Oh, the joys of our immigration practice and the frequent changes it brings along.

I am scheduled to speak on study permits this upcoming Friday for the Canadian Bar Association’s National Conference. I finished my materials a week and a half ago – presumptively thinking that I covered almost everything I could regarding study permits (combining both pre-COVID materials I had prepared and post-COVID guidance).

Friday rolled around and there is a whole new program delivery guide was posted. I found out Saturday morning as I was midway through watching the MJ/Bull’s documentary The Last Dance (I’m a bit behind on these type of things). H/T to Toronto-based immigration lawyer/specialist Robin Seligman for the Linkedin update that caught my eye.

I pulled a marathon Saturday, wrote about the Federal Court/prepared my judicial review Sunday, and now I finally have some time to breakdown the delivery instructions with you. I will also touch briefly on the CBSA’s guidance on international student entry subject to the Orders in Council that superstar litigator (someone who I personally foresee as a future Federal Court judge), Aris Daghighian received as part of his litigation against IRCC on the application of the Order in Councils (OICs) which refused the entry of a father to attend his child’s birth.

For reference materials, follow along here (for the Program Delivery Instructions). We will discuss the CBSA guidance/directives through screenshots shortly.

IRCC Not Refusing Applications for Non-Compliance

As stated on the instructions:

Until further notice, IRCC offices will not refuse an application for non-compliance. IRCC officers will continue to request additional supporting documents or necessary actions (such as biometrics and medical exams) as part of the application process and will keep the applications open until documents are received or evidence is provided that action has been taken.

This, along with the 90 day response periods are generous, but at the same time can create challenges with other third parties (employers, schools, etc.). While processing officers are also bringing forward the applications and paperng applications, you should do the same on your end as an applicant/study permit holder.

I would also make sure to save a copy of the instructions so you can share with those who may not be familiar with the changes and may challenge your ability to work.

Submitting Applications Without Certain Documentation

As I wrote in my post for Edelmann’s blog last week, updating files and timing further submissions is going to become an important skill.

As a temporary facilitation measure, students applying to extend their status will be allowed to submit an application without a letter of acceptance or proof of enrolment. In lieu of the letter of acceptance, the applicant should submit a letter of explanation indicating that they are unable to submit the requested document due to their school’s closure.

Once these documents become available, applicants should submit the documents using the IRCC Web form. If no documents are submitted by the time CPC-E is ready to process the application, the documents will be requested by the processing officer as per the instructions above.

It should be noted that this is a temporary policy. It is foreseeable that at a certain point in time these instructions will be rescinded. While it is hoped that applicants will have sufficient time to respond, it is not unheard of to have to have anywhere from one week, to two weeks, to a month to obtain documentation. This still may be an issue down the road so I see very little benefit in not trying to stay on top of things.

Post-Graduate Work Permits

IRCC has provided a helpful exception – allowing individuals to apply for a PGWP while they are awaiting a letter of completion or final transcript. This is crucial as it allows students to start working, assuming they still hold a valid study permit at the time of their PGWP application.

The relevant instructions state:

As a temporary facilitation measure, applicants who apply for a post-graduation work permit will be allowed to submit an application without their letter of completion or final transcript. Applicants should submit a letter of explanation indicating that they are unable to submit the requested documents due to school closure. Once these documents become available, applicants should submit the documents using the IRCC Web form. If no documents are submitted by the time CPC-E is ready to process the application, the documents will be requested by the processing officer as per the above procedures.

Restoration to Student/PGWP

I still think IRCC needs to provide more detailed ‘step-by-step’ instructions on how to apply for restoration to PGWP, via a restoration first to student.

The relevant instructions state:

IRCC has clarified that applicants who need to restore their status will also be eligible to apply without their letter of completion or final transcript.

Documentation – Designated Learning Institutions (“DLIs”) Need to Take a Bigger Role.

As the instructions state, there are going to be several points where international students are being requested to provide updated documents which largely originate from the institution.

Applicants may have to submit additional documents from the DLI confirming which part of the program was completed in Canada.

There is also an important note that states as follows:

Note: For applicants currently outside Canada who are scheduled to begin studying in May or June 2020 but who do not have either a study permit or approval on their study permit application, time spent pursuing their studies online will not count toward their eligibility for a post-graduation work permit.

