In the recent Federal Court decision of Hassani v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 FC 734, Justice Gascon writes a paragraph that I thought would be an excellent starting point for a blog. Not only does it capture the state of administrative decision-making in immigration and highlight some of the foundational pieces, but also I want to focus on one part of it that I may respectfully suggest, needs a re-think.

Hassani involved an Iranian international student who was refused a study permit to attend a Professional Photography program at Langara College. She was refused on two factors – [1] that she did not have significant family ties outside Canada and that [2] her purpose of visit was not consistent with a temporary stay given the details she had provided in her application. On the facts, it is definitely questionable that this case even went to hearing given the Applicant had no family ties in Canada and all her family ties were indeed outside Canada and in Iran. Nevertheless, Justice Gascon did a very good job analyzing the flaws within the Officer’s two findings.

There is one paragraph, 26, that is worth breaking down further – and there’s one foundational principle cited that I think needs a major rethink.

Justice Gascon writes:

[26] I do not dispute that a decision maker is generally not required to make an explicit finding on each constituent element of an issue when reaching its final decision. I also accept that a decision maker is presumed to have weighed and considered all the evidence presented to him or her unless the contrary is shown (Florea v Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration), [1993] FCJ No 598 (FCA) (QL) at para 1). I further agree that failure to mention a particular piece of evidence in a decision does not mean that it was ignored and does not constitute an error (Cepeda-Gutierrez v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 1998 CanLII 8667 (FC), [1998] FCJ No 1425 (QL) [Cepeda-Gutierrez] at paras 16–17). Nevertheless, it is also well established that a decision maker should not overlook contradictory evidence. This is particularly true with respect to key elements relied upon by the decision maker to reach its conclusion. When an administrative tribunal is silent on evidence clearly pointing to an opposite conclusion and squarely contradicting its findings of fact, the Court may intervene and infer that the tribunal ignored the contradictory evidence when making its decision (Ozdemir v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2001 FCA 331 at paras 9–10; Cepeda-Gutierrez at para 17). The failure to consider specific evidence must be viewed in context, and it will lead to a decision being overturned when the non-mentioned evidence is critical, contradicts the tribunal’s conclusion and the reviewing court determines that its omission means that the tribunal disregarded the material before it (Penez at paras 24–25). This is precisely the case here with respect to Ms. Hassani’s family ties in Iran. (emphasis added)

What is the Florea Presumption?

As stated by Justice Gascon, the principle in Florea v Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration),[1993] FCJ No 598 (FCA) pertains to a Tribunal’s weighing of evidence and the presumption that they have considered all the evidence before them. It puts the onus on the Applicant stating otherwise, to establish the contrary.

As the Immigration and Refugee Board Legal Services chapter on Weighing Evidence states:

Rather, the panel is presumed on judicial review to have weighed and considered all of the evidence before it, unless the contrary is established. (see: https://irb.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/legal-concepts/Documents/Evid%20Full_e-2020-FINAL.pdf)

This case and principle is often cited in refugee, humanitarian and compassionate grounds matters, inadmissibility cases, and IRB matters.

Reviewing case law for the last two years (since 2021), I did find a handful of the thirty-cases I reviewed that did engage this case and principle in a temporary resident context.

See e.g. study permit JR – Marcelin v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 2021 FC 761 – Madam Justice Roussel at para 16 [JR dismissed]; PNP Work Permit – Shang v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2021 FC 633 at para 65 citing Basanti v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2019 FC 1068 at para 24 – Madam Justice Kane [JR allowed]; Minor Child TRV Refusal – Dardari v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 2021 FC 493 at para 39 – adding the portion – and is not obliged to refer to each piece of evidence submitted by the applicant – Madam Justice St-Louis [JR dismissed];

Related to this is the long-standing and oft-cited decision of Cepeda-Gutierrez v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) 1998 FC No 1425 in which Justice Evans re-iterated that an Agency stating they considered all evidence before it (even as a boilerplate statement) would usually be enough to suffice and assure parties and the Court of this. He writes:

