First of all, the intention is good. It carries out an obligation from 2015. Foreign nationals in B.C. who hold an employer-specific work permit for an employer or who are authorized to work without a permit per IRPA or IRPR now have access to foreign worker protection in the case of a real and substantial risk of physical, sexual, psychological, or financial abuse.

With stories of these abuse being well-documented, especially for low-skilled and precarious workers, providing a six-month open work permit to allow the facilitation of a new LMIA-based work permit or employer is a positive step compared to the usual, tedious and challenging process of trying to obtain a TRP inside Canada.

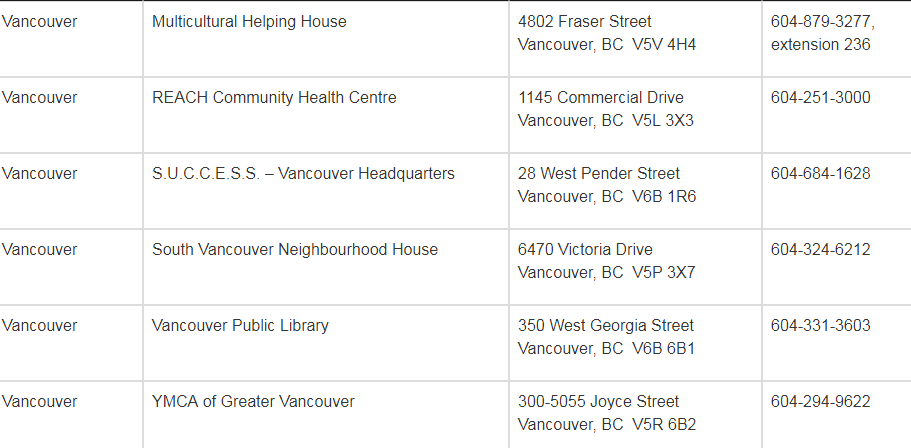

Foreign workers caught in this situation are advised to either directly contact enforcement agencies, seek the support of an approved settlement service agency (I have provided screenshots of the Vancouver ones below), or the worker can themselves approach IRCC (Vancouver) to self-report.

Interviews with IRCC can be arranged directly with the settlement service providers.

Possible Challenges

I have to admit that the first time I read the updated instructions I read them wrong. I thought that if an agency is approached by a foreign worker in an abusive situation that they should refer them to an enforcement agency as/opposed to vice-versa. It is enforcement agency that, in practice, should be referring. It would be useful to make this abundantly clear and set out much clearer guidelines than those currently in play. Having these in additional languages (especially where we know much of the abuse occurs in the ethnic economy) would be additionally helpful.

Ironically, this type of approach reminds me a lot of the recently retired conditional permanent residence (https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/archives/backgrounders-2012/backgrounder-conditional-permanent-resident-status.html) where individuals were similarly stuck between the “to report or not to report” conundrum.

Given the complexity of provincial and federal laws around employment and human rights, even the grey-ing discussions around human rights legislation (the legal responsibility of employers over their subcontractors, etc) this could create a lot of complicated legal scenarios. I wonder personally how IRCC plans to train the authorized service providers and how the authorized service providers plan to coordinate or add capacity in these areas of law prior to making the referral.

A challenging scenario could exist in the potential following fact pattern: sex worker (who does not disclose this is her line of work – and let say says he or she is in the make up/massage business) seeks help from a settlement agency. The Settlement Agency, confused by the written instruction, makes a referral to CBSA or contacts the RCMP (assuming this policy is in play) rather than IRCC. The resulting consequence is that CBSA investigates, uncovers the sex work, and issues an s.41 IRPA) non-compliance order (per s.29(2) IRPA) and a referral is made to Immigration Division before the individual is even able to contact IRCC.

A second scenario: worker is is being debt-bondaged at work and wishes to make a claim against a recruiter/agent. The individual, because of this policy, goes to IRCC Vancouver to complain. His expectation is the instructions (and the advice of his fellow workers) that there is a provision to give a work permit to abused workers. He does not realize that he has never seen a single copy of an immigration form filled out on his behalf. At the initial interview, IRCC uncovers that there was a failure to disclose a previous U.S. refusal on his work permit application or disclose a drunk driving offense. IRCC makes a referral to CBSA to begin the inadmissibility process.

Ultimately, putting such big responsibility in the hands of these authorized service providers or foreign workers who believe this is a clear-cut solution is going to be a challenge. If I was one a authorized settlement agency, I would be building a strong team of outside advisors and brushing up on the s.91 IRPA do’s and don’ts with respect to immigration advice. While they are not receiving a “fee” per se, their very funding by the government or private donors (and “payment as settlement employees” could indirectly constitute immigration advice in some circumstances. Do all these organizations now need lawyers and RCICs?

Also – what happens with this advice goes wrong? – would an individual who was removed from Canada turn back and try and sue a settlement agency. What kind of agreements or waivers are in place before the referral to IRCC (or accidentally to CBSA) is made?

What I know this move does, and as someone who has been pushing for foreign worker rights I fully support, is create the need for more expertise in the intersection between employee-side employment law, human rights, criminal law, and immigration law. Ultimately, I think we do need to create one independent think tank (be it the Migrant Workers Centre or elsewhere) to monitor this program in B.C.. Ultimately, an independent referral agency (as opposed to the settlement agencies) may be needed.

Overall Thoughts

Purely on intent, I like the idea (in theory) of providing an option for workers to safely obtain a new work permit in cases of abuse. I hope that advisors for these foreign workers do not abuse the abuse provision.

This program and it’s pilot nature (expires April 2020) is fascinating from my perspective. How does it work? Will it become a model adopted by other Provinces? Time (and trial and error) will tell.

I do hope an organization like the CBABC creates manuals and other resources to help direct what is sure to be a very complicated process.