‘Young, Single, Mobile, and Without Dependents’ – Why the Courts Need to Step In

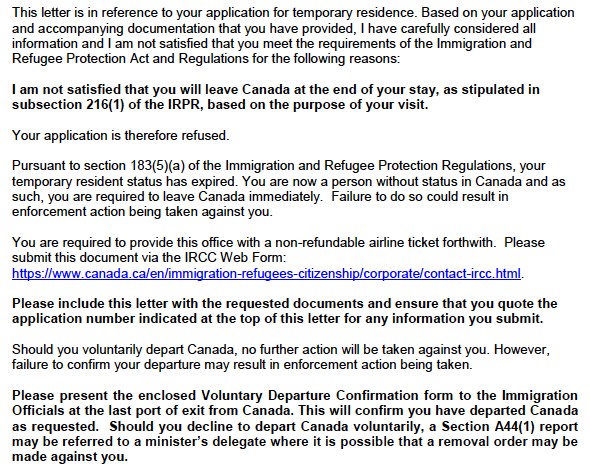

Among a few frustrating trends, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (“IRCC”) continues to refuse temporary resident applications (namely visitor visas and study permits) by single