IRCC Makes Positive Changes to the Post-Graduate Work Permit Program – February 2019, But First A Little Personal History About Pushing Change

Part 1: First – A Little Personal History about Pushing Change

In advance, I want to make clear that I am not writing this first section to make it appear as if I had anything to do with the changes announced today. This was done by concerned students, stakeholders, schools, other lawyers, and great IRCC policy people engaged in this issue. I am writing this because I’ve been asked by a number of young mentee law students/pre-law students recently (and other fellow junior lawyers) how I got so engaged with international student issues. Rather than just simply copy and paste the website changes, I thought the process of my interest, advocacy, and how it all plays in – may be of interest to some readers.

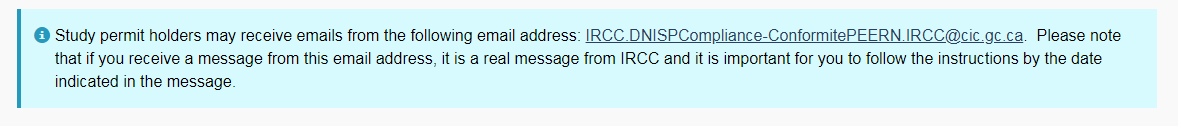

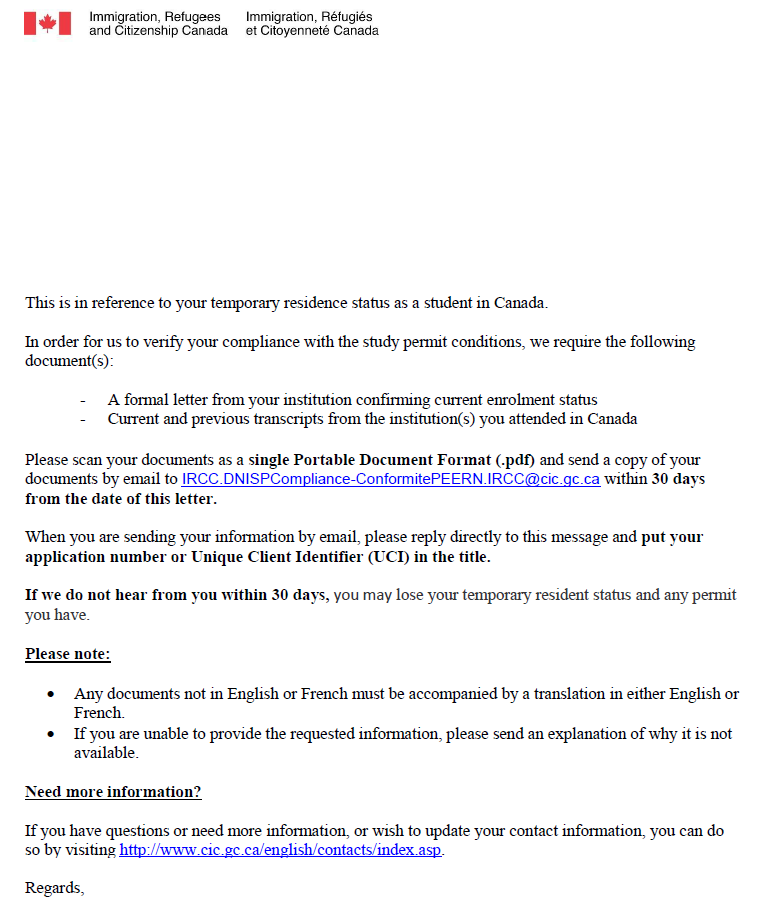

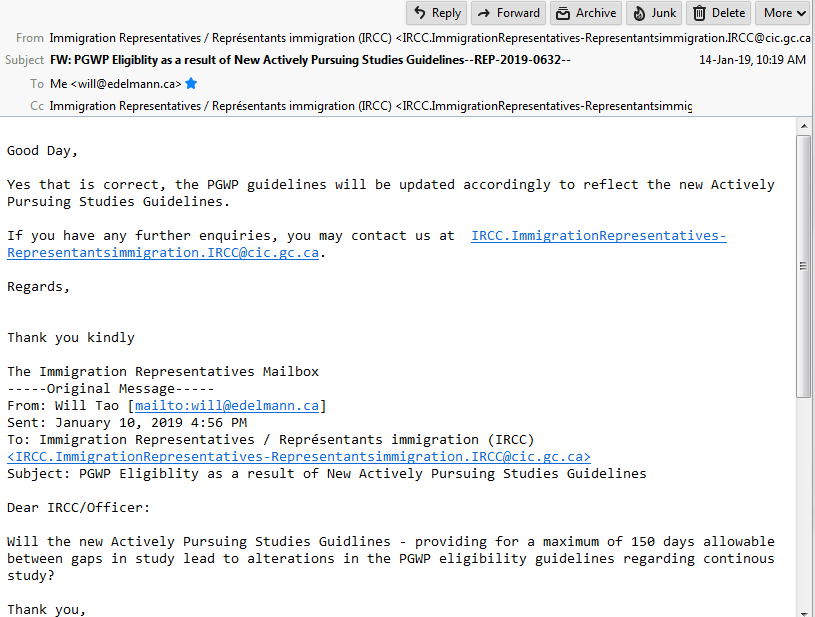

Since IRCC implemented their clarified directive Study Permits: Assessing study permit conditions I had a feeling that new instructions on the PGWP would be coming. A month ago, Immigration Representatives confirmed to me by email that this was the case:

A month later, on Valentine’s Day no less, IRCC placed some little cards into the brown paper bags tied into the back of plastic chairs of international students (sorry – as you can tell I’m getting off topic and nostalgic, as I write) .

As frequent readers of this blog will know, I have been advocating for PGWP changes for several years now, having assisted many clients in various stages of challenges with this program – ranging from eligibility concerns, to initial applications at Inland Offices, VOs, and POEs, to the Federal Court, and reconsideration requests. I gave talks, wrote a lot of articles, had student clients who speoke to media, and advised schools – all because of the uncertainty. At one of my talks I think I described being an international student in Canada as being caught in a rough ocean with a life jacket on and a PR island that often appears too far to swim to.

