The DADM’s Noticeable Silence: Clarifying the Human Role in the Canadian Government’s Hybrid Decision-Making Systems [Law 432.D – Op-Ed 2]

This is part 2 of a two-part series sharing Op-Eds I wrote for my Law 432.D course titled “Accountable Computer Systems.” This blog will likely go up on the course website in the near future but as I am hoping to speak to and reference things I have written for a presentations coming up, I am sharing here, first. This blog discusses the hot topic of ‘humans in the loop’ for automated decision-making systems [ADM]. As you will see from this Op-Ed, I am quite critical of our current Canadian Government self-regulatory regime’s treatment of this concept.

As a side note, there’s a fantastic new resource called TAG (Tracking Automated Government) that I would suggest those researching this space add to their bookmarks. I found it on X/Twitter through Professor Jennifer Raso’s post. For those that are also more new to the space or coming from it through immigraiton, Jennifer Raso’s research on automated decision-making, particularly in the context of administrative law and frontline decision-makers is exceptional. We are leaning on her research as we develop our own work in the immigration space.

Without further ado, here is the Op-Ed.

The DADM’s Noticeable Silence: Clarifying the Human Role in the Canadian Government’s Hybrid Decision-Making Systems[i]

Who are the humans involved in hybrid automated decision-making (“ADM”)? Are they placed into the system (or loop) to provide justification for the machine’s decisions? Are they there to assume legal liability? Or are they merely there to ensure humans still have a job to do?

Effectively regulating hybrid ADM systems requires an understanding of the various roles played by the humans in the loop and clarity as to the policymaker’s intentions when placing them there. This is the argument made by Rebecca Crootof et al. in their article, “Humans in the Loop” recently published in the Vanderbilt Law Review.[ii]

In this Op-Ed, I discuss the nine roles that humans play in hybrid decision-making loops as identified by Crootof et al. I then turn to my central focus, reviewing Canada’s Directive on Automated Decision-Making (“DADM”)[iii] for its discussion of human intervention and humans in the loop to suggest that Canada’s main Government self-regulatory AI governance tool not only falls short, but supports an approach of silence towards the role of humans in Government ADMs.

What is a Hybrid Decision-Making System? What is a Human in the Loop?

A hybrid decision-making system is one where machine and human actors interact to render a decision.[iv]

The oft-used regulatory definition of humans in the loop is “an individual who is involved in a single, particular decision made in conjunction with an algorithm.[v] Hybrid systems are purportedly differentiable from “human off the loop” systems, where the processes are entirely automated and humans have no ability to intervene in the decision.[vi]

Crootof et al. challenges the regulatory definition and understanding, labelling it as misleading as its “focus on individual decision-making obscures the role of humans everywhere in ADMs.”[vii] They suggest instead that machines themselves cannot exist or operate independent from humans and therefore that regulators must take a broader definition and framework for what constitutes a system’s tasks.[viii] Their definition concludes that each human in the loop, embedded in an organization, constitutes a “human in the loop of complex socio-technical systems for regulators to target.”[ix]

In discussing the law of the loop, Crootof et al. expresses the numerous ways in which the law requires, encourages, discourages, and even prohibits humans in the loop. [x]

Crootof et al. then labels the MABA-MABA (Men Are Better At, Machines Are Better At) trap,[xi] a common policymaker position that erroneously assumes the best of both worlds in the division of roles between humans and machines, without consideration how they can also amplify each other’s weaknesses.[xii] Crootof et al. finds that the myopic MABA-MABA “obscures the larger, more important regulatory question animating calls to retain human involvement in decision-making.”

As Crootof et al. summarizes:

“Namely, what do we want humans in the loop to do? If we don’t know what the human is intended to do, it’s impossible to assess whether a human is improving a system’s performance or whether regulation has accomplished its goals by adding a human”[xiii]

Crootof et al.’s Nine Roles for Humans in the Loop and Recommendations for Policymakers

Crootof sets out nine, non-exhaustive but illustrative roles for humans in the loop. These roles are: (1) corrective; (2) resilience; (3) justificatory; (4) dignitary; (5) accountability; (6) Stand-In; (7) Friction; (8) Warm-Body; and (9) Interface.[xiv] For ease of summary, they have been briefly described in a table attached as an appendix to this Op-Ed.

