Canada’s New Electronic Travel Authorization Regime: 5 Things You May Not Have Known

Because the actual requirement to hold an Electronic Travel Authorization (eTA) does not kick in until March 2016, the regime has been understudied and largely unreported outside of the immigration legal community.

On the surface, the new eTA requirement conceptually seems quite simple. Up to now, those exempt from the temporary resident visa requirement process did not undergo any prior screening or vetting. Decisions were made solely at the port of entry and concurrently Canada’s border/immigration system was susceptible to allowing in visitors, who had not made prior applications to Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) and who are ultimately inadmissible, into Canada.

Importantly, Canada made some commitments in the Canada–U.S. Beyond the Border Action Plan several years ago where they pledged to introduce an eTA regime. They were bound by those commitments to introduce the regime.

I want to highlight in this piece, five things you might not know about the eTA regime.

By the way, I will not go through a comprehensive review of the regime. For those who want to read more about the policy changes in general, check out CIC’s Program Delivery Update for August 1, 2015 and the text of new Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (IRPR) via the Part 2 – Gazette in April of this year. Check out also my colleague Steve Meurren’s post for a summary of the new regime.

#1 – The eTA now allows for visa-exempt visitors to Canada to be issued removal orders from outside Canada. Until that removal order is enforced, the visitor will not get an eTA and not be allowed to come to Canada.

This authority is created by by subsection 240(2) of IRPR which states (emphasis added):

240. (1) A removal order against a foreign national, whether it is enforced by voluntary compliance or by the Minister, is enforced when the foreign national

. . . .

When removal order is enforced by officer outside Canada

(2) If a foreign national against whom a removal order has not been enforced is applying outside Canada for a visa, an authorization to return to Canada or an electronic travel authorization, an officer shall enforce the order if, following an examination, the foreign national establishes that

(a) they are the person described in the order;

(b) they have been lawfully admitted to the country in which they are physically present at the time that the application is made; and

(c) they are not inadmissible on grounds of security, violating human or international rights, serious criminality or organized criminality.

And until that removal order is enforced (i.e. they meet the above requirements), s.25.2 of IRPR applies:

Electronic travel authorization not to be issued

25.2 An electronic travel authorization shall not be issued to a foreign national who is subject to an unenforced removal order.

#2 Cancelling an eTA (at least from a legal perspective) is not as easy as CIC makes it seem (from a policy perspective).

The intersection between policy and law always play an interesting role in Canadian immigration law. As the Federal Courts have made clear on several occasions, online instruction guides, processing manuals, operational bulletins (which now can be extended to include program delivery updates) do not constitute law.

Often times CIC will provide instructions that summarize the law without providing its full details or make recommendations that aren’t legal policy (e.g. when they tell applicants they should apply for extensions 30 days before expiry for several programs, when often times doing may hurt their implied status).

CIC writes on their webpage regarding eTAs:

For how long is an eTA valid?

Section 12.05 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations indicates that an eTA is valid for five years or until the applicant’s passport expires, whichever occurs sooner.

Section 12.06 of the Regulations indicates that an eTA can be cancelled by a designated officer. Once cancelled, an eTA is no longer valid.

While this statement is not incorrect per-se- it omits a few important details.

Cancellation

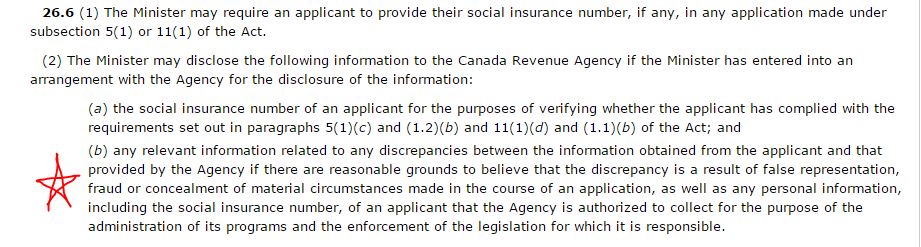

12.06 An officer may cancel an electronic travel authorization that was issued to a foreign national if

-

(a) the officer determines that the foreign national is inadmissible; or

-

(b) the foreign national is the subject of a declaration made under subsection 22.1(1) of the Act.

Subsection 22,.1(1) of the Act (Immigration and Refugee Protection Act) is an interesting one.

This section allows the Minister, on his or her own initiative, to declare that a foreign national cannot be come a temporary resident for a period of three years, justified by “public policy considerations.” The underlying provisions has been in force since August 2013 but it appears no Federal Court jurisprudence (at least none that I could find) talk about this provision. To me it is a very discretionary provisions.

