Recently, I have had a major increase in misrepresentation consultations and other related issues with one common starting point: incorrect work/personal history that either Canadian immigration has found or will eventually find out about.

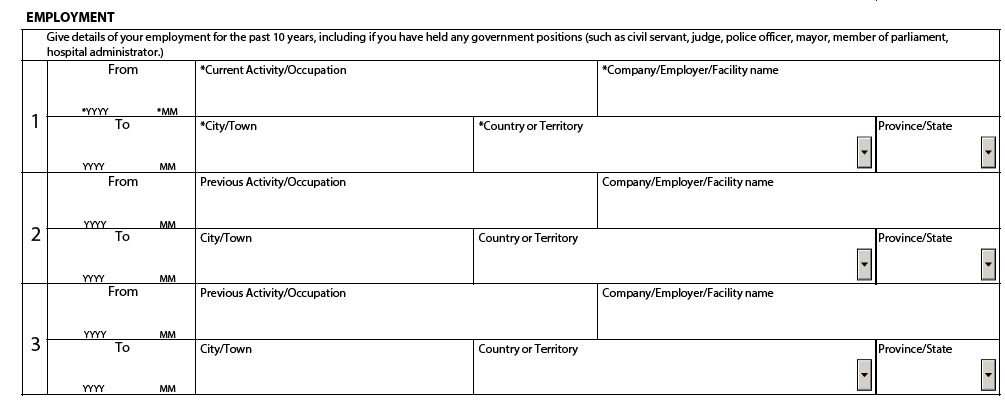

There are several forms that canvass work/personal history. This ranges from initial application forms (IMM 1294, IMM 1295, etc.) to the IMM 5257E Application for a Temporary Resident Visa Forms, to the dreaded IMM 5669 – Schedule A.

Each form (and accompanying instructions) often ask for the materials a different way. Some forms ask for only employment history, whereas others as for a full ten-year history. Complexities also arise when certain visa offices want a full personal history starting from the age of 18, but do not make these instructions apparent at the outset, requiring them later in request letters.

What often happens is a hot mess of unclear work dates, forgotten travels, mistaken residences, and IRCC analyzing all of these for possibly material misrepresentations that may impact officer assessment.

To make things even more complicated, misrepresentations can extend to past applications, even if it is attempted to be corrected. Memories are imperfect, what is required to be disclosed is confusing, and unfortunately perfectly innocent applicants can make devastating mistakes.

While there are some positive trends in judicial interpretation, the law around misrepresentation in Canada is harsh: a five-year bar from Canada (and from applying for permanent residence) regardless of the intent of the error or omission, and a thin-exception for innocent misrepresentation.

In this post, I look at three common mistakes I see applicants (and their representatives make) and how to avoid them. I will close with a new approach I am taking to documenting work history for my clients on temporary resident applications.

Mistake 1: Omitting Material Personal History/Blurring Dates Together

There are several sub-mistakes under this category:

[1] Applicants often include only their last position held, rather than to breakdown the various positions within a company

This one may seem innocuous now, but on a PR application or when facing an employer’s reference letter that paints a different picture this could be an issue. Often times these dates are also contradicted by public information you may have about yourself online, such as your LinkedIn profile or a biography you hastily submitted to a third-party who has posted it online.

Visa Offices also have many internal tools at their fingertips. For example, for China, they have access to a quite comprehensive ‘legal persons’ registry for businesses. Particularly for entrepreneurs or businesspersons who own multiple businesses, failures to disclose one (even if it is unclear whether it constitutes employment or ownership) could constitute misrepresentation. This was the fact pattern in the Federal Court’s decision in Sun v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2019 FC 824 (CanLII).

My rule of thumb is to over-disclose rather than under-disclose if there are no inadmissibility risks to the additional details being disclosed and it may set forward a good groundwork to get ahead of a potential issue or pave the way for a future application. If your disclosure of the item could affect your eligibility, consider whether applying on misrepresented information could come back to haunt you in the future.

Yet, many times the information being omitted is not itself going to change the decision of the Officer, but the very omission of the information could impact the Officer’s processing or review of the requirements, which could make it a material misrepresentation.

[2] Applicants often don’t include periods of unemployment, self-employment, and educational pursuits

Often times Applicants only provide just the formal work/employment history and forget to include the personal history. Again, the forms make it a bit confusing. In the description of the form, it asks for employment history, but in the fine print it may say to include periods of unemployment or leave no gaps. Another challenging aspect is that certain applications (co-op work permits and post-graduate work permits) do not actually require full disclosure of work history, whereas other applications (temporary resident visas inside Canada) do. We play it safe by including a running 10-year history for all applicants, regardless of it is a requirement.

This often rears its head as an issue when a visa is refused for lack of continuous study or lack of relevant employment history demonstrating there are opportunities in the country of residence. When it is only indicated that one is ‘unemployed’, the literal interpretation the Officer will take is that you are at home doing nothing. Trying to start up your own business or taking pre-requisite courses for a formal program of study, is not sitting home doing nothing and may be very material. Failure to include this initially could create discrepancies later (see mistake 3 below).

[3] Applicants do not disclose sufficient details in the personal histories

In my work often reviewing materials for refused clients, often who applied the first time themselves or less competent counsel, there are common themes.