[16] On the other hand, the reasons given by administrative agencies are not to be read hypercritically by a court (Medina v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) (1990), 12 Imm. L.R. (2d) 33 (F.C.A.)), nor are agencies required to refer to every piece of evidence that they received that is contrary to their finding, and to explain how they dealt with it (see, for example, Hassan v. Canada (Minister of Employment and Immigration) (1992), 147 N.R. 317 (F.C.A.). That would be far too onerous a burden to impose upon administrative decision-makers who may be struggling with a heavy case-load and inadequate resources. A statement by the agency in its reasons for decision that, in making its findings, it considered all the evidence before it, will often suffice to assure the parties, and a reviewing court, that the agency directed itself to the totality of the evidence when making its findings of fact.

(emphasis added)

Why the Florea Presumption Should Be Reversed For Temporary Resident Applications and Any Decision Utilizing Advanced Analytics/AI/Chinook/Cumulus/Harvester

My argument is that this presumption that all evidence has been considered, as well as the boilerplate template language stating that it was considered, should not apply universally in 2023.

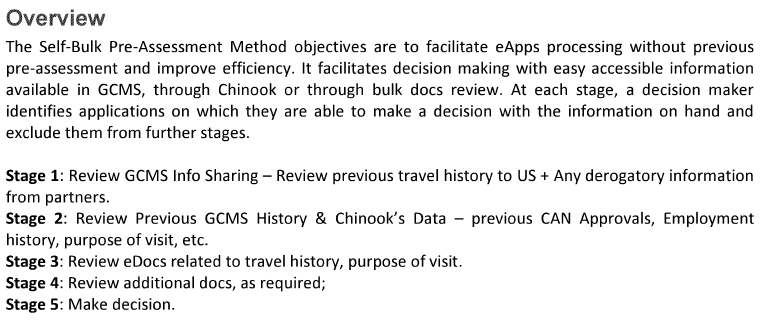

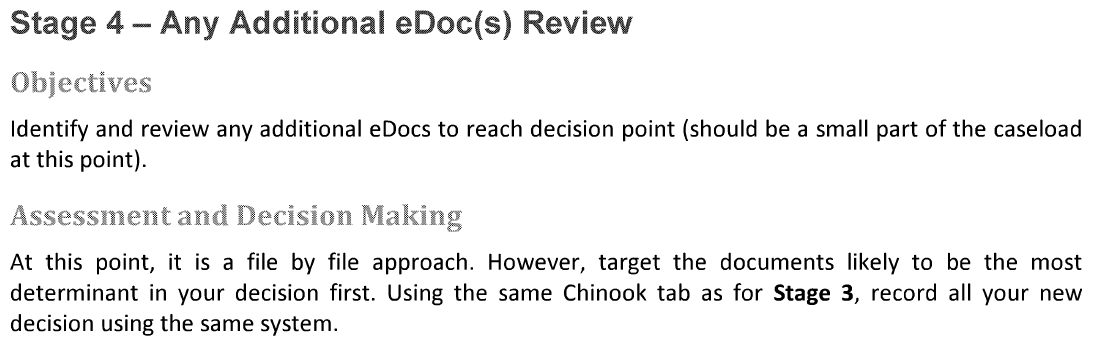

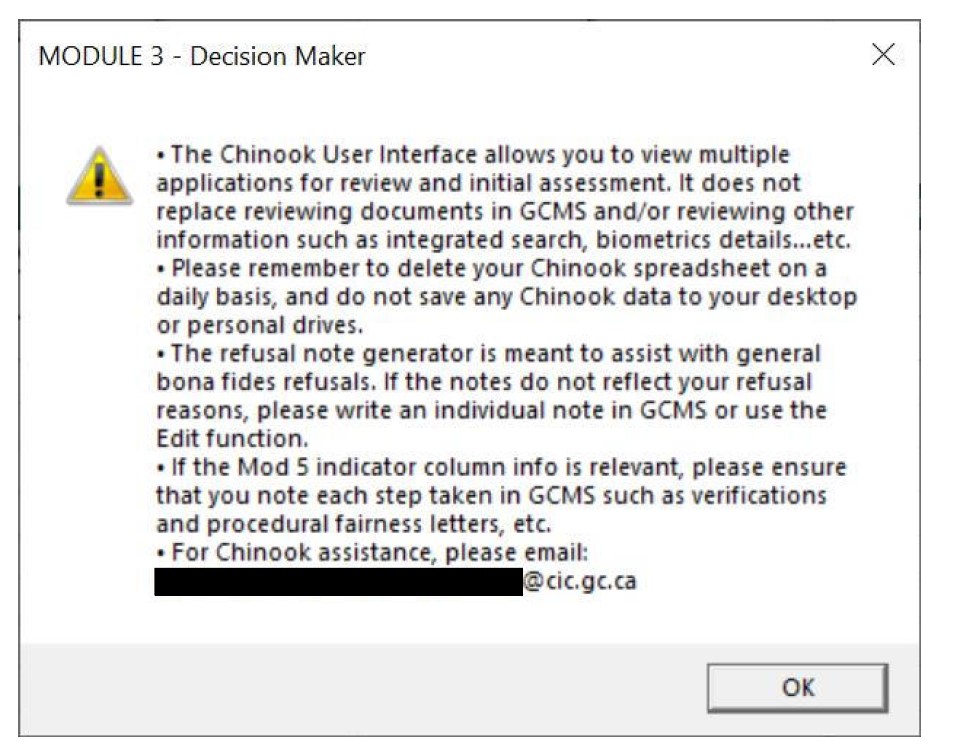