Crootof et al. discusses how these nine roles are not mutually exclusive and indeed humans can play many of them at the same time.[xv]

One of Crootof et al.’s three main recommendations is that policymakers should be intentional and clear about what roles the humans in the loop serve.[xvi] In another recommendation they suggest that the context matters with respect to the role’s complexity, the aims of regulators, and the ability to regulate ADMs only when those complex roles are known.[xvii]

Applying this to the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (as it then was[xviii]) [“EU AI Act”], Crootof et al. is critical of how the Act separates the human roles of providers and users, leaving nobody responsible for the human-machine system as a whole.[xix] Crootof et al. ultimately highlights a core challenge of the EU AI Act and other laws – how to “verify and validate that the human is accomplishing the desired goals” especially in light of the EU AI Act’s vague goals.

Having briefly summarized Crootof et al.’s position, the remainder of this Op-Ed ties together a key Canadian regulatory framework, the DADM’s, silence around this question of the human role that Crootof et al. raises.

The Missing Humans in the Loop in the Directive on Automated Decision-Making and Algorithmic Impact Assessment Process

Directive on Automated Decision-Making

Canada’s DADM and its companion tool, the Algorithmic Impact Assessment (“AIA”), are soft-law[xx] policies aimed at ensuring that “automated decision-making systems are deployed in a manner that reduces risks to clients, federal institutions and Canadian Society and leads to more efficient, accurate, and interpretable decision made pursuant to Canadian law.”[xxi]

One of the areas addressed in both the DADM and AIA is that of human intervention in Canadian Government ADMs. The DADM states:[xxii]

Ensuring human intervention

6.3.11

Ensuring that the automated decision system allows for human intervention, when appropriate, as prescribed in Appendix C.

6.3.12

Obtaining the appropriate level of approvals prior to the production of an automated decision system, as prescribed in Appendix C.

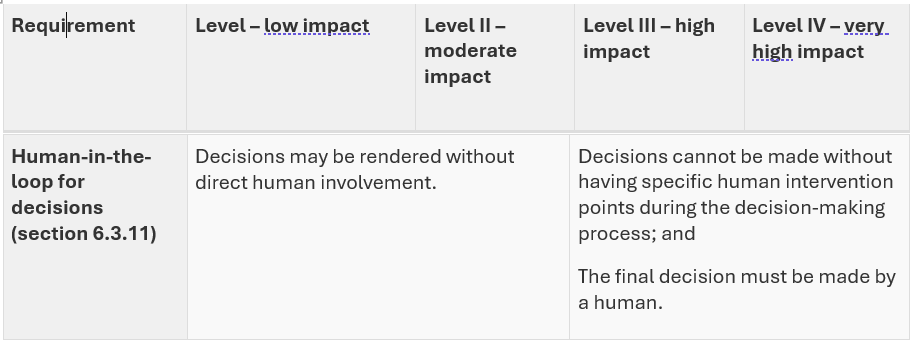

Per Appendix C of the DADM, the requirement for a human in the loop depends on the self-assessed impact level scoring system to the AIA by the agency itself. For level 1 and 2 (low and moderate impact)[xxiii] projects, there is no requirement for a human in the loop, let alone any explanation of the human intervention points (see table below extracted from the DADM).

I would argue that to avoid explaining further about human intervention, which would then engage explaining the role of the humans in making the decision, it is easier for the agency to self-assess (score) a project as one of low to moderate impact. The AIA creates limited barriers nor a non-arms length review mechanism to prevent an agency strategically self-scoring a project below the high impact threshold.[xxiv]

