No, Harry and Meghan I won’t take your case pro bono – but here’s a proposition and some background

I think I found a semi-decent plan for Harry and Meghan to immigrate to Canada:

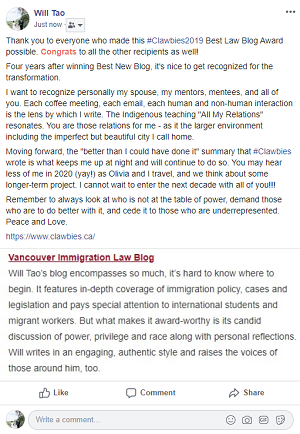

Award-Winning Canadian Immigration and Refugee Law and Commentary Blog

I think I found a semi-decent plan for Harry and Meghan to immigrate to Canada:

I am a huge lists fan. I also have a very short memory span so writing things is literally my way of carrying forward 2018

I have decided I want to write a longer (more substantive piece) about where I see Canadian immigration 1, 5, and 10 years

We spend so much time focusing on the now and the how that we forget to look

Many of you may already know or have recently heard that I found a new home for providing legal services and mentorship.

As many of you know, Vancouver Immigration Blog likes to highlight the experiences and perspectives of other migrants and migrant-supporting organizations/individuals.

A portion of this article is a modified summary of a presentation done in October 2019

Will Tao is an Award-Winning Canadian Immigration and Refugee Lawyer, Writer, and Policy Advisor based in Vancouver. Vancouver Immigration Blog is a public legal resource and social commentary.

he/his/him

Acknowledges that he lives and works on the traditional, unceded territories of the Coast Salish peoples – sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) nations.

This site reflects my personal opinions and views only and should not be relied on and should be verified prior to any professional use. Please note that none of the information on this website should be construed as being legal advice. As well, you should not rely on any of the information contained in this website when determining whether and how to apply to a given program. Canadian immigration law is constantly changing, and the information above may be outdated. If you have a question about the contents of this blog, or any question about Canadian immigration law, please contact the Author.