Last week, I presented at the NCIC 2020 on the emerging topic of Critical Race Theory. I wanted to share such a slice of my presentation for further discussion.

Vital and pertinent observations from Will Tao and Sharry Aiken during the #NCIC2020 panel, A Hard Look at How We Practice! pic.twitter.com/ZtM4Ger5Mn

— CAPIC-ACCPI (@capicaccpi) November 20, 2020

Among the five foundational tenets [which include per Delgado and Stefancic: (1) Racism as Ordinary; (2) Interest Convergence; (3) Racialization; (4) Intersectionality and Anti-Essentialism), and (5) Voice-of-Colour (Counternarratives/Legal Storytelling);] one key one is racialization.

Racialization is likely the least understood and (arguably hardest to explain) foundational tenet. It makes some of us who are racialized folks uncomfortable. Those who oppose, find racialization a demeaning term, a short of carved out animal pen of people of colour. Others argue that white folks are ignored when we use the term racialize (a common misconception of the concept) and that such a term ensures a forever uneven playing field with racialized as marginalized and victimized.

When it comes to defining racialization, I would point to the Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre (ACLRC) from Calgary who write:

Racialization is the very complex and contradictory process through which groups come to be designated as being of a particular “race” and on that basis subjected to differential and/or unequal treatment. Put simply, “racialization [is] the process of manufacturing and utilizing the notion of race in any capacity” (Dalal, 2002, p. 27). While white people are also racialized, this process is often rendered invisible or normative to those designated as white. As a result, white people may not see themselves as part of a race but still maintain the authority to name and racialize “others.”

–Calgary Anti-Racism Education (http://www.aclrc.com/racialization)

As Delgado and Stefancic point out in Critical Race Theory – An Introduction (2017), race and races are a product of social thoughts and relations. Race is not objective, inherent, or fixed. There is no biological or genetic reality to race (so-called ‘eugenics’). Race is a category that society invents, manipulates, or retires when it is convenient.

The process of racialization has occurred throughout the history of Canadian immigration. At the recommendation of a colleague who works in immigration policy, I have been reading Vic Satzewich’s Racism and the Incorporation of Foreign Labour: Farm Labour Migration to Canada Since 1945, (1991) which explores the ways by which the post-war labour shortage was filled.

First, it was done by positively racialized Dutch and German migrants, less positively racialized Polish migrants, and at the exclusion of Jewish migrants. The transition to Caribbean migration, a colonial deal, but very much an economic drive one, but also one that racialized Caribbean migrants as temporary and replaceable. That these workers were economically beneficial without being economically burdensome. [See: especially Chapter 4-6 of Satzewich (1991).

The Anti-Black Racism that has been an underlying theme of Canadian racism in a process that has racialized Black migrants as being unable to adapt to Canada.

In 1911, an Order in Council excluded Black immigration on the basis of climate, an inability to adapt to the Canadian climate. Furthermore, Black immigration was racialized as a problem, one that occured in the U.K, and the United States. Key Canadian decision-makers through gendered and racist comments on limiting the immigration of Carribean women, who were viewed as promiscuous from problematic family structures.

Moving now to Anti-Asian Racism, this is another foundation of Canadian immigration which has had devastating impacts felt to this date – from the imposition of the Head Tax in 1885, to the 1914 Komagata Maru/implementation of the Continuous Journey Act, to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923.

Putting things in the modern day, we have seen the historic racialization play a role in key and foundational cases the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in Baker v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 1999 CanLII 699 (SCC), [1999] 2 SCR 817 http://canlii.ca/t/1fqlk where the Officer applied racialized and gendered notions of belonging to Ms. Mavis Baker.

We saw it the Federal Court of Appeal’s decision in Begum v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2018 FCA 181 (CanLII), [2019] 2 FCR 488, <http://canlii.ca/t/hvhff where a s.15 Charter challenge yb a racialized Bangladeshi woman relying on research largely done by racialized experts (needed as a result of the absence of publically available race-based data) was thrown out as not having demonstrated her discrimination.

More recently, explicitly, and all-too commonly, we saw it the treatment of Mr. Kaniche in Khaniche v. Canada (Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness), 2020 FC 559 (CanLII), http://canlii.ca/t/j8csn who was told (in less polite terms) to get out of Canada and back to his home country of Algeria.

We see racialization in the processing of a caregiver program that is majority Filipina women and the refusal at high numbers of African Temporary Resident Visas and Study Permits.

We see links to the past between the Sun Sea MV ten years ago to the much-maligned boat-arriving migrants of the past. We see the way Chinese women were excluded then, and excluded now by the way genuineness and purpose are scrutinized now.

We see the way colour-blindness is now a foundation of decision-making, further diluting those who seek to suggest that racism has become normalized through the process.