The past few years began to see a lot of challenges in the area. Refusal rates began to climb and international students, especially from those with non-traditional study programs or for reasons outside of their control had to take leaves in order to complete their studies. While I was successful in restoring several international students who had been refused, either for having their study permits lapse or having paid less than the required fees, the case law during the time (notable FC cases from Raj Sharma and later Ravi Jain), started to close the door on that process.

There was also a huge health toll, one that was lost in the rhetoric of blame placed on international students in mainstream media. I talked a bit about it with journalist, Melanie Green here.

International students, many already dealing with separation anxiety, isolationism, and culture shock, not only pay often times 3 to 4 times the tuition than domestic students, but also face other barriers limiting their ability to work and seek access to crucial settlement services.

From a personal perspective, my own spouse was at the time going through the international student experience as were her colleagues (and I was footing the bill of course!) I saw these issues affect a lot of her friends, especially the financial challenges. Personal experience goes a long way into building a passion for practice.

Looking back, given I was having a conversation about this with IRCC program managers such under three years ago about the need for change – it has indeed been a long time coming. It has been incremental – but now there is a clear list of DLIs on the website, as discussed earlier, the aforementioned actively pursuing studies requirement was clarified, and now this.

I am very proud of IRCC for stepping up for international students. Without further ado, here are the changes.

Part 2: The Changes

IRCC’s changes can be found here and are titled “Program delivery update: Processing Instructions for the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program.”

Wow big changes here! – 6 month period from completion of studies to apply for PGWP and no more requirement to hold a valid SP when applying. Plus others. Will unpack throughout today! #cdnimm #intled https://t.co/uaWF4eRbPb

— Will Tao|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) February 14, 2019

There are two major changes from IRCC and one change that I would also add to the list, around the leave provision.

