A portion of this article is a modified summary of a presentation done in October 2019 where my colleague Karen Jantzen (Law Student, Allard Law School at UBC) and I presented on ‘Privigration’. Those that are interested are recommended to purchase the webinar. We’re still looking into this area of the law and refining as we go!

Personal information banks (PIBs) describe the personal information that a government institution controls and uses for administrative purposes in a program or activity. The description includes the procedure for collection, use, disclosure, and retention or disposal of the personal information. They can also provide specific instructions for individuals requesting information stored in the bank.

Personal Information Banks or PIBs are the central go-between/foreground in an area of law I have called ‘Privigration‘ – where Privacy and Immigration Law meet.

In our information-sharing/AI generation, personal information becomes the central currency. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner (“”OPC”), as it stands, does not offer much by way of enforcement or remedy. Short of Privacy Commissioner investigations that can only report on wrongdoing but not institute wrist slaps, it is Government themselves (and their various agencies) that must regulate how they share information between each other in a manner that is consistent with the Privacy Act (see s.35 here). Meanwhile, legislative purposes (see various Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement(s)) and wording of legal provisions are providing even more expanded purposes to facilitate the sharing of private information of applicants without the need for consent or where individuals may not be aware of their prior consent.

It is important to start this multi-blog conversation by looking at Personal Information banks as the central vehicle by which information goes from one government body to another. With these different government bodies having information sharing agreements with other country, not only is this inside Canada but outside to other Government bodies.

What is Personal Information?

Personal information is defined by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada as “data about an ‘identifiable individual.’ It is information that on its own or combined with other pieces of data, can identify you as an individual.” It can be recorded in any form, and includes information about race, ethnic origin, religion, marital status, age, education, medical, employment, criminal history, financial transactions in which the individual was involved, identifying number or symbol assigned to the person, address, fingerprints, blood type, personal opinions or views of the individual, or of someone else about the individual, confidential correspondence with the government. Excludes info about the work of government employee or contracted worker, as well as someone who has been dead for 20 years.

Fundamental premise or values and principles is that PI shall not be shared with third parties without the consent of individuals to whom the information relates. This is because the sharing of personal information by government agencies with third parties could infringe on the personal rights, freedoms and liberties that exist in Canada today. However, there are a number of exemptions that allow government agencies to use personal information, without the individual’s consent, in order to efficiently administer programs, enforce the law, act to protect the safety of Canada and contribute to international peace and good order

Differing Definitions of PIBs

CBSA defines Personal Information Banks (PIBs) as:

Standard personal information banks: these are descriptions of personal information contained in records, and collected and used to support internal services.

It is to be noted that there is a hyperlink to the more comprehensive Treasury Board link below.

IRCC provides a little more detail but without a link to the standard personal information banks:

Personal information banks (PIBs) are descriptions of personal information under the control of a government institution that is organized and retrievable by an individual’s name or by a number, symbol or other element that identifies that individual. The personal information described in a PIB has been used, is being used or is available for an administrative purpose. The PIB describes how personal information is collected, used, disclosed, retained and/or disposed of in the administration of a government institution’s program or activity.

The Treasury Board of Canada provides the most comprehensive definition. Before we discuss this definition, we should look a bit into the Treasury Board of Canada.

The Treasury Board of Canada advises and makes recommendations on how government money is spent on programs and services. In its commitment to open government, to ensure tax dollars are spent effectively, it promotes transparency and accountability. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) is responsible for preparing policy instruments, such as directives and guidelines, relating to the operation of the Privacy Act and the Access to Information Act. The TBS is tasked with publishing updates in Info Source, interpreting policy, advising on updates, regularly conducting policy evaluations, and monitoring compliance. The President of the Treasury Board is responsible for overseeing the government-wide administration of the Access to Information Act.

The Treasury Board defines “Standard personal information banks” as follows:

Standard personal information banks

Personal information banks (PIBs) are descriptions of personal information under the control of a government institution that is organized and retrievable by an individual’s name or by a number, symbol or other element that identifies that individual. The personal information described in a PIB has been used, is being used or is available for an administrative purpose. The PIB describes how personal information is collected, used, disclosed, retained and/or disposed of in the administration of a government institution’s program or activity.

