When new changes occur to IRCC’s Guidelines and programs it can take several forms and be communicated to applicants in several ways.

Of those communication methods, we see most often Program Delivery Updates, Notices, and new Operational Bulletins. Legislative changes are often announced through Ministerial Instruction and the GOC’s Canada Gazette.

Most of these changes are relatively well-documented and updated quite quickly after the change is announced. On a side note, I would suggest the Program Delivery Updates could be a little more clearer, as even for myself, who read them religiously. Some of the changes IRCC introduced are hard to track in the text.

The one major gap that IRCC has is in updating it’s new instruction guides, new visa-office specific guides, and new forms. Recently, we’ve seen several of these changes occur without corresponding changes to the website indicating that the document has been updated. In the case of some of the forms, they have even been backdated to reflect when the document was originally created rather than when it was made public. All of this creates confusion, and for IRCC likely more litigation.

Below are just a few examples.

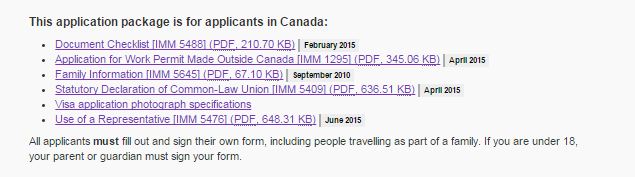

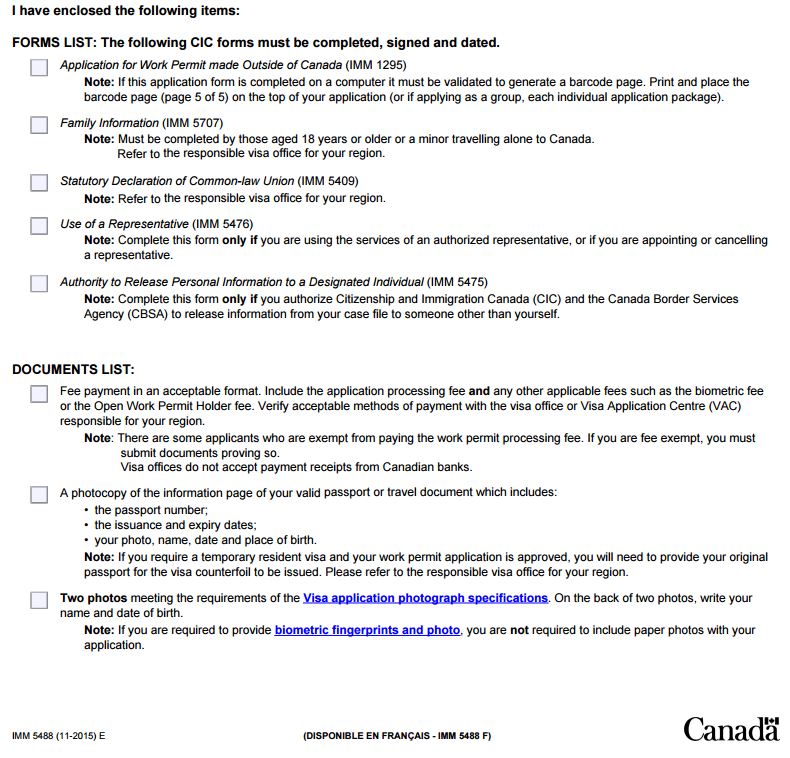

1) The Document Checklist (IMM 5488) for Work Permit Outside Canada is dated February 2015 as per CIC’s website.

The Actual Document is dated November 2015.

In reality, the document was uploaded sometime late December 2015/early January 2016.

