On 15 August 2016, Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, the Hon. Ralph Goodale made an announcement that the Government of Canada will be investing up to CDN $138 million dollars to transform the immigration detention infrastructure in Canada.

This announcement comes on the heels of a string of deaths that occurred within immigration detention, that many in the legal and immigrant/rights advocacy community believe may have been entirely preventable.

Minister Goodale’s speech his reforms have several objectives. As reported by the CBC, the reform objectives are as follows.

The reform objectives

- Increase the availability of alternatives to detention.

- Reduce the use of provincial jails for immigration detention.

- Avoid detaining minors in the facilities as much as possible.

- Improve physical and mental health care offered to those detained.

- Maintain ready access to facilities for agencies such as the Red Cross, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees as well as legal and spiritual advisers.

- Increase transparency.

With respect to the Vancouver/Pacific Region, Minister Goodale specifically noted the need for a new detention facility.

As per a simultaneous backgrounder titled Federal Immigration Detention Infrastructure, the Government of Canada notes that the only Immigration Holding Centre is a short-term facility in the Vancouver International Airport that can hold 24 detainees for a maximum of 48 hours. The release notes that there is “no on-site access to the IRB, no access to educational programming, nor health care providers on site.”

As a bit of an insight to the detention process from a practitioner’s perspective and as well to shed light into some of the on-going issues I have seen I wanted to do a post highlighting the detention process and my experiences, broadly speaking.

In so-doing, I do want to note that my personal experiences with individual Canada Border Services Agency (“CBSA”) officers has generally been very good. They have some of the most consummate professionals working there doing what I can see from their eyes too is often an unenviable and heartbreaking task of removing individuals from Canada and in some cases, separating families.

In writing this post, and sensitively so, I will not mention any names of any individuals or even refer to my own cases and speak to everything in a very broad manner. Given that I still actively provide services to many clients (and hope to continue to do so) I hope my readers forgive me for the lack of intimate detail in this post and my emphasis on protecting privacy and the legal process. I also want to share various recommendations I have relating to the process of detention.

Investigation and Detention

Before the individual gets detained, generally speaking there is the requirement for a preceding investigation. The investigation is usually undertaken by CBSA (often times on the recommendation of another agency, such as the police or Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada (“IRCC”)) and in a majority of the circumstances CBSA will attend to the investigated subjects door with little to no warning.

I will specifically gloss over, for the purposes of this overview piece, the quite important discussion of the Right to Counsel and when it arises in the context of an immigration detention. This issue is legally sensitive and as such will require it’s own post and a later time. What is important is that the Right to Counsel must be provided to the individual upon their detention.

During the detention, and as alluded to Minister Goodale’s speech, in addition to assessing the potential grounds for issuing an inadmissibility report, the CBSA officer will be determining whether the investigated individual should or should not be detained for immigration purposes. This inquiry depends, broadly, on three factors as set out the Immigration and Refugee Protections Regulations R.244. To summarize:

- Is the person unlikely to appear for further immigration proceedings (i.e. are they a “flight risk”)?

- Is the individual a danger to the public? and

- Is the individual a foreign national whose identity has not been established?

Each of these three factors – flight risk, danger to public, and identity also have their own sub-factor assessment. I would suggest, as good reading sections 5.6 to 5.8 of CBSA enforcement manual ENF – 20 Detention, as these factors are very important but too lengthy to discuss within this summary-based blog post.

I did, however, want to touch upon two important factors that I generally find play a huge role and perhaps on points where changes can be made to the way the need to detain is assessed.

(1) Language Issues

I find that language issues, particularly where an individual attempts to answer questions in a language that is not their own, or has challenges with interpretation can be a major challenge. Being approached by two officers, often in broad day light and in a public place, can be very stressful but too often mistakes are made inadvertently.

These mistakes later can be used as evidence of non-compliance later on. It is important for an individual who is being questioned to be truthful at all times. I have seen several cases where individuals give false statements with hopes that agreeing or accepting the officer’s questioning may lead to further consequences.

Finally, the unenviable task of interpretation can often go wrong. Interpreters may have misheard or may be misinterpreting the statements of the detainee (for better or for worse). I have also seen on several occasions individual interpreters accidentally go beyond the job of translating to actually advising and assessing the individual’s statements. As the Officer generally does not speak the language, this becomes a major issue where this information is the sole basis for an Officer’s affidavit in support of justifying detention.

I would suggest expansion of Officer’s able to speak the language and assess the quality of the translation and in-person translation, where possible, would be desirable.