There are three types of PIBs: central, institution-specific and standard. The following descriptions are standard PIBs. They describes information about members of the public as well as current and former federal employees contained in records created, collected and maintained by most government institutions in support of common internal services. These include personal information relating to human resources management, travel, corporate communications and other administrative services. Standard PIBs are created by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Looking as Specific Personal Information Banks

We get a window on to the information sharing by examining various published personal information banks where this information is stored.

IRCC’s public list of personal information bank is probably the best starting point as it is laid out in a very navigable format.

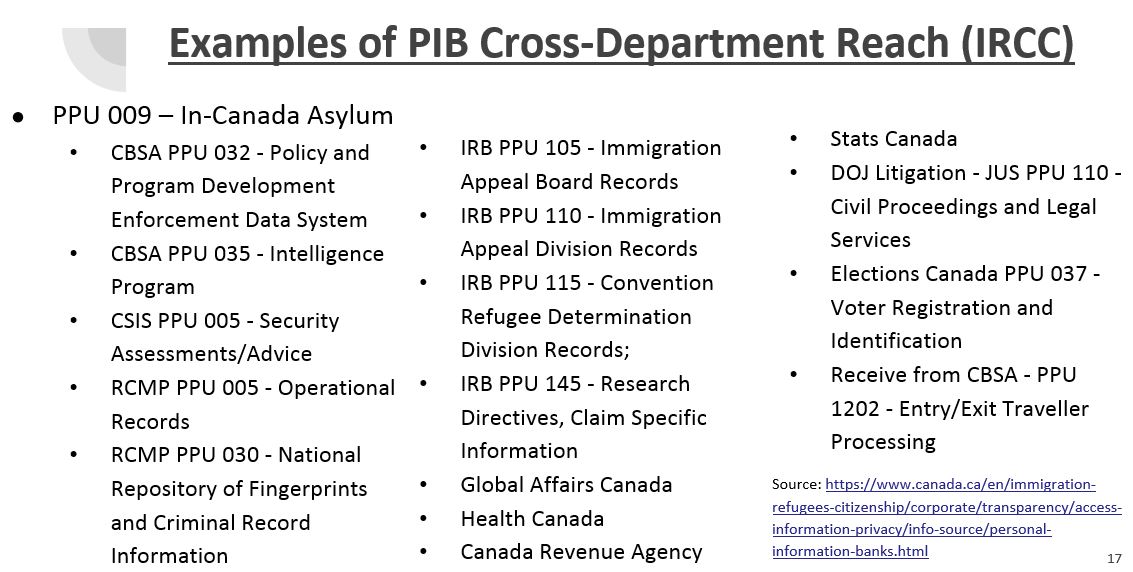

An example, and of the ones I looked at the example with the most amount of shared banks with other institutions, is for In-Canada Asylum where PPU 009 is shared with the following Government bodies through the corresponding PPUs. Again, this gives credence to our theory that privacy concerns may be heightened among certain groups.

