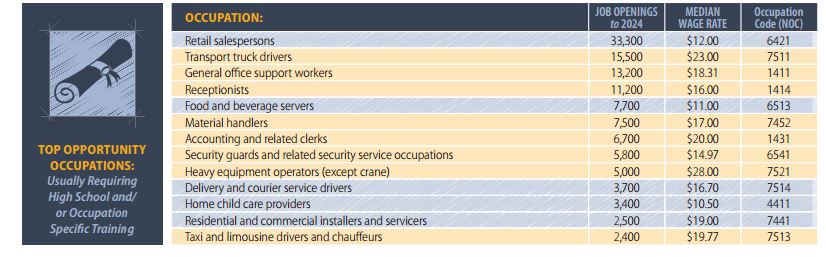

Through the introduction of bonus points, the BC PNP Skills Immigration process awards additional ten (10) points to those working in jobs considered Top 100 in terms of the BC Labour Market Outlook from 2014-2024. You can read the entire report here.

Below are screenshots of the relevant tables. showing the NOC 0, A, B, and C positions.

This guide would be very useful for an international student or a foreign national near graduation from a B.C. high school to look at possible career paths. For each of these occupations, there may be educational requirements as well, so it is important to corresponding look at the National Occupation Classification code (corresponding to the code in the far right columns of the above chart).

Lesson 2: BC PNP Suggests that Tax/Employer/Employee Issues Will Continue to Be Immigration Barriers

a) Permanent Establishment Definition Creates Possible Exceptions to Full-Time Employee Requirement

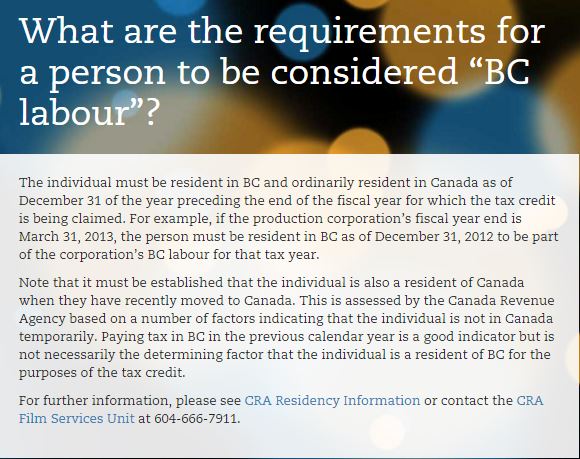

One of the requirements for an employer seeking to use the BC PNP program is that the employer must be “permanently established in B.C. as defined by the federal Income Tax Act.”

There is also a softer requirement that the Employer have at least five indeterminate, full-time employees (or full-time equivalents) if the employer is located within Metro Vancouver or at least three indeterminate, full-time employees (or full-time equivalents) in B.C. if they are located outside Metro Vancouver. However, this is discretionary and BC PNP may take into account a compelling business case if the nomination will generate economic benefit to B.C.

The permanent establishment angle is quite interesting and could give way to unique immigration options. Canada Revenue Agency, interpreting S. 400(1) of the Income Tax Act does not actually require that that the company must have a fixed place of business in the province.

In fact, if the corporation caries on business through an employee or agent it could be considered a permanent establishment if the employee or agent either:

- “has general authority to contract for the corporation;” or

- “has stock of merchandise owned by the corporation from which the employee or agent regularly fills orders received.”

The BC PNP does require that the Employer is:

- incorporated or extra-provincially registered or

- registered as a limited liability partnership in B.C. or

- be an eligible public sector or non-profit employer.

According to the CRA a corporation is deemed to have permanent establishment in B.C., if the place designated in its incorporation documents or bylaw as its head office or registered office is in B.C.

My reading of the above, in addition to the fact there is no parallel requirement that the eligible Employer must be incorporated or must be operational for a certain period of time, is that a new/young start-up company, even unincorporated and without a B.C. operating address, may have options to support a foreign worker’s nomination through BC PNP Skills Immigration.