(2) Strong Ties to Canada

I find that this factor is a very tough one and tough to address. Rarely, having reviewed many Officer transcripts, have I seen Officer’s directly ask whether “if you were found inadmissible to Canada would you leave Canada if required?” The line of questioning usually goes around – “where is home?”, “do you have family in your home country?”, and “who do you live with in Canada?”

Strong ties to Canada, from a logical standpoint, would give way to the sense that an individual would appear for future proceedings but it is interpreted in immigration law often as a reason an individual may choose to hide and be a flight risk. Even if I were asked this question, with my knowledge, I would feel trapped between a rock and hard place trying to provide this answer.

I would suggest that there should be more policy guidance on how an individual is supposed to answer this question. For example, at a detention review, one of the strong factors that allows an individual to get released is the presence of a strong tie (immigration bondsperson, ideally who is a Canadian Citizen).

I can attest to the fact that most of the time, by the time I get the call from the potential client (usually through their family member) all of the above events have usually occured. Below I discuss briefly what happens when an individual “goes under” and is taken into CBSA custody.

What Happens When an Immigrant is Detained in the GVRD Area

Once detained, the individual is statutorily granted a 48-hour detention review where their detention is reviewed. Depending on when the individual is arrested, usually must occur within 48 hours. For example, if an individual is arrested on a Thursday, and it is a long weekend, they will not get their detention review until Monday.

In Vancouver, an individual is often transported to the Immigration Holding Centre at Vancouver Airport (“YVR”) before they are brought in either to the CBSA Holding Cells at 300 West Georgia Street or a Provincial Detention facility.

As addressed by Minister Goodale, one of the challenges is that the families of those detained often do not know what facility their detained family member is at and it is not uncommon for there to be a substantial gap between the individual detained and the individual being able to make their first call letting their family know where they are. This is a major challenge.

Furthermore, there is currently a mixing of general population and the immigrant detainee at many of the provincial correction facilities. Access to counsel is quite limited (many of these facilities are 1.5 hours+ outside of Vancouver), booking space to see the individual is quite difficult, and even family members have difficulties getting messages to their detained loved one through the prisons phone system, particularly where they do not even know the correctional facility. I have often tried to access clients in detention and are told that the earliest time I can book is two days after their hearing date. There is a lack of coordination currently between CBSA and Provincial prison authorities in providing this critical space.

In Vancouver, there is a great liaison at CBSA who does assist in connecting, where possible counsel to this information. However, often times, without a Use of Representative Form signed, this individual is hand-tied in providing that crucial information to non-retained counsel.

Overall, I think there needs to be some serious re-thinking of putting individuals who have committed immigration offenses that would be considered non-criminal (working without authorization, not actively pursuing studies, even overstays). Out of all the comments I hear from those I have assisted in being detained, the most repeated comment (other than the comments about the food) is that they were very shook-up by having to share a cell with a common criminal and felt very intimidated and frightened.

Having represented several clients through the immigration detention process and assisted several families in the process of tracking their loved ones down after the process.

Interview and Questioning

After detention, it is not uncommon for other Officers to meet or call the individual. This is where Inland Enforcement at CBSA gather their evidence. They often will simultaneously call other individuals/witnesses who may have knowledge of the inadmissibility claims.

A more formal interview with a second Officer is not uncommon for the facts to be better flushed out in support of the inadmissibility report/finding.

Minister’s Delegate Review/Referral to Immigration Division

The next step, which usually occurs on the first full day of the individual’s detention, is the Minister’s Delegate Review. Depending on the immigration offense (topic of another post), the Minister’s Delegate either has the authority to issue the removal order or will have to refer the case to the immigration division for an admissibility hearing.

The challenge with this Minister’s Delegate Review, often the last time for the individual to try and change the mind of CBSA or add new facts to file, counsel is generally not given any disclosure and, other than the word of family members of the detained and the detained themselves, will have no knowledge of what occurred.

In terms of recommendations, I think that having disclosure delivered the morning of the individual’s detention review and inadmissibility review is much too late. Officer’s original affidavits and notes of the investigation should be made available prior to the Minister’s Delegates Review so that any factual clarifications can be made prior to the issuance of the removal order or referral to the Immigration Division. Counsel who receive a disclosure package mere hours before the Immigration Division inadmissibility hearing usually have a very difficult time defending their clients or even gathering the basic facts required for a due diligent inquiry.

As another aside, I think that more immigration offenses (for example, the “not-actively pursuing studies” violation) should be referred to the Immigration Division. I understand that this would put a greater strain on the Division, but I think that in the context of the fact-based nature of that inadmissibility (similar to unauthorized work) that this would be appropriate.