Rather than put detailed descriptions of position or title – words such as “employee” or “management” or “police officer” are used. Alternatively, when discussing employment rather than put the company or school name, answers such as “restaurant business” or “self-employed” or put down. Immigration Officers may want to conduct an inadmissibility inquiry into your former work place, or verify that you indeed worked for said employer or that such a company/organization exists.

If there is an admissibility concern or clarification to be made, make sure to make it on a letter of explanation or clarify (see attached). Too often I see clarifying explanation missing until after a Procedural Fairness Letter (PFL) is received. This is often times far too late in the game.

Mistake 2: Not Correcting the Mistake When IRCC Gives You a Chance (Requests vs. PFLs)

When IRCC notices an inconsistency (and depending on what visa office and what type of application), there may be the opportunity provided to fix an inconsistency. Commonly, especially if a misrepresentation is not apparent on the surface, a request letter will be issued offering an opportunity to clarify or seeking further information. `

The tendency with request letters, I find, is to blindly try and answer them as soon as possible. Applicants immediately take a defensive position, without thinking at that stage that the request letter could be the set up for an A16(1) IRPA (failure to truthfully provided requested documents) or worse yet, an A40 IRPA (misrepresentation) refusal. Given the withdrawal of an application is unlikely to be granted after a PFL is issued and the leg work is all but done at that stage, it is as the request letter stage that clarifications need to be sought and legal arguments made.

Repeated errors in providing accurate information or misunderstanding request letters could later lead to further challenges arguing innocent misrepresentation or seeking discretion later on in the process.

Mistake 3: Not Keeping Adequate Records and Inconsistencies Between Applications

Visa Offices such as those in India (especially Delhi and Chandigarh) and China (Beijing) now utilize artificial intelligence tools that will be able to spot an inconsistency instantaneously.

Before submitting an application, if possible, compare your forms with previous forms submitted. Better yet, request or obtain (by access to information) a copy of all final forms before a representative submits any application for you.

Another discrepancy I see is with address history, travel history, and work history on forms. Where these do not align, and particularly when it comes to permanent residence applications that look into where work was performed and where the Applicant was located, and whether or not the claimed work matches with past records – this becomes ever so important. Virtual work or work through multiple client sites is becoming more popular, and failure to properly document this in respective applications may complicate things when permanent residence rolls around.

My New Approach: Focusing on Forms First, and then Attachments

In the past, a move I did (and one I know many counsel mirror) is to put “please see attached” on the work history sections or personal history sections of some validated temporary resident forms and then add a work document. This option will not be available with the new online temporary resident portal, which like Express Entry do not allow you to move on to the next page until there are no gaps. In the interim, what I am suggesting with the validated forms is still to list as much as possible on the form and then add ‘see attached’ on the final line before continuing.

The reason for this is that IRCC has been focusing on auto-populating systems like Chinook that appear to extract information directly from forms into their internal processing system. I am worried that my attached table found at the back of my rep’s submission letter is missed by a processing agent or in review. We know increasingly that the Officers are only accessing the information extracted for their review and are under a major time crunch. This little tip might help practitioners and self-reps.

Some Positive News: Court Critical on IRCC’s Need for a Materiality Analysis of Misrepresentation

While misrepresentation is often a death trap for an immigration application, the Federal Court has recently been pushing back on the tendency of IRCC to equate a mistake as misrepresentation, without an analysis of materiality.

In Alves v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2021 FC 716 (CanLII), Justice Manson allowed a judicial review after finding that an Officer’s finding of misrepresentation was unreasonable. The Applicant disclosed one of his previous refusals to the United States, but had omitted an earlier one.

Justice Manson writes:

[19] However, an officer must consider the totality of the evidence before the decision maker (Koo v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2008 FC 931 at para 23). The Officer, in this case, failed to recognize the potential significance of the mitigating evidence, as it relates to the finding of misrepresentation without meaningfully coming to grips with the facts before the Officer. Instead, the Officer broadly found that the Applicant had misrepresented. In the Global Case Management System, on December 31, 2019, the Officer further describes that the Applicant’s explanations in response to the procedural fairness letter were unreasonable, dismissing the evidence without due consideration. This assessment falls short of establishing a finding of misrepresentation on the balance of probabilities, given the contradictory evidence was apparently readily dismissed.

[20] While the Applicant may have failed to provide sufficient specificity, she correctly answered the relevant question in the affirmative and referenced her adverse immigration status in the United States. The Officer failed to take into account this relevant evidence. On this basis, the Decision lacks the requisite degree of justification, transparency and intelligibility (Vavilov, above at para 86). The Decision simply does not

“add up”.

[21] Further, it is unclear how the Officer came to the conclusion that the misrepresentation was material. Notably, whether the misrepresentation was sufficiently important to affect the process, foreclosing or averting further inquiries (Oloumi at para 25; Li v Canada (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship), 2018 FC 87 at para 13). The Applicant answered

“yes”to the single background declaration question, which asks whether the Applicant has adverse immigration history and disclosed her most recent refusal from the United States, which is connected to the 2015 events in question. It appears in such a case that the disclosure in question prompted the appropriate inquiries, as anticipated by the Applicant. The evidence does not justify the Officer’s finding that the misrepresentation was material in this case.(emphasis added)

However, in the context of work and personal history – especially given these two are often material to the analysis of whether one meets the criteria for a permanent resident program or a work permit, or are inadmissible for security or human rights violations. In these cases it may be more difficult to establish that omission was non-material and IRCC will not need to work too hard to establish materiality.