Given the layer of discretion inherent in the language and BC PNP’s policy, it will be interesting to see how they is used and how BC PNP program officers address this possible pathway to permanent residency.

b) No Contractors and Unexplained Wages

BC PNP establishes several times in the Skills Immigration Guide that only employees qualify for nomination and that independent contractors are not considered indeterminate employees. This could also raise tax issues, as I am aware that recently there has been a hiring practice, particularly in smaller companies/start-ups, to hire what should be employees as contractors instead.

This becomes an issue even prior to creation of the offer of employment to support a potential nomination. BC PNP has also set out in its calculation of the “Minimum Income Requirement” for BC PNP registration that Family Income does not include bonuses, commissions, or profit sharing distributions. Even for those who currently hold valid work permits (many times, post-graduate work permits where there is much flexibility in hiring and wage), applicants must “demonstrate a history of earning the offered wage and a history of meeting minimum income requirements prior to submitting a registration and/or application to the BC PNP. This requirement is even more specific for the Entry level and Semi-Skilled Applicants program – which requires nine full months of evidence (likely through pay stubs).

This will be an important consideration particularly for those applicants who will be relying on international work experience, often times work within a family company, prior to applying to the BC PNP Skills Immigration program. Many times, the arrangements in these companies is very loose, not adequately recorded, and involves some sort of profit/share scenario. Individuals with immigration ambitions through skilled worker programs would be wise to seek legal counsel prior to gaining the requisite work experience used to qualify for BC PNP Skills Immigration.

3. Education, Language (but not Age) are Increasingly Important and Determinative Factors for Permanent Residency

The big change brought in through the new BC Skills Immigration program offerings, independent of the federal requirements already explicit in the Express Entry BC Skills Immigration programs. is that there are now language requirements for NOC B, C, D, positions and that Language now represents 30 out of the 200 possible points on the scoring system for all applicants.

My understanding that for NOC 0 and A occupations, there is no hard requirement to submit language tests but that failure to do so would cost the applicant 30 points. Furthermore, there is an added discretionary risk – both at the pre-nomination level and also at the PR Application level that an Officer (either BC PNP or IRCC) may determine an individual without requisite English skills could not perform the requirements job. Language, for all intents and purposes, is now acting as an important hurdle that several applicants will have to jump.

