First – to Frame

I have been trying to write this piece for over seven years. I had this constant struggle with whether this story should remain a family secret/dinner table fable or whether there was a greater utility in sharing it publicly.

I have decided, ultimately, there is. First, I was inspired by my mentor Dr. Henry Yu who had this piece written about him in the Georgia Straight which he delves into family and delves into his motivations for doing the work that he does. Second, recently, I have read a lot about China and the Chinese Canadian diaspora in Canadian media (about the country and the people, to be specific and certain) that discords from my own experiences and threatens to paint over the history of myself and many others with broad brush strokes represented by a current politics many of us want nothing to do with.

For first and second-generation (and many further past generations – I like to call us all X-Gen’s) our histories are inextricably tied and always will be tied to our ancestral homes. China (and for others Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau) will always be a home for us. Our way of living of bringing in the past into our present (the same missions we’re fighting in Chinatown, Punjabi Market, and Indigenous communities across) is for us, our form of existence and survival as settlers between homes.

For many of my friends with Southern Chinese roots, these stories come from cities such as Xinhui, Kaiping, Panyu, Enping and Heshan. Sadly, I have yet to visit these towns although it is high on my to-do list to study how families made it generations through distance and exclusion. I know that every time I watch documentaries where youth or Vancouverites go back to meet their elders, speaking their Cantonese, Toishanese, Hakka, I get the feels. Even though I don’t speak Cantonese, I share the same warmth. My own ancestral dialect of local Shaoxing is a weird mix of Mandarin and Shanghainese that I find delightful and complicated (as a kid who grew up with an ear for Shanghainese, and a mouth that spoke on basic Mandarin). Our dialect (coming from the South – Nanfang 南方)as opposed to the North (where standard Beijing Putonghua 北京普通话 comes from) – also leads to understanding bits and pieces of Cantonese.

Linguistics is just one example. When we look beyond what divides us, we find some similarities like this that we forget to appreciate and cherish. This extends to those who come recently and who may bring with them different means than many of us originally came with.

Through writing this piece and sharing just a bit of my Chinese Canadian story, I hope that for those people and pundits who cannot separate the physical space, the people, and the Government, that gives a different lens into past, present, and future. That they can give space and room for Chinese Canadians to share their stories and to recognize that with over a billion people there exists more than two sides to the coin of China and how the country and culture has shaped our identity, historically and continuing today.

We are not monolithic, we are different, coming from different political histories, levels of historical and current affluence (of mind as well as money), periods of migration – that all sought Canada as our country of opportunity and new beginnings. That did not change then and does not change now. Our stories are worth sharing because they are unique, different, and for many of us – extremely humbling and full of our rooted values of filial piety, respect, and community. Again, there’s so much that ties us together and makes us each other’s keeper in ways we have not yet begun to appreciate.

Here’s just a slice of my mooncake I hope to share.

Taoyanzhen, Shaoxing – My Paternal Ancestral Hometown

This is where the grandfather and the great-grandfather were born. Taoyanzhen (陶堰镇)Shaoxing (绍兴)Zhejiang Province (浙江省).

When I was young, I thought before that my ‘ancestoral home’ was Shanghai (上海)as that was where mom and pops grew up. I still remember no mention of Shaoxing in that brown shoebox project my dad helped me with in elementary school where he wrote over it in beautiful calligraphy, ‘My Ancestral Home’ (我的家乡). In the few vacations I made in the city as a child, teenager, and later young adult – it never felt ancestral or ‘Chinese.’ It felt like Paris. Other than the food, to be honest I was often left craving more. I was a bigger fan of the historical attractions of Beijing than the fast metros of Shanghai.

I found what I was looking for in Shaoxing, and specifically my ancestral hometown village of Taoyaozhen (about a 15-20 minute taxi ride outside of the City Centre). For those that are wondering, – yes the ‘Tao’ is the same ‘Tao’ as my last name. This is a village of people theoretically related to me (although many have intermarried so last names of various type are in abundance). I almost/kind-of had that Punjabi-wedding meet and greet feeling that many of my close friends speak about.

Here is the look of one of the main ‘streets.’ The river serves as a canal with draw bridges. It’s very, very working class. Toilets are a hole in the ground. The whole town a series of intricate mazes and bridges.

For more info about the town check this out link in Chinese.

Going to Taoyanzhen in 2012

When my pops and I went to Taoyanzhen, Shaoxing in 2012, we took a taxi to town entirely lost. My father had been a bit hesitant about going. To him the ‘past was the past,’ and he feared that we would either find nothing from the past or find something that would create additional familial burdens.