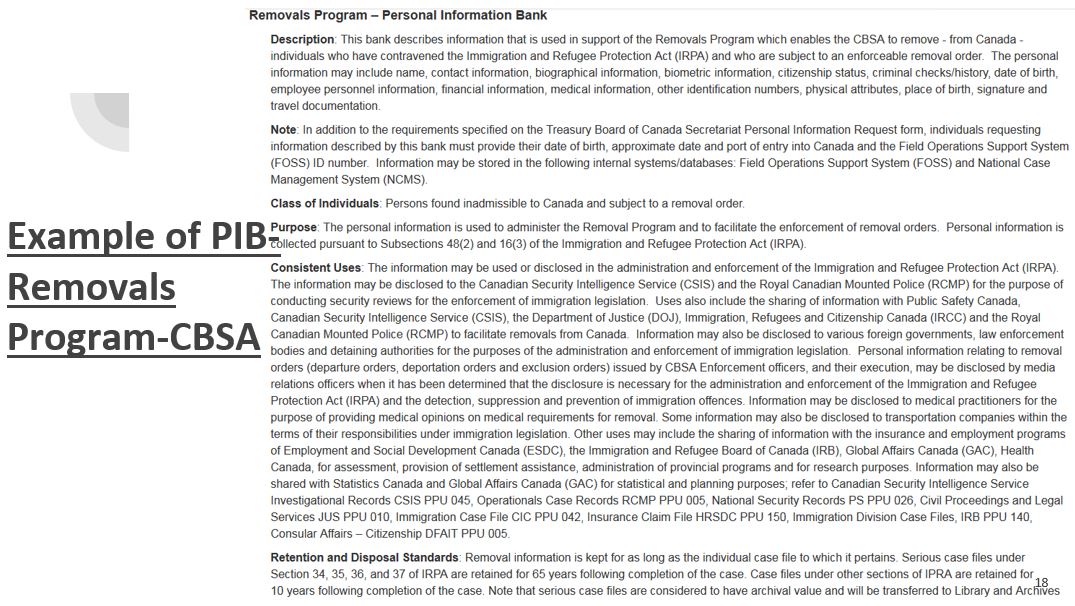

Now looking at a longer CBSA PIB on their removals program you will see information sharing under the IRPA, with CSIS, RCMP, DOJ, IRCC, Employment and Social Development Canada, IRB, Global Affairs Canada, and Health Canada. See below:

Privacy Notices and Inaccuracies

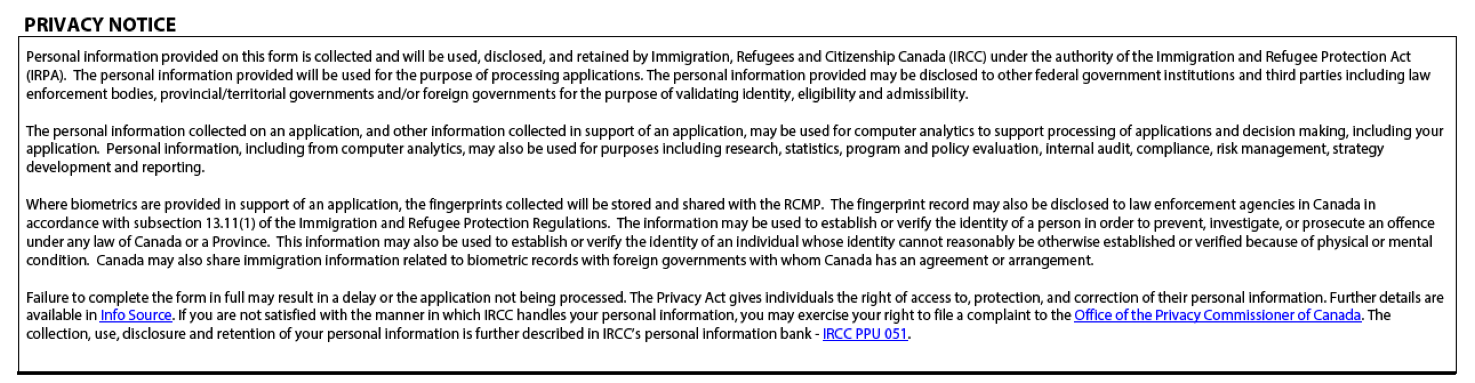

Within the immigration context, information is shared via personal information banks via the Privacy Notice

The 2017 Internal Audit of the Management of Personal Information highlighted inconsistencies between the privacy notice statements on various applications forms and the Personal Information Bank information. This appears to be an ongoing problem.

For example, IMM 5669, which is the Schedule A used for most applications, lists 3 specific personal information banks on the disclosure statement. However, 2 of those correspond to existing banks, but reflect the incorrect title for those. The third listed bank does not exist. IMM 5409, the Statutory Declaration of Common-Law Union lists in the disclosure statement 3 incorrectly named banks and 2 non-existent banks. IMM 5444, the Application for a Permanent Resident Card, lists a bank that doesn’t exist.

This also runs against 5(2) of the Privacy Act if the disclosure statements are not consistent and/or not complete when comparing it to the PIBs.

What I would suggest is that IRCC create a resource that more explicitly, clearly, and accurately confirms which forms provide information that can populate which personal information banks and what the implications of this may be. As it stands, these fine-print waivers are not serving their purposes and creating consequences unbeknownst to client and representative alike.

Retention

Each of the different PIBS list their own schedules for retaining and disposing of the information they contain.