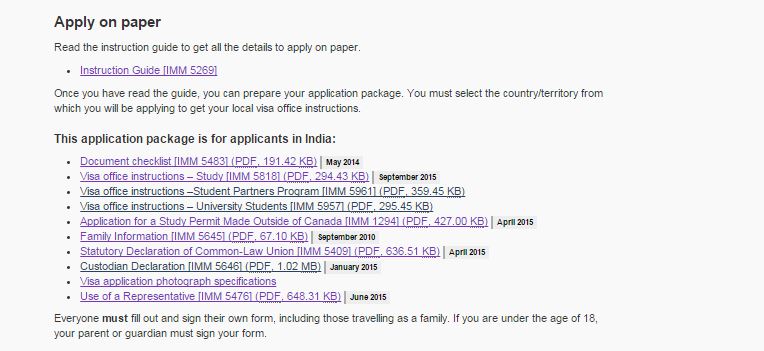

2) Below is the most recent Study Permit Visa Specific Instruction Guide for Applicants from India

The CIC Website displays the most recent document as being September 2015.

Implications

For Applicants, the risk with submitting outdated forms is that the Applicants may be refused and or returned for incompleteness. This is particularly true when the document checklist or forms contain new fields that are not in the old versions. CIC may offer some sort of “grace period” but this is solely discretionary and as far as I am aware there is no CIC policy on the reasonable transition period for which they will accept old versions in lieu of the updated versions.

Possible IRCC Solution – Updates Database

I understand that IRCC is working on several strategies in support of digitizing their program integrity and integrating their various networks.

With all these changes sure to occur there needs to be some adequate (publicly available) tracking of all these changes. In fact, anytime a webpage or form changes, it should trigger an update.

This page can also serve as an amalgamation of all the changes occurring across all of IRCC’s platforms.

This is important for several reasons. In the post-Dunsmuir reasonableness era, applicants are more hardpressed to try and show an Officer’s decision was made unreasonably on the merits, particularly when they are owed deference and their judgment falls within the reasonable realm of possibilities. Courts are still eager to point out situations where they may have made different decisions had they assessed the case, but maintain their role is not to readjudicate the decision but rather review the Officer’s decision-making process.

Procedural fairness issues, which (in most contexts) do not require that the Court provide any deference to the decision-maker are stronger in the context of litigation. I believe you will see increasingly applicants attempting to show that the IRCC guidelines created legitimate expectations (i.e. that IRCC;s website showed the latest updated version that the applicant had legitimate reason to rely on). For a good case about the doctrine of legitimate expectations read Lebel J’s unanimous judgment in Agraia v. Canada (Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness) 2013 FC.

Also, several of recent CIC/IRCC Guidlines, the IP 8 – Spouse or Common Law in Canada Class at 17.4 (pg 62) and OB-265A – January 8, 2016 Email Communication with Clients, seem to contemplate an increase of Reconsideration Requests from Applicants with refused applications. This may be a broader trend that IRCC is taking towards reducing the high-cost of Federal Court litigation.

Furthermore, there is case law on the procedural duty of fairness owed to applicants to consider new documents where the change in requirements does not arise directly from legislation or regulations and instead a product of IRCC policy.

In Noor v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) 2011 FC 308, an Indian Permanent Resident applicant was refused for failing to include an item in the Visa-Office specific instructions for permanent residence applications from India. The instruction guide had changed in the middle of application processing and asides from the new document having changed dates, there was no indication provided by IRCC to the Applicant of the change.

In assessing whether a breach of procedural fairness had arisen in the Officer failing to consider additional documentation the Applicant submitted in his Reconsideration Request to try and rectify the error. Scott J writes (emphasis added):

B. Was there a breach of procedural fairness?

30 The Applicant notes that his own failure to submit the correct documents on his original application resulted from the very recent changes to the Visa Office-Specific Instructions posted online. He notes that this was a dramatic and important change, not widely publicized but rather buried in an otherwise unmodified instruction kit. He further points out that the Visa Officer was clearly aware that he was using the old kit, as he attached a copy of its checklist with his application, but that rather than give him the opportunity to correct his application, his application was rejected. The Applicant acknowledges that the Visa Officer may not always be under an obligation to inform an applicant of the deficiencies of his application, but argues that in the unique circumstances of this case, procedural fairness required that he be given some kind of opportunity to provide the missing documents, in view of the recent modification, which was only ascertainable by reading the extra bullet point. The Applicant notes the Officer’s explanation that the refusal to rectify his file came about because of the “reasonable expectation” that he check the new instructions, but argues that this was in fact unreasonable in the circumstances of this case.