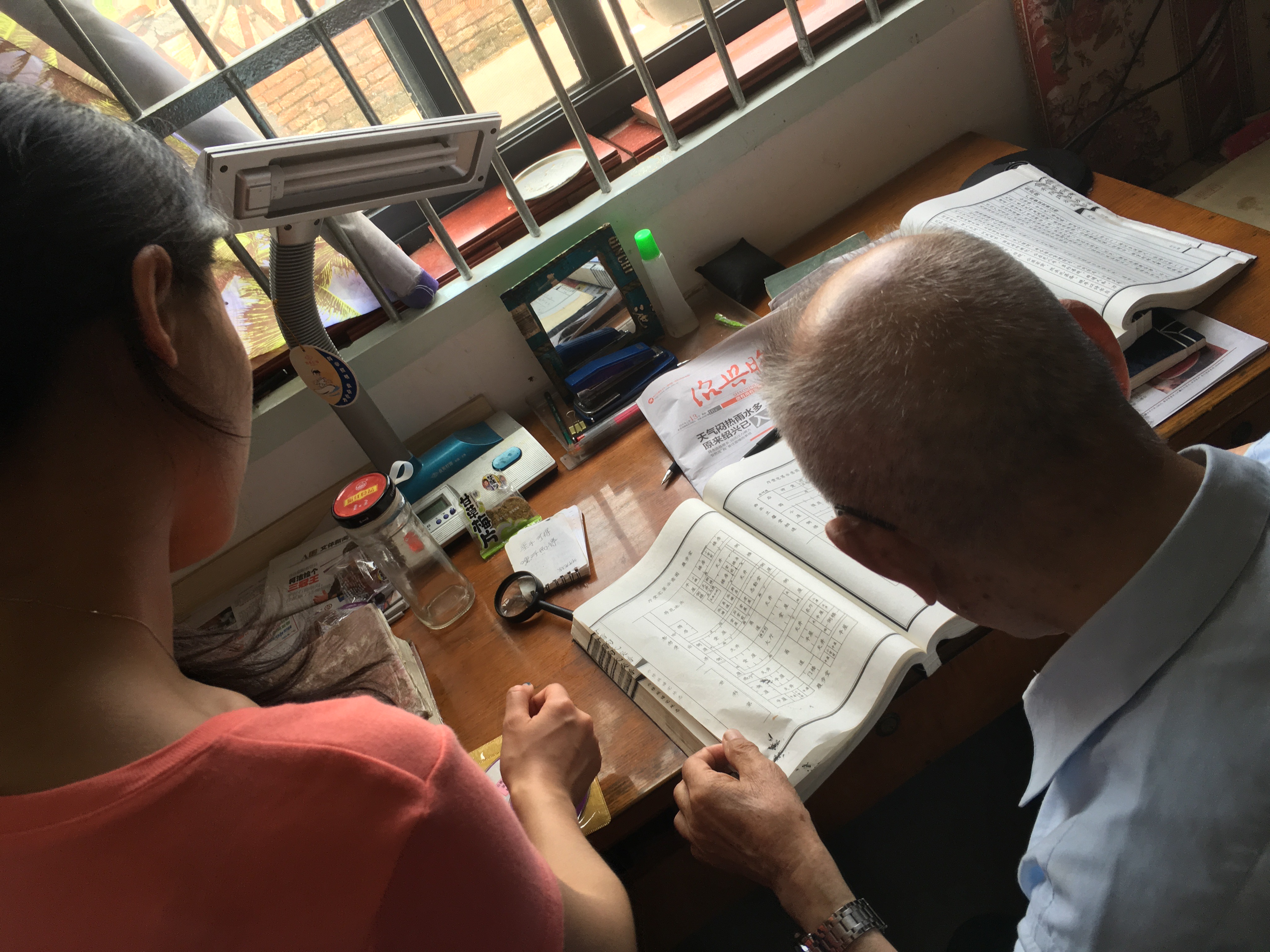

After getting off the train from Shanghai (about two and a half hours away) and hopping into a taxi, a couple individuals in town saw us get off with our Western backpacks and told us we needed to check in with Master Tao (陶老师) who would know how to help us find the information we were seeking. Turns out, Master Tao was the town historian and archivist. In fact, he was doing a family mapping project for the whole village. He sat down with my Dad and proceeded to tell him about his father and his grandfather – from memory. It was a fascinating history for someone who studied the filed in undergrad. It turns out my grandfather left town for Shanghai really early at the age of 12 and never looked (or went) back.

Master Tao showed my father the project he was working on. I remember he also treated us to the famous local Shaoxing corn and I had my first bowl of Shaoxing yellow wine (more on food later).