We know enough (again not enough about the system writ large) but enough to know that systems such as Chinook were created to facilitate the processing of temporary resident applications in hundreds of seconds, to extract data into excel tables for bulk processing, and to automate eligibility approvals. These were done specifically allow Officers to spend less time and consider enough, not all, of the evidence before them to render a decision.

I think the fact that applications are being auto-approved for eligibility, simply on a set of rules that are inputted primarily based on biometric information of an applicant should be enough to raise concerns that the systems even require consideration of most of the evidence submitted by an applicant.

All the materials on bulk processing that IRCC has released in the past few years, has been focused on the fact that not all documents need to be reviewed (not wording that states: review Additional Documents, as required).

If you look at the Daponte Affidavit and the original Module 3 Prompt that was created, it does not add confidence to the requirement that all documents needed to necessarily be reviewed:

We learned that in response to concerns, they added to Chinook a prompt reminder for Officers to review all materials, but it is clear Chinook has gone far beyond ‘review and initial assessment’ to bulk processing.

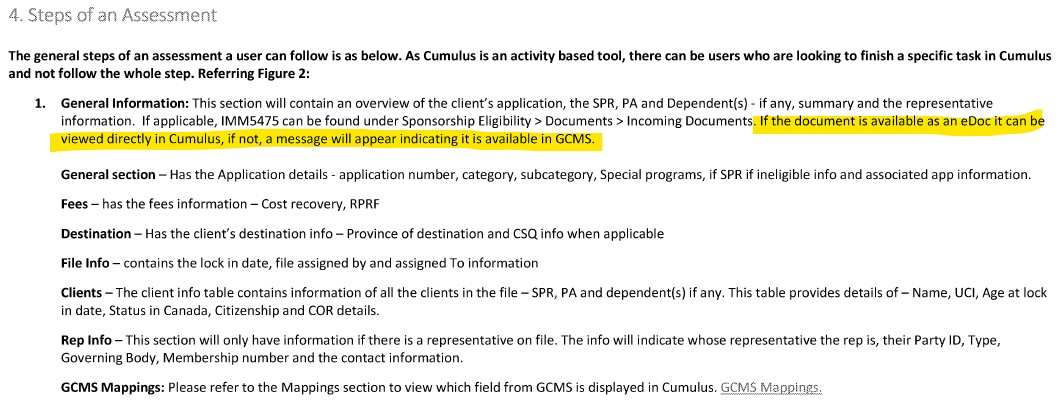

Even with Cumulus, it is clear that if some docs that are not coverted to e-Docs they have to be pulled up separately in GCMS, the very tedious process that tools such as Cumulus seek to avoid.