Could we see an increase of cancellations of eTAs on s.22.1(1) IRPA grounds where inadmissibility has not yet been made out but there is some concern about the individual’s background? I certainly think so.

#3 – Adverse Information on your immigration file may mean your eTAs might take a while.

CIC has made available by way its most recent program delivery update, updated instructions for how to assess adverse information on file for an eTA applicant.

CIC writes (emphasis in original and added):

If the applicant previously applied for entry to Canada (either through a CIC program or through the CBSA at the port of entry), or if they are already known to CIC (through intelligence, for example), and if there is adverse information on file for the applicant, it will be uncovered through the automated eTA screening process, which will cause the application to be referred for manual review.

Officers should consider:

- Did the adverse information result in a previous refusal?

- If so:

- What is the full story behind the refusal? Look at the case notes to fully understand the reason for the previous refusal. It is not sufficient to only look at the refusal ground(s).

- Was the applicant previously refused because they did not meet the specific needs of the category to which they were applying? For example, if they were refused a work permit because they did not provide a labour market impact assessment, would this impact their eligibility to come to Canada as a visitor?

- Have their circumstances changed since the refusal? Is this still a concern?

- Has the applicant received an approval between the time of their eTA application and the adverse information on file? Note that the automated eTA screening process will not take this into account when determining if a case should be referred for manual review.

- If not:

- What type of adverse information is on file?

- How long ago was it entered?

- Has the applicant received an approval between the time of their eTA application and the adverse information on file? Note that the automated eTA screening process will not take this into account when determining if a case should be referred for manual review.

An officer must be satisfied that an applicant is not inadmissible to Canada under A34 to 40 prior to issuing an eTA. Officers initiate and conduct admissibility activities as needed. This may include screening requests to partners, criminal record checks, info sharing, medical exams and misrepresentation activities.

I find CIC’s example of applying for a work permit without an LMIA kind of curious, as not meeting program requirements does not directly lead to an inadmissibility. However, it appears to suggest that for these type of cases, a procedural fairness letter may be sent to eTA applicants asking them to “explain the circumstances”, with the ultimate fear being that an applicant is attempting to enter Canada to work without authorization.

What this all means, is an Applicant needs to be very careful with misrepresentation (a topic I have written about quite extensively, so see previous posts!).

#4 Permanent Resident Problems are Coming

Strategically for a permanent resident, there may have been reasons in the past to enter Canada on a separate passport or travel document (particularly if their permanent resident card had expired or was lost and/or they no longer met the residency requirement).

eTAs effectively end that practice and create an added barrier – the e-relinquishment process.

CIC writes in their website section titled “Manual processing Electronic Travel Authorization (eTA) applications“) (emphasis added):

Officers should consider:

- Based on case history, is the applicant indeed a permanent resident?

- Based on case history, has the applicant renounced their permanent resident status? Often, even though a person has renounced their status, their GCMS profile still shows them as a permanent resident.

Procedure

Level 1 decision-makers at the OSC will query for these applications by performing a search in “IMM activities, Auto Searches.” The “Activity” will be “Derogatory information,” the “Sub-activity” will be “Client Derogatory Information,” and the “Status” will be “Review Required.”

If the applicant is a permanent resident and has not already gone through the formal process of relinquishing their status, they should be contacted to determine whether they would like to voluntarily relinquish their status

-

If the applicant does not wish to relinquish:

- The officer must withdraw the application

- Advise the applicant that they will need to get an appropriate travel document that demonstrates that they are a permanent resident, which may necessitate a determination of their status (PDF, 665.91 KB)

-

If the applicant would like to relinquish:

-

-

Once they have done so, and assuming they are otherwise admissible, the officer may issue the eTA

-

Again, expect this new eTA to increase the number of residency determinations and will likely trickle through to more appeals at the Immigration Appeal Division.

#5 Interactive Advance Passenger Information (IAPI) and Carrier Messenger Requirements (CMR) make Airline Staff the Front-Line Messengers for the new eTA program

An Applicant holds a valid eTA and is now booking a plane ticket. Now what?

There is a whole process that runs in the backdrop between commercial Airline Carriers and Canada Border Services Agency to inform them of who is on the plane that will be arriving in Canada. A lot of the front end information sharing will essentially begin with you entering your name into a flight reservation system to buy tickets all the way until you arrive in […]