The project ended up being a book (that my father has and now sits at my mom’s house) and a DVD that he provided me the last time I went there in 2016. I have a copy of the family tree on my laptop which I look at frequently (to the amusement of my spouse Olivia).

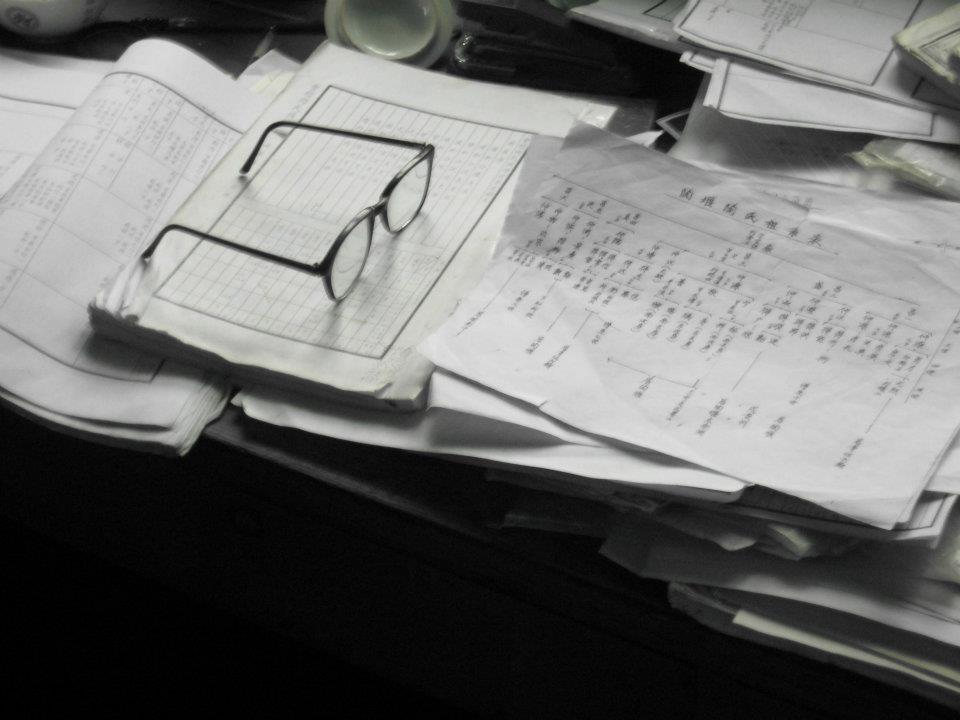

My late father was quite the amateur photographer. I love this photo of the Master’s glasses with his work sheets. The photo is nice, so it must have been my father who took it (I’ll own up to my bad photography). At that time he had not yet finished the full collection (the DVD which he gave Olivia and I in 2016).

The Master took us on a short walk to my Great-Grandfather’s home. I don’t think I ever appreciated how good I had it (even in the basements of my childhood) until I saw these humble beginnings.

While I am sure the room looked different then, thinking about my great-grandfather, my great-grandmother, and my grandfather, together in the space I was now standing gave me shivers. Looking at it now still does.

After touring the (literal) ancestral home, my father was re-introduced to and spent time bonding with my father’s cousin (his grandfather’s younger sister’s daughter [could be wrong on generations here]. I believe she hadn’t seen my dad in some thirty years at that time but had faint memories of going to Shanghai on a few occasions to see him.

After a great meal, the next day my father and I went exploring around Shaoxing. The famous author Lu Xun has his ancestral home near the City core so we went there and shared plate of famous Shaoxing dishes, some referenced in Lu Xun’s work. Shaoxing food is known for it’s liberal use of Shaoxing Yellow wine. It is one of my favourite cooking ingredients – although sadly the ones found in your local Asian grocer bear very little resemblance to the real thing. Shaoxing also has some of the best fermented vegetables and fresh green tea leaves I have ever had in my very biased opinion.

I remember being happy – having convinced my father to make this trip and learning more about him and history that I had spent 24 years of my life entirely oblivious to.

