It has been awhile since I have written on post-graduate work permits and restoration but I feel inclined to do so as a result of a recent decision of the Federal Court in Ntamag v. Canada (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship) 2020 FC 40.

Ntamag and Chief Justice Gagné’s Decision

The facts are not too relevant in what I am about to assess. In short, Ms. Ntamag did not apply for a post-graduate work permit before her study permit expired on 30 November 2018. She only received confirmation of her completion of studies on 4 December 2018. She waited until 16 February 2019 to request that her status be changed to visitor. That visitor restoration was denied on the basis, among three other factors, that she did not accompany a post-graduate work permit application with the restoration application.

For a little background context (although Associate Chief Justice Gagné’s decision does not highlight this), IRCC put out a program delivery update on 14 February 2019 which extended the eligible period in which an Applicant can apply for a post-graduate work permit from 90 days to 180 days. This change also removed the requirement to actually hold a study permit while making a post-graduate work permit application. Furthermore, the provision was applied so that applications moving forward could benefit from the extended period of time.

What the Applicant was presumably trying to do was to restore their status to visitor in anticipation of later being able to make a post-graduate work permit application while a visitor. We have no information in this case about when the decision was made and whether the Applicant could have presumably restored her status to visitor before first before making another post-graduate work permit application. We do know that it appears the application was deficient of information to assess her restoration to visitor.

Perhaps what is more problematic is that as a consequence of the Applicant arguing for the restoration provisions in R. 182 IRPR having one broad (‘shall’) interpretation [see para 15 of decision] – Associate Chief Justice Gagné returns back to what has become a problematic tenant created by another Federal Court case Nookala v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2016 FC 1019 (CanLII), which she applies:

[18] Ms. Ntamag also did not include any proof that she had applied to the PWGPP, nor does her Application mention any intention to do so. Yet, Ms. Ntamag was represented by counsel who was likely familiar with the IMM 5708 process for visa extensions and restoration of status. However, Ms. Ntamag has offered no explanation as to why she failed to include these two pieces of required information. She has also not submitted any evidence that she has applied for a PGWPP since February 2019.

[19] Given that the application is missing several required elements, and that Ms. Ntamag has not explained these gaps in her materials, I find the Officer’s conclusions reasonable.

[20] Second, I am also of the view that the officer did not err in his interpretation of section 182 of the Regulations. Subsection 220.1(1), which is referenced in Subsection 182(2), makes it clear that an Officer must not restore the status of temporary resident’s Study Permit if they are not currently enrolled at a designated learning institution or actively pursuing their course or program. As Ms. Ntamag was not in compliance with these conditions at the time of her Application, the Officer’s interpretation of Section 182 and its relevant provisions was reasonable.

[21] One of the conditions imposed on a PGWPP applicant is that the application be sent before the expiry of the applicant’s Study Permit. As Ms. Ntamag did not meet that condition, she asked to be granted a Visitor permit to be valid until January 1st, 2021.

[22] However, just as section 182 and the 90-day grace period that it provides do not apply to a former student seeking a PGWPP, they do not apply to a former student seeking to obtain a Visitor Permit. Ms. Ntamag could not simply rely on section 182 to obtain a different Temporary Residence status than the one she had held before she applied (Nookala v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2016 FC 1019).

Analysis

It is unclear if the 14 February 2019 PDU was every put in front of the Court in this case as an argument. Had the Officer ignored this development and the intention created by IRCC to remove the requirement to hold a study permit (and allow the holding of a visitor record) at the time of application, perhaps the reasonableness of the decision would have been put in question.

This decision also re-highlights a fundamental disconnection between the wording of R.182 IRPR and the application in practice that it has taken through policy instruments and other processes.

R. 182 IRPR states as follows:

Restoration of Temporary Resident Status

Restoration

182 (1) On application made by a visitor, worker or student within 90 days after losing temporary resident status as a result of failing to comply with a condition imposed under paragraph 185(a), any of subparagraphs 185(b)(i) to (iii) or paragraph 185(c), an officer shall restore that status if, following an examination, it is established that the visitor, worker or student meets the initial requirements for their stay, has not failed to comply with any other conditions imposed and is not the subject of a declaration made under subsection 22.1(1) of the Act.

What does that ‘restore that status’ ultimately mean?

IRCC has provided up instructions, that as counsel for Nookala highlighted in their post-case submissions [see para 24 of that decision] asks officers to look at restoration not through a backward lens of restoring an individual to the status they held but rather to a status they are able to meet, if they still meet the initial requirements of their stay.

