Her Steps – A Poem

The structured systems that serve to silence our sisters in their seven point five and subsume them with stress in their remaining seven.

Award-Winning Canadian Immigration and Refugee Law and Commentary Blog

The structured systems that serve to silence our sisters in their seven point five and subsume them with stress in their remaining seven.

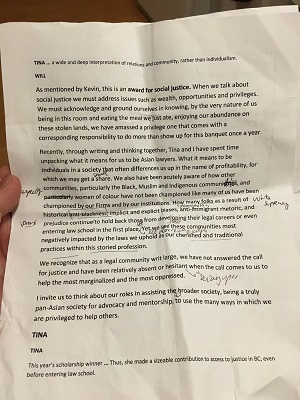

Reflecting on My FACLBC Intro Speech – Two Days Later I am writing two days after delivering a speech at the FACLBC Gala that raised

Since January of this year, IRCC has now provided instructions that allow for authorized leave periods of up to 150-days contingent on school approval.

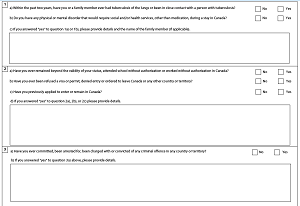

Recently in Sbayti v. Canada (MCI), 2019 FC 1296, Justice Pamel (a recent appointee to the Federal Court earlier this year) had a bit of

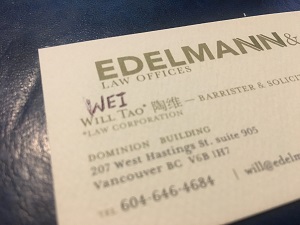

My name is Will Tao. My Chinese name is Tao Wei. I wrote a post recently where I talked about being named after Victoria where

“It’s Not What They Call You, It’s What You Answer To” – ascribed to comedian W.C. Fields (but I received this teaching through an April

“Our lives have no meaning, no depth without the white gaze. And I have spent my entire writing life trying to make sure that the

Will Tao is an Award-Winning Canadian Immigration and Refugee Lawyer, Writer, and Policy Advisor based in Vancouver. Vancouver Immigration Blog is a public legal resource and social commentary.

he/his/him

Acknowledges that he lives and works on the traditional, unceded territories of the Coast Salish peoples – sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) nations.

This site reflects my personal opinions and views only and should not be relied on and should be verified prior to any professional use. Please note that none of the information on this website should be construed as being legal advice. As well, you should not rely on any of the information contained in this website when determining whether and how to apply to a given program. Canadian immigration law is constantly changing, and the information above may be outdated. If you have a question about the contents of this blog, or any question about Canadian immigration law, please contact the Author.