I would presume that it would be much easier for an Officer to make decision based on these summary extractions then to go into the documents.

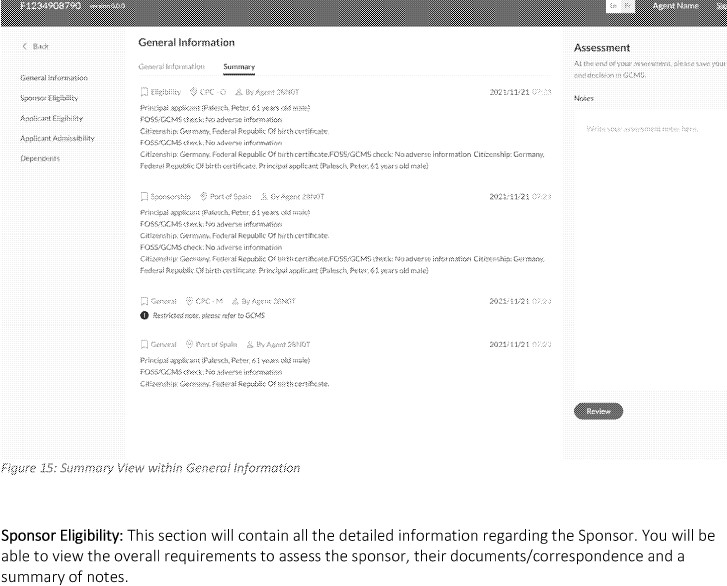

The documents are viewed below, much more akin to a ‘preview’ mode.