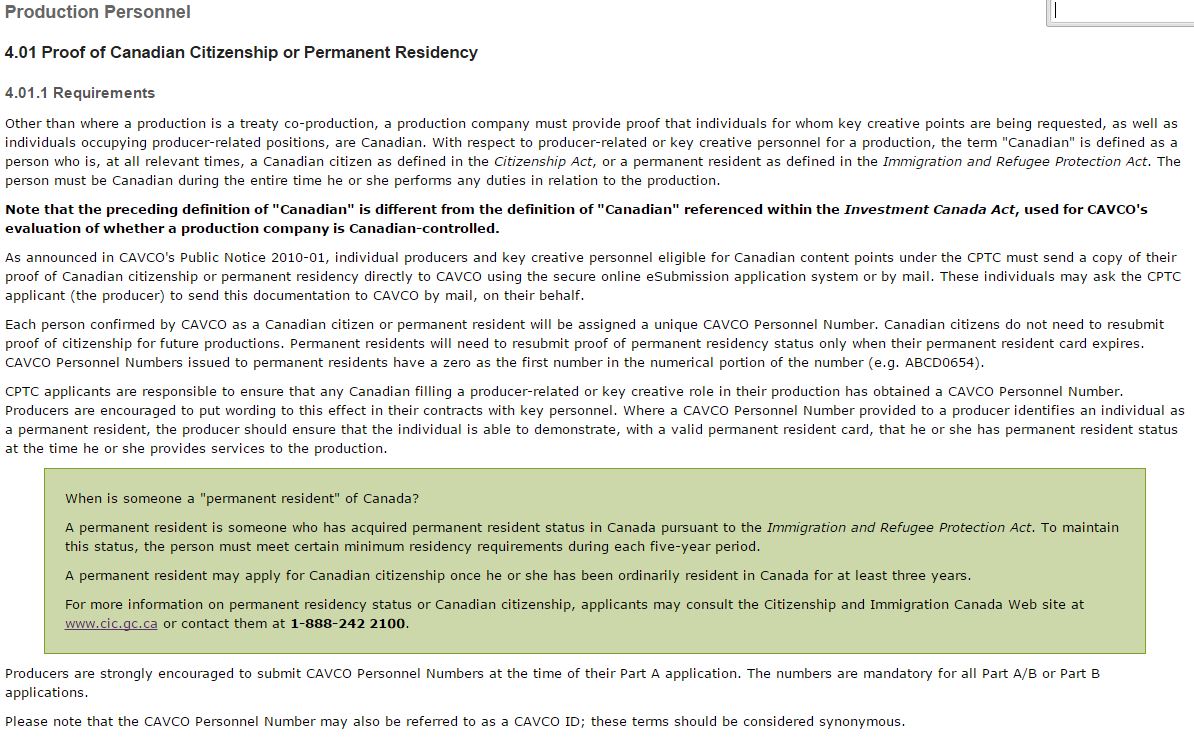

Second, education is becoming scrutinized more carefully. Federally, the government has been implementing several efforts relating to compliance – particularly in the field of individuals who are not actively pursuing studies while holding a study permit (now a ground for removal from Canada).

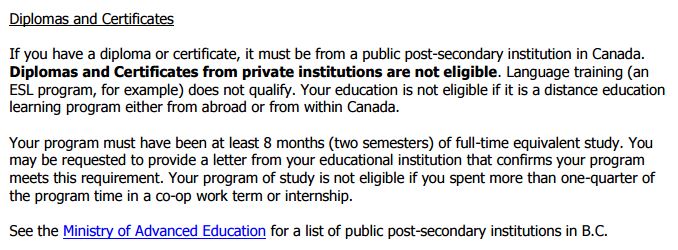

Provincially, you can see the BC PNP suggest that education, particularly diplomas and certificates that qualify one for the International Graduates stream, will be scrutinized more carefully.

They write in their guide:

The bold emphasizes that only public post-secondary institutions support a nomination through the International Graduates program though there are hundred eligible DLIs (mostly private) that support study permits.

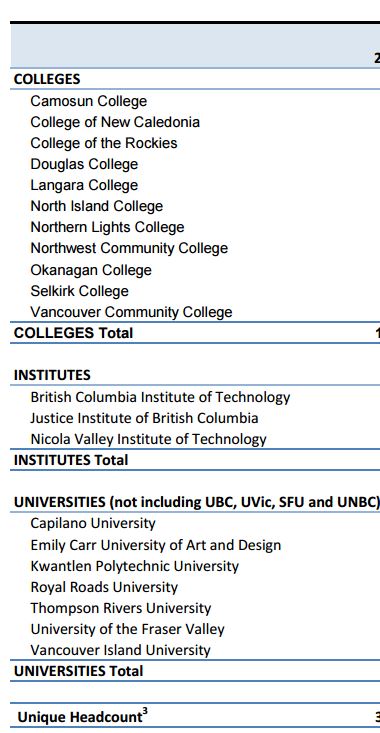

Below are a list of the 21 public post-secondary institutions that could support International Graduates and I would suggest simultaneously would be very popular for students immigrating to Canada with permanent resident ambitions:

(Source: http://www.aved.gov.bc.ca/datawarehouse/documents/headcount.pdf)

Conclusion

The BC PNP Skills Immigration program guide, more than just a document providing information, really represents a window into the challenges and barriers all potential temporary and economic immigrants to Canada are facing. Issues such as hire-ability, employment, tax, language, and education all play a prominent role in the BC PNP Skills Immigration program and will continue to for most provincial and federal economic immigration programs down the road.