Right now international students (both abroad and at home) are in a weird limbo around part-time studies and whether or not they need a permit to engage in online studies. While IRCC has given an exemption for students who are unable to study full-time as a result of institutional issues in maintaining their status, they likely be reminded of this only years from now when they are preparing their PGWP applications and recognize this huge gap. DLIs need to take added steps to document and be able to assist students in the preparation of letter of completions that may contain more detail than usual. Many times, and especially with turnover, these important notes to file are lost and students find themselves having to put the blame on the institution if their applications are refused, leading to both liability and litigation risk.

More on International Student Advisors (RISIAs) shortly.

One Policy Recommendation

IRCC states the eligibility to work after submitting PGWPs as follows. Note that the wording of ‘before the expiry of their study permit’ presumptly suggests that implied status applicants who were awaiting a study permit prior to making their post-graduate work permits. must wait until their PGWP is approved before they start working.

Work authorization after submitting a post-graduation work permit application

As per paragraph R186(w), graduates who apply for a work permit, such as a post-graduation work permit, before the expiry of their study permit are eligible to work full time without a work permit while waiting for a decision on their application if all of the following apply:

- They are or were the holders of a valid study permit at the time of the post-graduation work permit application.

- They have completed an eligible program of study.

- They meet the requirements for working off campus without a work permit under paragraph R186(v) (that is, they were a full-time student enrolled at a DLI in a post-secondary academic, vocational or professional training program of at least 8 months in duration that led to a degree, diploma or certificate).

- They did not exceed the allowable hours of work under paragraph R186(v).

Unfortunately, much of this processing time is out of the students control. Also, with many students having had to navigate COVID and changes to their final semesters, many have had to put in a last extension prior to graduating. The reality is it could be several (read: five, six plus months) before they are able to obtain their PGWP.

I suspect this is just a small gap but one that should be filled immediately.

The March 18th Rule

One of the reasons international students and their issues at the border may have been heard about less than other groups during COVID-19 is as a result of the firm date of March 18th, chosen by IRCC at which time either students must need to hold an existing study permit or have their letter of introduction dated before.

In a way, the strictness of this date, has masked the many challenges applicants in Canada are having with their study permits and as well the challenges institutions are having in predicting their numbers for Fall/Winter programs.

Disclosure from the CBSA Directives

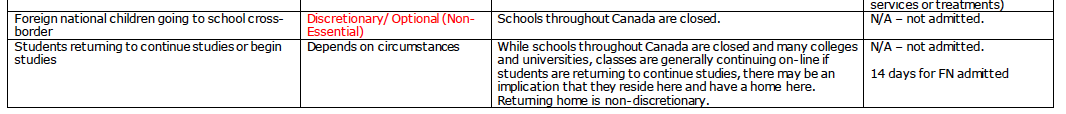

We learned from the directives the following on international students who are seeking to enter Canada.

We know the situation is very dynamic with different provinces and schools taking different positions as it relates to online or in-person classes (with social distancing).

Notwithstanding the March 18th rule, student who hold valid study permits may still face challenges returning and are advised to bring proper paperwork to the Port of Entry.

Institutional and Applicant Mistakes On the Rise

As I discussed above, I think this a period of time where institutional and applicant mistakes may be magnified, with delayed consequences that may be felt even possibly several years down the road.

Unfortunately, in my own practice I have had to step in on many a recent case where the mistake emanated from a international student as the College/University. This may be as simple as endorsing the completion of forms without an adequate knowledge of the applicant’s entire immigration history, to advising a student to indicate an excessive set of available funds without those funds actually being available.

With international students bringing so much revenue to schools and program, the very least a DLI can do (from my perspective) is pay for the training of staff to the take the RISIA course or possibly even the RCIC course. Advisors themselves should build in as many caveats into their advice as possible. Twenty/thirty minute consultation sessions are helpful but I cannot count how many times I learned disclosure from clients weeks and months later. Many students have had little-to-no role in past applications that were coordinate by parents, family members, or agents.

I also recommend that schools consider engaging immigration lawyers as part of their staff team. The average immigration lawyer makes $75,000 (as I learned from Marina Sedai) from a recent talk for the CBA National Online Immigration Conference. That $75,000 is not coming easy either for many of my colleagues. It may be a good opportunity to get legal expertise and advice (particularly on the research/documentation/risk management side).

For student applicants, this is also a time to be extra diligent about document collection, storying, version management, form completion, among other areas.

I think it is also a time for student advocacy and for institutions to do a better job at listening to students and incorporating students into their programming and advisory services. I recently did an interview for a newspaper based in Montreal expanding on my some of my policy recommendations in general but I thought I’d tackle the new changes in this piece.

As discussed, I will be chatting more about Study Permits, pre/post-COVID this on Friday at the Online National Conference.

See you then :).