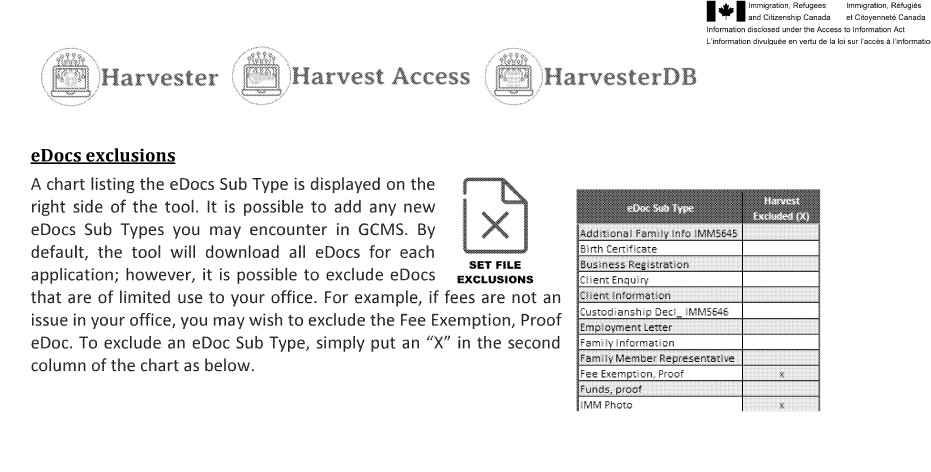

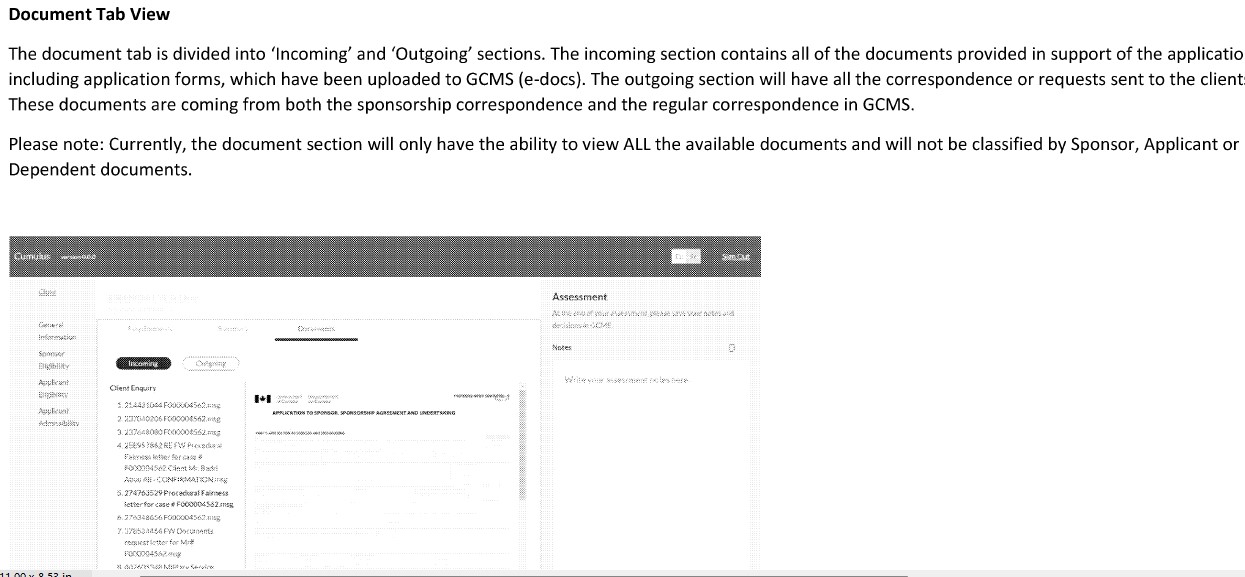

Harvester, a tool that facilitates the conversion of documents into a reviewable format is similarly based on what documents can be extracted.

Based on the way it is described and how some offices can exclude certain documents, it already suggests not all documents make it to the purview of the Officer.

Most importantly, as a constraint is time. As Andrew Koltun has uncovered, IRCC spends 101 seconds on average, with Chinook processing. https://theijf.org/nearly-40-per-cent-of-student-visa-applications-from-india-rejected-for-vague-reasons#

Respectfully, 101 seconds cannot be enough to consider but one or two documents – max – before rendering a decision. The future use of Large-Language Models and OCR to extract key terminology from the applications and eventually respond to it, entirely changes the future landscape.

While the ‘increasing demands’ and ‘backlog’ argument will continue to be utilized by IRCC, I suggest that IRCC’s implementation of AI via advanced analytics has been aimed at expediting bulk decision-making. The Courts should be wary of arguments of backlogs, when those same systems have expedited files (with limited/no review of eligibility) in ways that were not previously available.

Way Forward – Acknowledging Officers Are Reviewing Summaries and Relying on ‘Other Sources/Primarily Data’ to Render Decisions

I think perhaps the better way forward, rather reversing the onus, is to acknowledge publicly that application materials are not being considered in their totality and that what is submitted is only one portion of the data the Applicant submits.

Perhaps this requires amending IRPA/IRPR at Part 4.1 and through R.186.3 (1) create Regulations or as suggested by the Directive on Automated Decision Making to publish meaningful explanations to what was considered in an application (especially if and how AA was used on a case [likely without going into the specific secret algorithms]).

However, I do not see that as likely. The reality is there are different sets of documentation and criteria considered for different applicants. Each Visa Officer has Officer Rules to pull files out of the automation/template Chinook queue, and the request for and consideration of these documents allows for refusals to ultimately be rendered with a factual basis. To put it more simply, the Florea presumption that the Officer considered all submissions and materials avoids IRCC from having to parse out the potential inequities of the submissions and materials reviewed and required for each applicant.

Still, I think the Federal Court should look carefully at whether Florea still applies in the modern day context of automated, bulk, triaged, and time-sensitive decision-making.