Eligibility requirements for restoration of status

Applicant requirements

The applicant must

-

apply within 90 days of having lost their status;

-

meet the initial requirements for their stay;

-

have not failed to comply with any other condition (e.g., working without being authorized to do so);

-

meet the requirements of the class under which they are currently applying to be restored as a temporary resident.

-

have lost their status because they have failed to comply with any of the following conditions:

-

Paragraph R185(a)The period authorized for their stay.

-

Subparagraphs R185(b)(i) to (iii)The work that they are permitted to engage in, or are prohibited from engaging in, in Canada, including the

- type of work,

- employer, and

- location of work.

-

Paragraph R185(c)The studies that they are permitted to engage in, or are prohibited from engaging in, in Canada, including the

-

type of studies or course,

-

educational institution,

-

location of the studies, and

-

times and periods of the studies.

-

-

When IRCC’s own policies are asking Officers not to be too literal, the Court is still returning to the legal provision and taking a literal interpretation.

As Nookala’s counsel provided, IRCC’s instructions (still up four years later) suggest:

The phrase “initial requirements for their stay” should not be read too literally when it is being applied in the context of a restoration application, and the requirements of section R179 should not be applied rigidly in that regard. The preferred interpretation in this context would be that the person seeking restoration must meet the requirements of the class under which they are currently applying to be restored as a temporary resident. The desired approach to the restoration provision of section R182 is to be facilitative and consistent with the current approach to extension applications of the provision in section R181, since the two provisions are similar in nature and section R181 actually refers specifically to the requirements of section R179.

Incompatibility with Current Practices

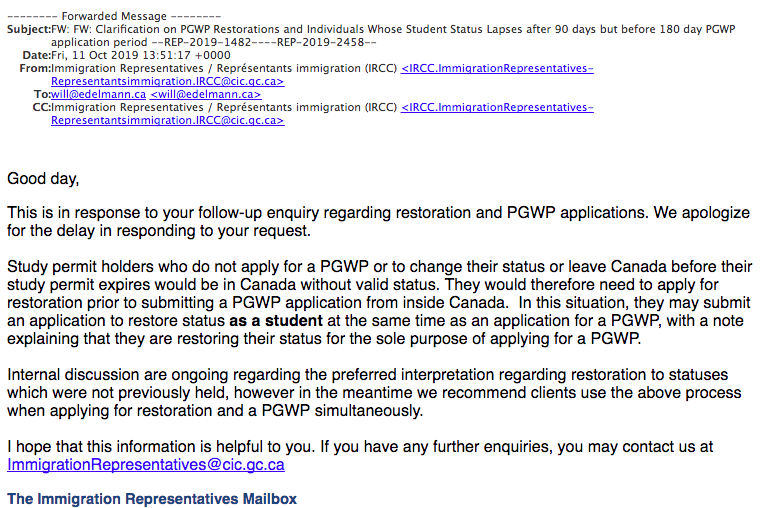

IRCC’s current recommendation on restoring post-graduate work permits is actually the very process Justice Mactavish found problematic in Nookala. As per, this Immreps response below, a transitory restoration to student is now the preferred process:

Last year, while this process was unclear I was successful in restoring someone via a transitory visitor status doing the same thing that the Court in Ntamag found problematic except for the fact I attached a post-graduate work permit application. That cannot be, however, the principled difference – especially if the Applicant has 180 days rather than 90 days from completion of studies and could arguably complete both a restoration to visitor and make a new post-graduate work permit application within the applicable period [subject to R.199 IRPR].

This cases also raises questions about IRCC’s many other programs that operate on a model where restoration to a status not held is a basic tenant. For example, spouses who have lost status but are applying for Inland Sponsorship are able to restore their status to work permit holder. We frequently assist out of status workers who no longer have an employer/arrangement in Canada to restore their status as a visitor while awaiting a new employment opportunity.

It is important to note that while the case law so far has been negative (particularly of late) on the PGWP matter, I would suggest that many cases have not yet seen (and may never see) the light of day. I still believe in some of these cases pursuing either settlement with Department of Justice or reconsideration options might seek remedies better than having the Court need to reconcile two presently irreconcilable provisions.

That being said, if Justice Gagné and the Nookala impossibility of restoring to a transitory status is continued, all of IRCC’s guidance on restoration through a transitory study permit status and the regulatory changes that allow an individual not holding a valid study permit to apply for a PGWP, are rendered irrelevant in the context of restoration.

Conclusion

I believe that for the interest of fairness and to reflect practice, restoration should be given a broader interpretation than that meaning one can only restore to a status held. It should be forward looking.

I think IRCC should urgently clarify instructions for Post-Graduate Work Permit restorations (something they should have done years ago) and then hopefully lawmakers can amend the R.182 language to clarify that the restoration of these statuses is a forward (not backward) looking endeavour.