Qiu Jin

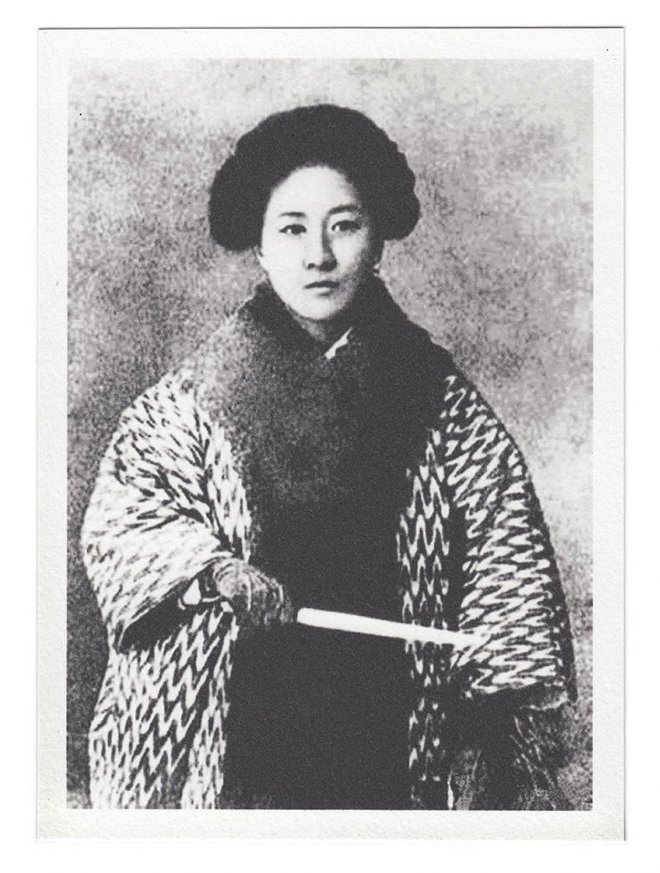

This woman needs no introduction. She is one of China’s first feminist heroes, considered China’s ‘Joan of Arc.’ Without butchering the importance of her life story (which the New York times partially covers in their Overlooked series here), she was important as she fought against the patriarchal imperialist society of the time and her own arranged marriage where her spouse subjugated her to a house wife role. She ended up cutting her hair, dressing like a man, and going to Japan to study and eventually became a revolutionary martyr. In coming back and trying to organize she ended up back in her ancestral home town of Shaoxing. She was eventually murdered (beheaded) by the Qing troops who caught up with her in Shaoxing.

Some in the west are familiar with the following stanza of her famous poem written as she was facing death:

“Autumn wind, autumn rain, fill one’s heart with melancholy.”

I want to share another poem of hers called Mistake (失题) where she drops deep metaphors of war, and the failures of masculinity. She writes in traditional five character stanzas where are deep and beyond my level of Mandarin comprehension but I’m slowly working through. Her work is truly something else.

Other than hometown, you might be wondering what my own story has to do with Qiu Jin other than the shared hometown. That is where my great-grandfather comes in and plays an interesting (and very complicated role).

My Great-Grandfather’s Parable to a Grandson He Never Met

I’ve never met my great grandfather. In fact, I only have met my own grandfather twice (once on a longer extended trip) before he passed. He had my father when he was quite old (sadly, I only realized this about two weeks back when I was doing the math based on the family tree).

My grandfather was a teacher and educator and wrote about language retention techniques (if I am not mistaken). Some of his textbooks written in the 1980s are still for sale in China., online today. Apparently he left Shaoxing and Taoyanzhen when he was 12 years old for Shanghai.

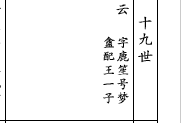

His father, my great-grandfather, was a man named Tao Yun 云 (Chinese word for ‘cloud.’) He also had two other names Lusheng 鹿笙 (Chinese word for ‘deer’) and the nickname 梦 (Chinese word for ‘dream’). I definitely got the ‘clouds’ and the ‘dream’ portion passed on to me (not so sure about the deer).

All of this was captured in Master Tao’s family tree book which I mentioned I had a digital copy of, but here is the excerpt for my great-grandfather (29th generation). We’re 31st and my future kids hopefully 32nd.

On that first trip to my ancestral hometown, Master Tao told my father that his grandfather Lusheng Tao (he called him), was quite a renowned teacher/mentor. He would teach several youth/teenagers/adolescents to read and write, the classics, and became their mentor. It appears he was a bit of a ‘behind the scenes’ guy, wasn’t considered famous but yet he was well-known in the community.

Doing some further research online, I found out he was also the teacher of one Zhang Xiyu, who also became a writer/publisher, strong feminist advocate, and later was a victim of the cultural revolution the late 1960’s. As a side note, I would love to know from others/historians/individuals located in China if he mentored and taught more students.

Another one of my great-grandfather’s students was – you guessed it – Qiu Jin. When Tao Master told my father, I was listening but my command of the language wasn’t good enough. I missed a lot of the important details. However, I did learn this one parable about what happened to my great-grandfather with respect to Qiu Jin.