We see Courts and Tribunals afraid to mention race, apply the intersectional lenses that we know they are beginning to be trained on, and afraid of moving law beyond the boxed tests of ‘reasonable persons.’

These have all been the the product of processes of racialization, of a racialized system, and the segregating of ‘who is desirable and who is not’ by race. Professor Satzewich writes at page 124 of his book:

“The history of immigration control suggests quite clearly that the Canadian state imposed a racial hierarchy of desirability over the entry of different groups of people to the country and that, inter alia, the imagined community which constituted the Canadian nation was defined in terms of the ‘white race.’ ”

This is a view shared by Professor Constance Backhouse, who writes:

“Immigration laws shaped the very contours of Canadian society in ways that aggrandized the centrality of white power.”

As an optimist, I still feel we have the ability to change this. Not by being continuously colourblind or assuming we are in a post-racial reality, but by delivering equity and racial justice by removing barriers.

The most pressing barrier, the product of racialization, is in the way that post-COVID-19 borders will implement policy (through the breadth of written laws and the application of unwritten policy) to exclude Black and Brown bodies from immigrating to Canada. I highly suspect too, that these individuals will be the first to be removed from Canada when deportations invariably begin – another racialized assumption that they are the least likely (and most resistant) to want to go.

We have already begun to see foreshadowings of this particularly in the context of increasing temporary resident refusals (for those from visa-holding countries). Recent statistics show a huge increase in study permit refusals since the onset of COVID-19 (from a 60% approval rate to 50%), with nearly all of the 80%+ refusal rates coming from African, Central Asian, and Middle Eastern countries that lack Canadian Visa Offices.

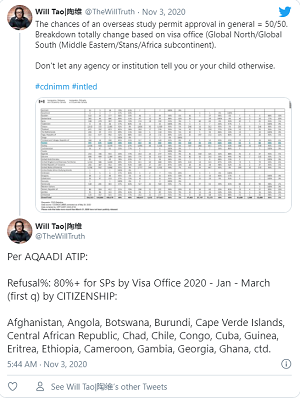

Per AQAADI ATIP:

Refusal%: 80%+ for SPs by Visa Office 2020 – Jan – March (first q) by CITIZENSHIP:

Afghanistan, Angola, Botswana, Burundi, Cape Verde Islands, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, Congo, Cuba, Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, ctd.

— Will Tao|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) November 2, 2020

On the spousal reunification front, the Government has acted to now support extended family reunification, but applications to sponsor overseas are stuck in overseas visa offices barely processing paper-based applications and simultaneously refusing temporary resident visas.

It’s what you see. These are mostly Black/Brown bodies + those who have chosen to enter relationships w/ Black/Brown bodies who are forced to wait/protest. Canada must reconcile (+ justify add’l vetting explanations) for why processing times substantially differ b/n VOs.#cdnimm https://t.co/3BdDemu9YH

— Will Tao|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) November 15, 2020

Without access to a facilitative Electronic Travel Authorization (eTA) process, they can be separated for several years from loved ones and children and are often interviewed over mal-directed cultural concerns.

I don’t want to, but I have to explain to my client from Africa why their sponsorship application will be stuck in Ghana for possibly years whereas a Global North citizen will be reunited within months. Immigration remains system of organized + justified discrimination.#cdnimm

— Will Tao|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) November 15, 2020

This leads to what I think we need to do. I see and hear the advocacy needed to ensure that temporary residents inside Canada have access to permanent resident options, and are granted options post-COVID-19 – the so-call ‘Status for All’ camp.

However, we also need to think about the bigger Global pattern, the social construction of our Canadian borders, and what this might mean for the separated migrant family in particular or the extended family seeking to follow the success of Canadian permanent residents and citizens (siblings and relatives) already established. We need to think about what ‘all’ means where there is a limited pie set to be divided.

We need to start scrutinizing the two-tiered system between Temporary Resident Visas, Electronic Travel Authorizations requiring countries, the different processing times/approval rates + ask ourselves why + reorganize this system in the name of equity and racial justice. #cdnimm

— Will Tao|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) November 23, 2020

How are we going to ensure that we do not create barriers in the way we address immigrants that reproduce the racism and racialization of years past – often done implicitly and in the name of economic benefit?

How also, do we engage in a meaningful discussion about the need to dismantle White Supremacy within immigration? How do we do so knowing that to rebuild the foundation for better, pieces must be replaced and power must be redistributed – bottom up from the margins, away from those who currently hold it and bringing in voices we have historically excluded.

How do we do so, ourselves and our perspectives themselves, being so attuned to the normalcy, perceived objectivity, and correctness that our White/White-adapted lenses have given us to accept that our system is the best, our processes are working, and our tasks are simply to work together to maintain and uphold.

Questions – for sure – ultimately much bigger for one blog piece to tackle.