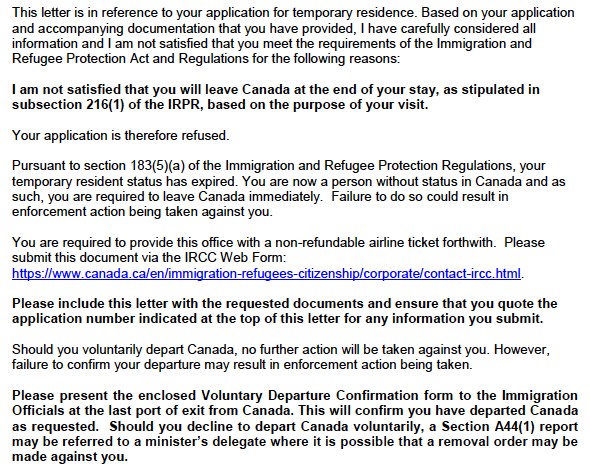

Dear IRCC: Requesting Uploaded Non-Refundable Plane Tickets for Refused Extension Applications Is Not The Way To Go

I apologize folks. I’m in the middle of a transition (starting my own Firm in February – more details about this later). I’ve also engaged an entire revamp of this blog, which will be releasing as well. I’m supposed to be on hiatus. However, something shared by one of my colleagues has had me spring […]

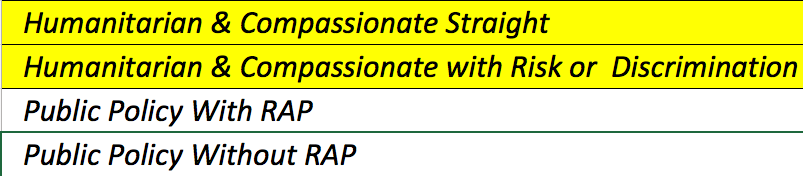

We Straight?: Why Risk and Discrimination May Be The Most Important and Understated H&C Factors

To most individuals, even those familiar with immigration, the words ‘risk’ and ‘discrimination’ will likely conjure up immediate thoughts of refugee claims under s. 96 and s.97 of the IRPA. Indeed, if one were to follow IRCC’s own instructions on factors to consider in an humanitarian and compassionate assessment, risk and determination are not obvious on […]

Indigenous-based Immigration Initiatives in 2020 – What We Hope To Do More of In 2021

Many new readers and fans of our blog ask why we have an Indigenous logo and make Indigenous issues, decolonization, and indigenizing a huge part of our mandate and our writing. We believe that immigration, as part of a settler colonialist system, has facilitate the loss of Indigenous lands, the historically correct approach is to […]

Arenous Updates: Brief to CIMM on Covid-19 and Presentation to Mosaic on International Students

Folks: As many of you may know, over the past half year my colleague Edris Arib and I have been putting together a non-profit organization called the Arenous Foundation to fill the gap of advocacy, research, and education in Canadian immigration. We’ve been doing quite a bit of work this December and are proud to […]

Time to Remedy the Problem of Temporary Resident Permits

co-written w/Yussif Silva, Student Intern, Edelmann and Co. Law Offices Mel is a stateless Palestinian. She grew up stateless in a country that does not offer her Citizenship and no longer offers her status. She has been on successive TRPs but is looking to apply for economic permanent residence and obtain successive work permits. Mel […]

Establishment of a Contradiction: Why Accompanying Dependents Stuck With Covid Study Permit Instructions

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (“IRCC”) has acted quickly and swiftly to adapt to the changing scene for international students as a result of COVID-19. Through changes to program instructions representing the various phases from exclusion (travel bans) to now the accommodation of the Designated Learning Institution (“DLI”) Readiness plans, it is clear that international […]

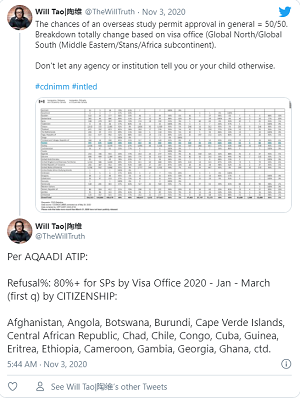

The Under-Examined Role of Racialization in Canadian Immigration

Last week, I presented at the NCIC 2020 on the emerging topic of Critical Race Theory. I wanted to share such a slice of my presentation for further discussion. Vital and pertinent observations from Will Tao and Sharry Aiken during the #NCIC2020 panel