Detention Review and Inadmissibility Hearing

After 48 hours (not including again weekends or holidays) the individual is provided a detention review and inadmissibility hearing. In Vancouver, in most cases where an individual does not have private counsel, the reports are dropped off with duty counsel in the morning. Duty counsel in Vancouver, individuals who generally get paid legal aid to assist, are often given a stack of documents and must make the early morning rounds to advise each clients on what has occurred and what is going to occur in their inadmissibility hearing. The challenge is, there is simply not enough time (without private counsel involved) for a duty counsel to provide full legal advice. The disclosure packages could be several pages and include several affidavits, that in an ideal world would be dissected fully to ensure the investigation and detention was done lawfully and accurately.

With the greatest respect to the amazing, selfless lawyers that do duty counsel work (of which I hope to soon be one), I have heard from many detainees after the fact that they had absolutely no clue what the process was in the morning before their detention review and that they were advised by the duty counsel to “admit to everything” at Immigration Division in a ten minute conversation. A few of the better duty counsel in Vancouver, who I have seen conduct inadmissibility hearings and detention reviews, have taken the approach that where there is an arguable case or where there are issues with the investigation that an adjournment should be pursued. I also agree with that approach. It is important to note that inadmissibility hearings and separate from detention review.

While CBSA may be hesitant to consent to release where a removal order has not been issued, detention and inadmissibility are two distinct issues and to try and admit fault to secure release in my end is often not in the client’s best interest. Arguing for interim release and suggesting a later date for the admissibility hearing, gives you the ability as counsel to prepare the case and review the evidence fully before making any admissions to CBSA’s allegations against your client.

As private counsel on several files, one of the benefits I have been able to deliver is a plan to ensure CBSA is comfortable with detainees release. This involves setting up a reliable bondsperson, an acceptable amount for the bond, and clarifying where the individual will stay, and negotiating some of the important terms and conditions. Often times, this will also have to involve family making arrangements to ensure that the individual will comply with requirements to check-in and not engage in any activities that could lead to further immigration compliance issues. Having CBSA comfortable, can avoid a contested hearing at the Immigration Division where the detainees fate is at the hands of an Immigration Division member.

Should the detainee be successful at a detention review, showing that the conditions that led to their initial detention cease to exist, the individual will be released. The paper work takes about an hour to an hour and a half. Depending on when the release order is issued by the Immigration Division member, the individual may be released either from the CBSA holding cells or they may have to return to the Provincial Custody facility. One tiny piece of advice, I have for accompanying family members is to make sure that the bondsperson is available that day, has payment in the approved form, and that an extra set of clothes are brought for the detainee as often their clothes are left in the detention facility and not brought with them to CBSA Holding Cells (where they are given standard jumpers to wear instead).