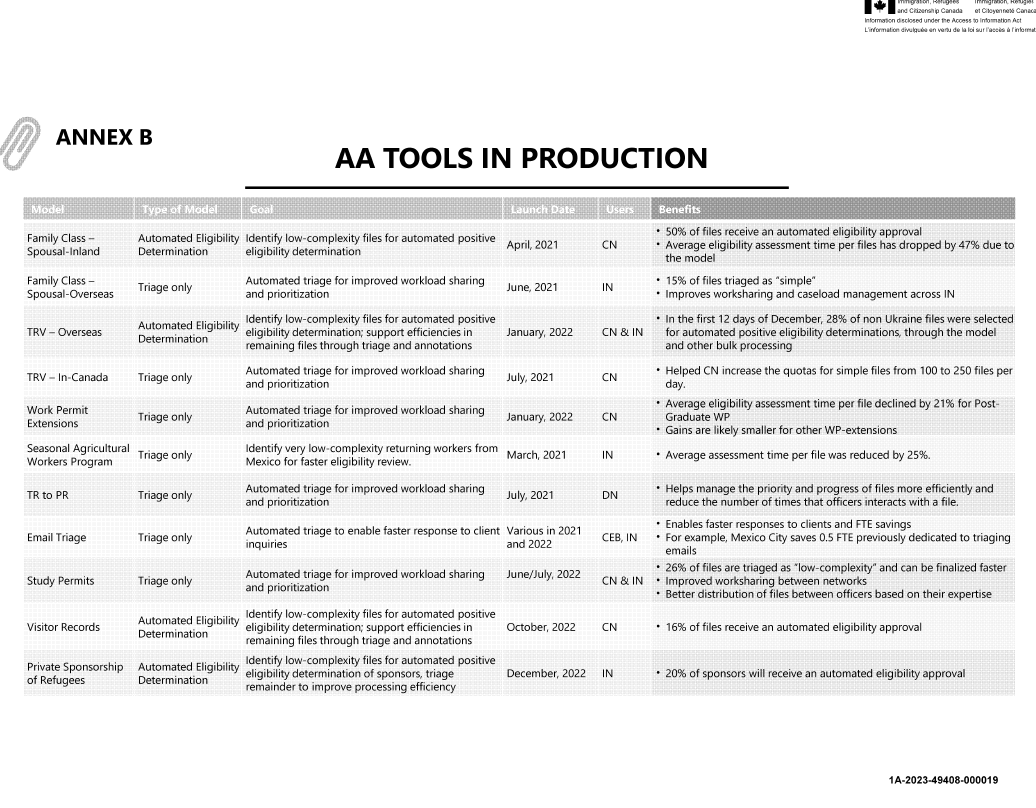

Looking at the published AIAs themselves, this concern of the agency being able to avoid discussing the human in the loop appears to play out in practice.[xxv] Of the fifteen published AIAs, fourteen of them are self-declared as moderate impact with only one declared as little-to-no impact. Yet, these AIAs are situated in high-impact areas such as mental health benefits, access to information, and immigration.[xxvi] Each of the AIAs contain the same standard language terminology that a human in the loop is not required.[xxvii]

In the AIA for the Advanced Analytics Triage of Overseas Temporary Resident Visa Applications, for example, IRCC further rationalizes that “All applications are subject to review by an IRCC officer for admissibility and final decision on the application.”[xxviii] This seems to engage that a human officer plays a corrective role, but this not explicitly spelled out. Indeed, it is open to contestation from critics who see the Officer role as more as a rubber-stamp (dignitary) role subject to the influence of automation bias.[xxix]

Recommendation: Requiring Policymakers to Disclose and Discuss the Role of the Humans in the Loop

While I have fundamental concerns with the DADM itself lacking any regulatory teeth, lacking the input of public stakeholders through a comment and due process challenge period,[xxx] and driven by efficiency interests,[xxxi] I will set aside those concerns for a tangible recommendation for the current DADM and AIA process.[xxxii]

I would suggest that beyond the question around impact, in all cases of hybrid systems where a human will be involved in ADMs, there needs to be a detailed explanation provided by the policymaker of what roles these humans will play. While I am not naïve to the fact that policymakers will not proactively admit to engaging a “warm body” or “stand-in” human in the loop, it at least starts a shared dialogue and puts some onus on the policymaker to both consider proving, but also disproving a particular role that it may be assigning.

The specific recommendation I have is to require as part of an AIA, a detailed human capital/resources plan that requires the Government agency to identify and explain the roles of the humans in the entire ADM lifecycle, from initiation to completion.

This idea also seems consistent with best practices in our key neighbouring jurisdiction, the United States. On 28 March 2024, a U.S. Presidential Memorandum aimed at Federal Agencies titled […]