For example, personal information that appears in the economic resident PIB has several retention schedules. Express Entry profile information is kept for 5 years. For applicants who are approved as permanent residents, the information is saved for 65 years. For inadmissible individuals, the timeline for retention is 5 years. Biometrics are saved as per the the next slide.

The CBSA will retain the personal information contained through the entry/exit traveller processing PIB for 15 years, unless there is still an ongoing investigation.

In the IRB’s Refugee Protection Division’s Records bank states that the standard paper-based case file or electronic record is maintained in the regional office for six months after the final action is taken. It is then transferred to Library and Archives Canada where it is retained for a further ten years after which it is destroyed. Cases that have archival or historical significance are retained for 50 years.

Shortcomings of PIBs?

When individuals are submitting documents, there might be information that is disclosed that doesn’t fit in the administrative purpose of the existing banks. For example, in sponsorship agreements, many applicants submit additional documents, such as joint personal banking statements that may not be related to the proof. What happens when info doesn’t fall in? That information is supposed to be destroyed by the government.

However, there is no formal guidance on how program officers should handle the additional documentation provided by applicants. As such, officers use their discretion and, in the majority of cases, officers decide to keep the information on file as additional support for their decision rather than destroy it. As a result, IRCC maintains information that has no retention and disposition schedule and that should not be maintained in accordance with the program’s PIB.

Fixing Your Personal Information

Part of the Privacy Act requirements include being able to correct personal information that is held by the Government about you.

You do so through the following link: https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/tbsf-fsct/350-11-eng.asp

IRCC did not initially have this information available on their website but kindly clarified that they have the same process which utilizes the same forms.

Dear @CitImmCanada

– I was wondering what the mechanisms are for a client to correct

incorrect personal information found in a Privacy Act/Access to

Information Request. Is there a particular form you have similar to what

CBSA offers here: https://t.co/ER7xzsPZJH

#cdnimm—

Will Tao????????|陶维 (@TheWillTruth) October

17, 2019

Hi. You’ll need to complete and submit a Record correction Request form (TBC/CTC 350-11 (Rev. 1993/02) along with copies of 2 valid pieces of ID. More information here: https://t.co/vBxPj77vcc Sorry for the delay in getting back to you on this.

— IRCC (@CitImmCanada) November 6, 2019

What Should We Do With this Information About PIBs.

This may seem overly cliche, but before I can draw some larger recommendations I need to know more and learn more as to what happens behind the curtain. I think it is not enough for Applicants to know that their information is being stored but they need to know what purposes it is being stored for and what cross-implications these can have. Doing so in a transparent way can also have the added benefit of deterring wrongdoing. Applicants who are aware that information sharing via personal information banks or otherwise through Memorandum of Understandings (MOUs), legislative provisions, or inter-governmental agreements would be more likely to pause before rushing through an immigration form or engaging professionals to do different aspects without coordinating (the Tax Accountant vs. the Immigration Rep is a classic example).

I think the current treasure hunt that is piecing together PIBs and tracing the information sharing should be replaced with greater education and greater assurances that this information will be protected.

In 2015, along with my colleague Krisha Dhaliwal and Jason Shabestari, we wrote a piece called “It May Be Too Late to Repent: Immigration, Tax, and Privacy Concerns in the Context of New Proposed Changes to Social Insurance (SIN) Number Sharing”, Canada’s Immigration and Citizenship Bulletin (June 2015) after SIN-Sharing was introduced to IRCC.

Just recently, we’re seeing some of these concerns come to fruition to Canadians who have been victims of SIN fraud. See: Cornwall, Ont., woman loses life savings to terrifying ‘SIN scam’

The consequence of ‘not knowing’ or ‘not being able to confirm’ where privacy breaches have occurred and what usage/sharing/collection of personal information is justified is a greater likelihood of privacy breaches, of the sort that IRCC is not immune too [see: Privacy Act, Access to Information Act, Annual Report 2017-2018 (PDF, 1 MB) which documents 7 material breaches which occurred between 2017-2018].

In this age of data mining, information sharing, and the use of information for artificial and other intelligence, IRCC must ensure that immigrants, by virtue of their status and their interactions with Government, are not left in the dark on issues of privacy rights and protection of their personal information.