31 The Applicant notes that there is no duty of fairness case that is directly on point. However, he cites from Athar v. Canada (MCI), 2007 FC 177, which canvassed jurisprudence on cases involving permanent residence applicants facing credibility concerns at hearings, and whether they should be informed of the deficiencies of their applications. At para. 17 of Athar:

- [There] may still be a duty on the part of a Visa Officer, in certain situations, to provide an applicant with the opportunity to respond to his or her concerns, in accordance with the rules of procedural fairness.

32 Athar also cites Hassani v. Canada (MCI), 2006 FC 1283, where Justice Mosley wrote:

- [It] is clear that where a concern arises directly from the requirements of the legislation or related regulations, a Visa Office will not be under a duty to provide an opportunity for the applicant to address his or her concerns. Where however the issue is not one that arises in this context, such a duty may arise.

33 The Applicant argues that the requirements in this case did not arise from the Act or the regulations, which do not lay out any documentation requirements, but rather from a change in a specific policy. It would have been easy to give the Applicant the opportunity to rectify his application, especially as the Visa Officer was aware that he used the incorrect kit, and this would have satisfied the duty of fairness in the unique circumstances of this case.

34 The Respondent counters that in the Visa Officer decisions, the content of the duty of fairness when determining visa applications has been held to be towards the lower end of the range, as per Patel v. Canada (MCI), 2002 FCA 55, para 10, and Malik, para 29. Given that the Applicant must establish certain criteria to succeed in his application, the Respondent argues that the Applicant should assume that the Visa Officer’s concerns will arise directly from the Act and the regulations, and the onus remains on him to provide the correct documentation. Here, the Applicant was asked to submit a full application, including the documents listed in the Visa Office-Specific Instructions. The Respondent argues that the Applicant was specifically directed to use the 04-2009 Kit, and that this was available five (5) months prior to the submission of his full application.

35 The Applicant is correct in pointing out that the documentation requirements are not set out in the Act or the regulations, but only in the online instruction kit. While this Court did not find that Malik and Nouranidoust could support the Applicant’s first issue, the comments made by the judges in those cases (advising that new documentation ought to be allowed in certain cases) is persuasive in the context of the duty of fairness owed to someone in the Applicant’s distinct situation. It was clear to the Visa Officer that the Applicant was using the older kit, which had recently been changed, yet he was afforded no opportunity to rectify this simple error. Furthermore, the Respondent is incorrect in stating that the Applicant was specifically advised to use the 04-2009 Kit. The letter sent to the Applicant on July 28 (found as Exhibit B to the Applicant’s affidavit, Applicant’s Record p 31) simply directs him to the CIC website for “Visa office-specific forms and a list of supporting documents require by the Visa office”. There is no specific indication at all that these requirements would have changed.

36 The Applicant clearly stated in his request for reconsideration that he had used the old instruction kit. The Court finds that this should have been clear to the Officer making the initial decision, as a copy of the kit’s checklist was attached. Even with a low duty of fairness, in the specific circumstances of this case, that duty required the Visa Officer to consider the new documents.

This case is by no-means precedential and has been distinguished in a few cases since. However, in my mind it creates enough of a model for a litigant to pursue recourse where guidelines are outdated and the applicant’s efforts to request reconsideration are refused without analysis.

If IRCC were to create a central, publicly available database of changes and direct Applicants on all refusal letters to the database this could seek to remedy procedural fairness issue concerns.

At the very least, it would certainly drive down the cost of litigation, encourage more collaborative dispute resolutions and overall is good to encourage more access to justice for self-representing applicants.