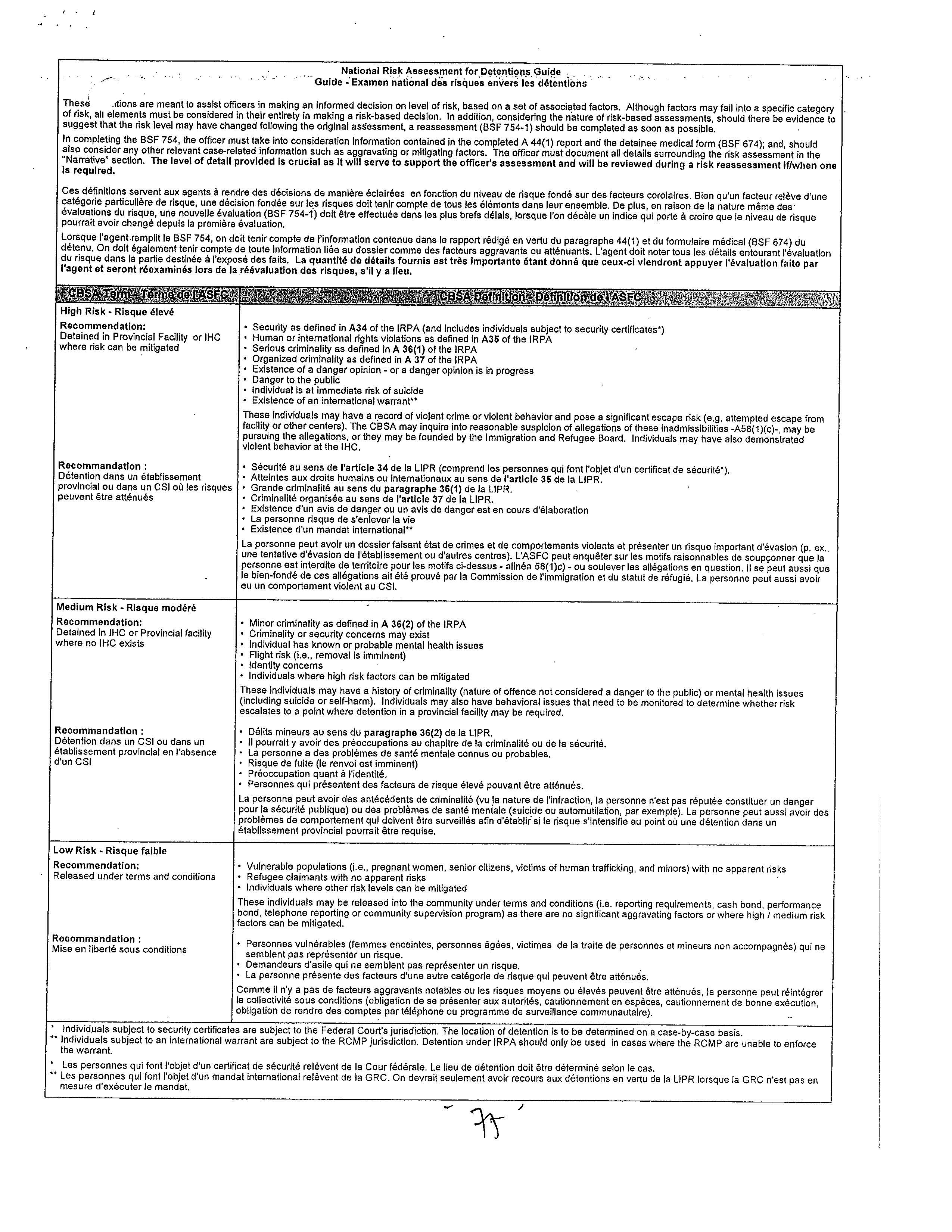

National Risk Assesment for Detention Guide (BSF 754-1)

I figure this document may be interesting to some stakeholders as to the motivating factors that lead to detention. This chart lays out the risk assessment detaining Officers must assess:

You can download the document here: National Detention Review Guide

My Recommendation for the Detention Process

In general, I would provide the following recommendations to Minister Goodale about our detention regime:

- Where possible, and in cases where the individual appears prima facie, low risk either provide the opportunity for voluntarily compliance or explicitly ask whether the individual will be compliant. Faced with the possibility of detention, I am pretty certain for these cases the compliance rate will be very high and this will save on taxpayer resources and detention resources.

- Implement electronic monitoring as an alternative to detention in all non-criminal, first-time cases.

- Provide more readily interpreters (i.e. accompanying interpreters rather than phone interpreters) where possible. Where it is clear the individual’s native tongue is not English, clearly indicate the purpose and consequences of the interview and the possibility of detention as an end result;

- Prior to detention, allow the individual the opportunity to make a call to a family member to advise them on what has occurred and what the process and timeline will be;

- Once detained, detain the individual in a facility separate from general population and allow access to family members and legal counsel without the need for a prior appointment;

- Once detained, have notice of detention delivered to the individual’s appointed next of kin. This individual would not allowed to an individual who may have contributed to the inadmissibility of the individual. This would also allow the individual to seek a surety/bondsperson at an earlier stage.

- Once detained and the detention report and notes and finalized, make available to the detained individual and their legal counsel prior to the Minister’s Delegate Review with the opportunity to formally make submissions requesting early release or submissions about rescheduling the review at which time further evidence could be provided.

- Try and facilitate the arrival of detainees at CBSA in a manner not visible to the general public who may be at CBSA. I have seen on a few occasion young children, who are accompanying their mothers have to watch a chain of detainees in cuffs go by. The effects of this on our young children can be devastating.

- Encourage earlier provision of Disclosure material and encourage CBSA to be flexible in allowing a delayed Immigration Division hearing when requested by detainee/counsel.

- Amend the “unlikely to appear” detention guide to provide clearer guidance on how a detainee can prove this and that they have the onus to prove this during an initial interview. Provide additional time to the individual to secure the missing pieces (i.e. 24 hours) prior to their detention.

I hope this post was enlightening. I am glad the Government is taking steps to address the issues. In perspective, more money (without significant overhauls of the process and procedure) can only go so far…..