When Qiu Jin fled the Qing imperial forces (as a result of her counter-revolutionary activities) she apparently landed on my great-grandfather’s door steps seeking refuge. After all, he was her mentor. I am not sure if this was just when Qiu Jin was a youth or after she escaped her abusive relationship and went to Japan – something I am eager to piece together.

Apparently my great-grandfather, looking at his wife and son at that time, decided he couldn’t do it. Harbouring a fugitive would mean that his head would also be on the cutting board. After Qiu Jin’s eventual death, it was a decision he came to highly regret. I was told by Master Tao that he eventually became mentally ill because of this regret and passed away quite young in his late 40’s.

There may be a bunch of ties that I am creating myself here – but this story and this parable speaks volumes to me. I love and have a passion for teaching, mentoring, and being a bit of a ‘behind the scenes’ fixer. I constantly worry about situations involving pitting family and public interest. I like watching those I work with elevate their careers. I am passionate about de-stigmatizing mental health issues and to see a direct family connection to the effects of the illness is eye-opening.

The most eye-opening one is to my work now as an immigration and refugee lawyer. Clients are entering my office often times seeking respite and refuge from their lives. I open doors for them and hear their stories, but there are honestly and definitely times where I have similarly regretted stepping up in difficult situations. In that sense, I empathize with the conflicts my great-grandfather have but try to will myself to step up so I do not have that regret moving forward. It is still a constant battle and I look to more courageous colleagues for some of the brilliant work they do as source of inspiration.

All in all, I feel so bonded to this great-grandfather I never met.

Full Circle – Returning with Olivia

My father passed away in early 2016. In June of that year, I went to China to pick up my then fiancee (now spouse) Olivia to bring her back to Vancouver so we could formally start our lives together here.

I wanted to show her my ancestral home as she had so graciously done for me on several occasions since we met in 2013.

We found Master Tao again and told him the unfortunate news of my father’s passing. He immediately showed us the work he had continued to do since we last saw him four years ago.

During the trip, and walking around Shaoxing, I also introduced Olivia to Qiu Jin (her statute lies around this beautiful Shaoxing lake-bend) who she read about in history books but didn’t quite relate to. She still doesn’t quite share my obsession over everything Qiu Jin, but I definitely see that strong feminist characteristic in her as well – one I have to work on elevating against my own often-bad patriarchal habits. I like to think of Olivia, who volunteers with Atira and constantly challenges toxic masculinity in environments she is in, as a Qiu Jin-like figure in my life.

That day we also returned to my great-grandfather’s house. I felt that beautiful blue ray of light seem to shine down from the heavens. The house was even more dilapidated (and now abandoned), but it still has withstood time.

The next day we met up with my father’s cousins and their extended family. It was a surprise trip – they gathered all my related cousins and they treated us to amazing home-cooked Shaoxing food. I learned that my father, without our knowledge, had kept in touch with her and supported her when she lost her own husband to illness with money. That was the kind of guy my father was – super low-key and caring to a fault.

Our Stories Matter. Take Time to Listen to Them.

Where does that leave me. Back to the start.

These are our stories. These are the stories our parents often times didn’t tell us, many times because their parents did not tell us. These are the histories that we didn’t grow up with but are slowly, with age struggling to reclaim.

In the same way your parents talk about the amazing war heroes of the time, and revolutionary business owners who were the big firsts, we try to uncover the stories of our past. These stories don’t come easy. They come scarred, broken, often times in languages we barely understand.

Yet these are our stories. Without these stories there is no us. There is no migration. There is no diaspora. There is no rich cultural “Canadian mosaic” that brings you foods and your friends. Behind this, without key decisions made at different times by different family members, we may have stayed in these villages bearing our names, never to have known Canada and this Canadian life we are so privileged and grateful to live.

I, for one, am very touched by Indigenous brothers and sisters who always start off meetings by welcoming others and channelling the ancestral spirits from the pasts. What, in our modern day, has led us to do the opposite? To stop welcoming others, and to try and ignore and or speak over the stories of others to write our truths over theirs.

Give space. Open up your minds to the fact a world outside of these columnist’s reminiscing on their 80’s tourist trips to China exists. Similarly open up your minds to the fact there are substantial populations in China who cannot share their stories or even their day-to-day truths like I can so freely do here.

While in Canada, never forget that behind each face, each building, each passport bio-data page, each mixed race individual, each dish, each piece of clothing – is a story.

We should champion each other and each other’s stories and carry on the legacies of our parents, elders, and the ancestors of the homelands of our present and past.

My pops. God rest his soul. I love this photo of him and it also scares me how I’m another 20 years from looking like this (although he was always much better looking than I am).