Change 1: Deadline to Apply Extended from 90 Days to Six Months

There is now a six month period, instead of a 90 day period in which to apply for a Post-Graduate Work Permit. This gives a lot of flexibility for students to further explore after graduation whether they want to continue studying or apply for a post-graduate work permit. It also removes a lot of the uncertainty which arose when a student was told they had completed their studies but did not formally graduate until several months later, creating confusion on the 90 day period starting point. Six months will make that much better.

One of the things I do see arising out of this is change is a lot of schools that were previously thwarted (or had negative fallout) from four-month add on programs now integrating it into their programs. The raison-d’etre is that these programs could assist into entry-to practice and help students secure employment without killing valuable time off their PGWPs. It may also encourage some students to continue studies rather than graduate and apply for PGWPs.

One prediction – if I may so boldly state it is that more schools will tack on four month post-graduate programs given now the 6 month window. PGWP application timing becomes an interesting art in those circumstances. #cdnimm #intled

— Will Tao|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) February 14, 2019

This could create problems though if a student applies at month 4 of 6, makes a mistakes, and becomes ineligible for restoration. Furthermore, I think IRCC and related stakeholders do have a role to play with respect to sussing out that interplay between R.222(1) (a) IRPR which could invalidate the student status of individuals who intend to apply for a PGWP at month 4 or 5 but not continue their studies. These students could lose status unknowingly.

To note – @CitImmCanada & advisors will need to spread awareness – tho students now have longer (6 mo) to apply for PGWPs – 90 days after completion of studies their SPs still statutorily lapse per R. 222(1)(a) IRPR. Could presumably now restore to #PGWP but may be tough. #cdnimm pic.twitter.com/rieEcUx3JX

— Will Tao|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) February 14, 2019

Change 2: No need to hold a valid study permit while applying for a PGWP

This is a big one – which unfortunately came off the backs of several deserving applicants who were refused. Previously, students whose study permits were going to expire before they were able to apply for PGWP had to extend their status, creating a weird scenario where they had graduated but still had to apply to maintain student status at the institution. This also affected a lot of students who decided to leave Canada right after they graduated and apply abroad, forgetting to extend their study permits.

This was also the main issue in my colleague Ravi Jain’s case of Nookala v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2016 FC 1019 which unfortunately for awhile closed the door.

Now the language is hold or held a study permit.

This also opens the door for restoration at least within the six month period. This goes again to the importance of applying earlier (rather than later) for a PGWP in most circumstances.

I would like a little more clarity around Restoration and think it should be a separate section on the program guidelines.

Change 3: Leave Exception – Discretion to Issue PGWP Where Not Continuous Full-Time Studies

IRCC has added to their instructions information about leave which specifically carve out an exception for those students who took a leave.

The Instruction state:

Leave from studies

If the applicant remained in Canada while a student and took leave from their studies during their program, the officer must determine if the applicant was compliant with the conditions of their study permit, as outlined in Assessing study permit conditions. Officers may request additional documents to complete their assessment. Per paragraph R220.1(1)(b), students must

- be enrolled at a DLI

- remain enrolled

- be actively pursuing their course or program of study

If the officer determines that the student actively pursued studies during their leave, the student may still be eligible for the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program (PGWPP).

If it is determined that the student has not met the conditions of their study permit, they may be banned from applying for a post-graduation work permit for 6 months from the date they stopped their unauthorized study or work, per subparagraph R200(3)(e)(i).

This suggests that in addition to leeway – there could also be individuals banned from applying, depending on the time elapsed before graduation. However, as we know there is also a final semester rule that does provide some comfort to international students who are part-time in their final semester.

IRCC’s Guidelines on Leave provide more insight on how this may apply in practice:

D. Leave from studies

Students may be required or may wish to take leave from their studies while in Canada. For the purpose of assessing if a student is actively pursuing their studies, any leave taken from a program of studies in Canada should not exceed 150 days from the date the leave commenced and must be authorized by their DLI.

A student on leave who begins or resumes their studies within 150 days from the date the leave commenced (that is, the date the leave was granted by the institution) is considered to be actively pursuing studies during their leave. If a student does not resume their studies within 150 days, they should do either of the following:

- change their status (that is, change to visitor status or worker status)

- leave Canada

If they […]